- Home

- David Hewson

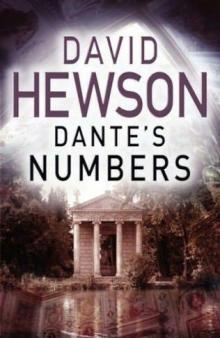

Dante's Numbers

Dante's Numbers Read online

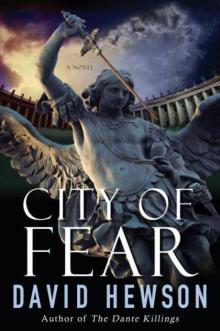

ALSO BY DAVID HEWSON

THE NIC COSTA SERIES

A Season for the Dead

The Villa of Mysteries

The Sacred Cut

The Lizard's Bite

The Seventh Sacrament

The Garden of Evil

AND

Lucfer's Shadow

Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself within a forest dark,

For the straightforward pathway had been lost.

—The Divine Comedy, Inferno, Canto I. Dante Alighieri,

translated by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

ALLAN PRIME PEERED AT THE WOMAN THEY'D SENT from the studio, pinched his cheeks between finger and thumb the way he always did before makeup, then grumbled, “Run that past me again, will you?”

He couldn't figure out whether she was Italian or not. Or how old, since most of her face was hidden behind a pair of large black plastic-rimmed sunglasses. Even—and this was something Prime normally got out of the way before anything else— whether she was pretty. He'd never seen this one at Cinecittà, and a part of him said he would have noticed, if only in order to ask himself the question: Should I?

She looked late twenties, a little nervous, in awe of him maybe. But she was dressed so much older, in a severe grey jacket with matching slacks and a prim white shirt, its soft crinkly collar high up on her neck. It was a look out of the movies, he decided. Old movies from back when it was still a crime to be skinny and anything less than elegant. Particularly her hair, a platinum blonde, dyed undoubtedly, pinned behind her taut, stiffly held head in a ponytail that, as she walked into the living room of his apartment, he'd noticed was curled into a tight apostrophe.

It was an effect he found strangely alluring until the connection came to him. Unsmiling, eyes hidