- Home

- David Hewson

The Garden of Evil Page 4

The Garden of Evil Read online

Page 4

“There was a loose flagstone beneath the window,” one of the officers replied. “We just looked. These are just a few. There must be fifty or more in there.”

“Keep looking,” Falcone ordered, then took the photos and spread them out on a dusty chair.

Costa stared at the images on the flimsy homemade prints. It was clear that they had been taken in this very room. There was the same stone floor. In places he could see splashes of paint, and even a pot and a brush. In one photograph there was the corner of the green drape used for the canvas they’d uncovered too.

There was the link. Every photo portrayed the head and torso of a naked woman. Most of them looked foreign. Some were black, with the overblown hair and excessive makeup of the African hookers who worked the suburbs.

It was impossible to judge the expressions on their faces. It could have been rapture, sexual or spiritual. Or pain in the final moments of life.

He turned to Peroni.

“Do you know any of them, Gianni?” Costa asked.

“What the hell is that supposed to mean?” Peroni roared.

Costa cursed his own stupidity. The big man had once been one of the most effective officers working the illicit sex scene in Rome. His career had collapsed because once—just once—he’d slept with a vice girl himself.

“I’m sorry. I phrased that very badly. You worked vice for many years, and very well indeed,” Costa explained patiently. “I think these women look like hookers. But if you thought so, too, it would mean a lot more.”

Peroni sighed, then shrugged apologetically. “They look like hookers.” He glanced back at the corpse of the Frenchwoman, now surrounded by attendants making the body bag ready. “She doesn’t, though. She . . .”

Peroni stared at the photos again. Then he picked one up in his gloved hand.

It was a muscular black woman with a head of long hair, artificially straightened and glossy. She seemed to be trying very hard to look as if she were in the throes of ecstasy. All the women in the photographs did.

“I’ve booked her,” Peroni said. “Nigerian. Quite a nice kid.” He stared out of the grimy window for a moment. Then he spoke again. “She’s on the missing persons list. Has been for a few weeks. I saw it on the board. I recognised . . .”

Falcone was cursing under his breath again, and this time Costa was sure there was something specific behind his reaction.

Then, before he could ask, there was a brief pained scream from the team raising the flagstones. Costa looked at the men. They were standing back from the area on which they’d been working. The blood had drained from their faces. One of them looked ready to throw up.

Falcone was there first, even with the limp. He took one look at what was emerging from beneath the damp, algaed stone.

“Doctor,” he said, just loudly enough to bring Teresa Lupo to his side. Costa and Peroni moved forward to look. Then the big man swore and walked away.

Something wrapped tightly in semitransparent plastic, like a gigantic artificial cocoon, was emerging from the grey, damp earth beneath the solid floor of the studio. Costa glanced at it and started to walk, rapidly, around the room. There were several areas where the grey flagstones appeared to have been moved recently, sometimes hidden by paint pots, sometimes by empty easels or furniture.

When he got back to Falcone, Teresa Lupo was hovering over the discovery with a scalpel in her hand.

“I don’t think this will be pretty, I’m afraid,” she said firmly. “Those of a delicate nature should leave now.”

Costa stayed and watched. He and Falcone were the only police officers who did. The face beneath the plastic was grey and dirty and, in spite of the substantial period that must have passed since she was killed, undoubtedly that of the Nigerian woman Peroni had recognised. The stench that rose the moment Teresa made the incision would, he thought, live with him for a long time.

“I don’t think she’s alone,” Costa said, catching Falcone’s eye, realising, to his dismay, that the old inspector did not, for some reason, appear to be surprised. “We have to—”

There was a sound from outside. Not in the alley, somewhere else. Costa glanced behind the painting. There was a dusty door there, beyond an ancient dining table covered in paint stains, half hidden behind some old sackcloth drapes. It was ajar.

“He’s still here,” Costa muttered, then leapt the table and headed for whatever lay beyond, out in the cold grey day.

Two

IT WAS A COURTYARD OF A KIND, A MESSY PLACE OF JUNK: old wooden cases, discarded furniture, a couple of tall metal filing cabinets rusting to nothing on the green cobblestones. A man could easily hide here. A single narrow corridor, dank with moss and decay, led off from the far corner, inwards, through the heart of whatever greater building—the Palazzo Malaspina, Costa’s memory wanted to tell him—sprawled across this hidden enclave of the city, then, he assumed, onto the street. And freedom.

Falcone was barking orders into his radio, demanding immediate action from the officers outside in the vicolo. Costa wanted to tell him this narrow malodorous alley didn’t run that way. It burrowed deep into the labyrinthine palace itself. Stumbling out into the grey daylight of the yard, he could hear the crush of bodies behind him, Peroni’s voice in the lead, above the tense chatter of men working themselves into the state of mind that went with a pursuit.

Costa stopped and took his bearings, thinking. Why would a murderer wait so close to the scene?

Some did. Some couldn’t resist it.

One of the officers who’d found the buried corpse appeared at his side. With the automatic instinct that seemed to come with the job for some, he’d taken out his gun and was now holding it in front, uncertainly, wavering between the high filing cabinets, an obvious place for someone to hide, and a pile of old furniture near the wall.

Costa pushed down the barrel of the weapon. “No guns,” he insisted. “It could just be a kid.”

And that was a stupid thing to say, he thought. Kids wouldn’t mess around places like this. It was all too dark and dank and scary, particularly if you peeked in the windows and saw what was going on inside, beneath the placid gaze of that naked woman on the canvas.

The grimy yard was at least ten metres on each side, and half of it crammed with junk, some of it looking as if it had been thrown there years ago. The surrounding building rose six storeys high, past grimy barred windows, a line of scarred black brick leading to the leaden December sky, filled, at that moment, by a flock of swirling starlings.

Costa looked up. He didn’t see a single face at any of the rainstreaked panes of near-opaque glass in the storeys above. Then he stared down the long narrow corridor leading to God knew what. It was empty, and towards the end turned into a tunnel, a pool of darkness formed by the overhanging building above. A tiny square of dim daylight was just visible at the end. There wasn’t time for a man to escape them so quickly, surely. Nor could he have got there without making a sound.

“Assume he’s here,” he told the officer quietly. “We’ll go through the junk piece by piece until we find something or he moves. Assume—”

There was a voice. Peroni was bellowing. Behind a rotting wooden desk, its metal legs like skeletal limbs made of rust, was the shadow of a figure, crouching, only the shoulders, torso, and legs visible.

Something struck Costa the moment he saw it. The man wasn’t trembling. He was as still and calm as a statue.

* * *

“YOU HAVE TO COME OUT OF THERE,” COSTA SAID CALMLY, walking forward, signalling to the officer with the revolver to keep it trained down towards the stones just in case.

“Sovrintendente!” Falcone yelled.

Costa ignored him and continued walking forward. “You need to come out now, sir.” He spoke in a voice he hoped was low on threat but brooked no argument. “This is a crime scene and we have to talk to you.”

The figure was no more than three or four strides away. He didn’t move.

“Start movi

ng!” Peroni bellowed.

Costa glanced back at the men behind him. Falcone was silent now. It wasn’t like the old inspector.

“Out!” Peroni roared, and that did it. The long dark form—the intruder was dressed in dark khaki, some kind of military-style top and trousers, with black boots tied tight around the ankle, just like a soldier—was starting to move.

“Stand by the wall,” Costa ordered. “Hands above you. This is just a routine matter. Just a . . .”

He didn’t go on. The figure had worked its way free, with an agile athleticism that gave Costa pause for thought. He still couldn’t see a face. Just a long, lithe body, muscular and fit, at ease in the anonymous military clothing.

“Dammit!” Falcone shouted, pushing his way through the crowd of officers jamming the free space in the courtyard. “This is my investigation, Costa. You do what I tell you.”

“Sir . . .” he said, and watched the figure in khaki emerge from behind the rotting carcass of a mattress, pink and grey stripes hanging down in ragged tatters from the burst mouldy body.

The man wore a black full-face gas mask with a glass eye shield that revealed nothing at all. He had a repeating shotgun in his right hand, held tight with a professional deliberation, and, in his left, some kind of canister that was already beginning to smoke at the handle.

“Weapons!” Falcone cried.

Costa wasn’t really listening. Sometimes these things came too late. The smoking canister was already spinning in their direction, turning in the air, releasing a curling line of pale fumes that carried before it the noxious smell Costa knew from the last riot he’d had the privilege to attend.

The thing burst with a soft explosion, and a dense white cloud instantly enveloped them. Coughing, eyes streaming, he instinctively stumbled clear, down towards where he expected the exit corridor to be, eyes tight shut, a handkerchief clutched across his mouth and nose.

Gasping for clean air, aware of the curses and screeches of the men behind him, trapped in the noxious fumes, Costa was sure of one thing: Falcone would haul him over the coals for the way he had handled this particular encounter. Perhaps with good cause.

Then, as he half knelt, half fell against the grubby courtyard wall, something brushed his shoulder.

He looked up. The khaki figure was standing there, still in his mask, which hid, Costa guessed, a broad, self-satisfied smile.

The shotgun was pointed directly into Costa’s face, the barrel no more than a hand’s length away.

Costa coughed, tried to look the man in the eye, and said, “You’re under arrest.”

Then he watched, feeling a little baffled and not, for a single moment, frightened.

Nothing happened. Costa looked again. Somehow the fabric of his would-be killer’s military gloves had gotten tangled in the gap between the trigger and the metal guard, preventing the firing of the weapon through nothing more than a shred of fabric and luck. It was a small and temporary thing to keep a man alive, but Costa wasn’t much minded to think on it. Instead, he kicked out hard with his right leg and hit the gunman painfully on the shin. The shotgun tilted up towards the sky and fired, with an explosive screech that re-bounded round the black brick and sprayed hot pellets through the air. A soft lead rain dappled the ground around Costa.

Then the gas returned, and this time it was in his eyes, stinging like wounds from a million crazed bees, sending tears streaming down his cheeks, bile surging in his throat.

Costa swore. Behind him men were screaming. He rolled out of the drifting smoke haze and saw the brown-clad figure disappearing down the corridor, into the dark pool of shadow, towards the grey patch of light at the end.

With an aching reluctance, he lurched down the slippery cobblestones, coughing, choking, realising there was no one from the team behind in much of a state to help him.

The memory of the shotgun barrel poking in his face burned as badly as the tear gas. He took one more look down the alley. Whoever it was had got a good head start on them all.

Costa watched as the military form emerged from the shadows and fell into the bright light at the distant wall, then stopped, turned, ripped off the gas mask, hitched the shotgun up to his shoulder, and stared back at him.

He wore a black military hood beneath, the kind the antiterrorist people wore, tight black cotton with two tiny slits for eyeholes. It was too far to take a worthwhile shot from this distance. The man was, surely, making some kind of point.

Costa watched as the hood contorted around the mouth, the lips closed, then formed a perfect O, and those distant hands closed round the trigger.

Somehow he could hear the single word the figure was mouthing, even though that was impossible.

Boom, the man said, and then laughed.

What happened next came so naturally Costa didn’t even have to think about it. He ripped the service pistol out of his shoulder holster, took some vague aim down the brick corridor ahead, and let loose four rounds in rapid succession.

The figure in khaki had fallen back against the wall, twitching and shrieking in a way that Costa, against his own instincts, found satisfying.

But it wasn’t a wound. It was shock and fear and some kind of outrage that he should be a target in the first place. The man hauled himself to his feet and dashed a vicious glance back down the alley before he stumbled to the right and out of sight. But at least the brief moment of fear Costa had instilled in him redressed the balance a little.

Without waiting to see what condition the others were in, he dashed towards the brick tunnel ahead, lurching like a sick man, holding the weapon loose and impotent by his side, dimly aware he had only a couple of rounds left in it now, against a furious, murderous individual with a repeating shotgun who was surely about to try to bury himself inside the heart of Rome on a busy holiday afternoon.

There was no time to radio for assistance. He wasn’t sure he had the voice to make the call anyway. All Costa could do was run, and, with the old skills he still retained from his marathon days, he found that rhythm almost instantly.

When he emerged from the cold black overhang of the building at the end of the passageway, he blinked at the sunlight, and the location. He was now just round the corner from the Piazza Borghese. As he squinted his stinging eyes against the sudden sun, he saw a khaki figure limping towards the square.

Inside his jacket his phone was ringing. He recognised the special tone. It was Emily calling. She’d have to wait.

Three

THE RAIN HAD LEFT THE COBBLESTONES OF THE PIAZZA Borghese greasy and black. This was one of the few open spaces between the Corso and the river. Every day hundreds came here to park, strewing vehicles everywhere: cars and vans, motorbikes and scooters. Students from the nearby colleges were gathered in one corner, arms full of books and work folders, laughing, getting ready for lunch. Costa couldn’t see anyone of interest, no athletic, brownclad figure with a shotgun anywhere. Just a few shoppers and office workers walking the damp pavement.

Costa scanned the square, wondering where a fugitive might run in this part of Rome. There were so many places. South towards the Pantheon and the Piazza Navona was a labyrinth of alleys that could hide a hundred fleeing killers. West lay the bridge over the river, the Ponte Cavour, and escape into the plain business streets beyond the Palace of Justice. And both north and east . . . street after street of shops, apartment blocks, and anonymous offices. He didn’t know where to begin.

Backup would arrive soon. The officers from the studio, Gianni Peroni, a furious Falcone.

Costa took one last good look around him and sighed. Then the phone rang again. That familiar tone again. This time he answered it.

“May I take it you’re hunting for a gentleman wearing a Rambo outfit, a very suspicious-looking expression, and trying, rather poorly, to hide the fact he’s got a rifle or something on his person?” she asked.

Once an FBI agent, always an FBI agent.

“Just tell me where,” Costa ordered his wife qu

ietly, grimly.

“I’ve followed him to the Mausoleum of Augustus. I could be wrong but I think he may be headed down into it. Good place to hide, among all those bums.”

Costa knew the monument, though not well. Roman emperors got mixed deals when it came to their heritage. Hadrian’s mausoleum turned into the Castel Sant’Angelo. Augustus, one of the most powerful emperors Rome had ever known, came off much worse. Over the centuries, his burial site had been everything from a pleasure garden to an opera house. Now, after Mussolini laid waste to it in preparation for his own tomb, one he never came to occupy, it was a sad wreck of stone set in its own rough green moat of grass, half hidden between the 1930s Fascist offices set behind the Corso and the high embankment by the Tiber. The scrubby city grass was a favourite sleeping place for local tramps. The interior was a warren of dank, crumbling tunnels. It was so unsafe the public had been barred years ago.

“Thanks,” he told Emily. “Now go get a coffee. Somewhere a long way from here.”

He didn’t wait for an answer. He started running north, towards the river. There was construction work everywhere. The authorities were creating a new home for the Ara Pacis, the Altar of Peace, one of the great legacies of Augustus, and a sight that had been withheld from Rome and the world for too long. But for now the area was a mess of cranes and closed roads, angry traffic and baffled pedestrians wondering where the pavement had gone.

He rounded a vast hoarding advertising the new Ara Pacis building and found himself facing the southern side of the mausoleum, with its locked entrance and steps leading down to the interior. It looked more dismal and decrepit than he remembered: a rotting circle of once golden stone falling into stumps at the summit, crowned by grass and weeds and ragged shrubbery. A couple of tourists hovered near the padlocked gate, wondering whether to take photos. Beyond the railing, Costa could see a bunch of itinerants huddled around the familiar objects that went with homeless life in the city: bottles of wine, mounds of old clothing, and a vast collection of supermarket bags bulging with belongings.

The Garden of Angels

The Garden of Angels Solstice

Solstice Death in Seville

Death in Seville A Season for the Dead

A Season for the Dead The Killing tk-1

The Killing tk-1 The Savage Shore

The Savage Shore Dante's Numbers

Dante's Numbers Sacred Cut

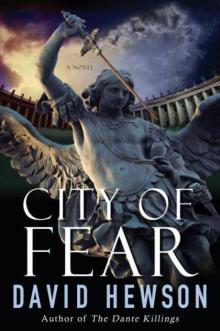

Sacred Cut City of Fear nc-8

City of Fear nc-8 The Blue Demon

The Blue Demon The Garden of Evil

The Garden of Evil The Lizard's Bite

The Lizard's Bite The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Sleep Baby Sleep

Sleep Baby Sleep Lucifer's Shadow

Lucifer's Shadow Season for the Dead

Season for the Dead The Seventh Sacrament

The Seventh Sacrament The Garden of Evil nc-6

The Garden of Evil nc-6 Juliet & Romeo

Juliet & Romeo A Season for the Dead nc-1

A Season for the Dead nc-1 The Fallen Angel nc-9

The Fallen Angel nc-9 Little Sister

Little Sister The Lizard's Bite nc-4

The Lizard's Bite nc-4 The Killing 2

The Killing 2 The Fallen Angel

The Fallen Angel The Sacred Cut

The Sacred Cut Carnival for the Dead

Carnival for the Dead The Villa of Mysteries nc-2

The Villa of Mysteries nc-2 Macbeth

Macbeth The Killing - 01 - The Killing

The Killing - 01 - The Killing The Villa of Mysteries

The Villa of Mysteries Dante's Numbers nc-7

Dante's Numbers nc-7 The Sacred Cut nc-3

The Sacred Cut nc-3 The Seventh Sacrament nc-5

The Seventh Sacrament nc-5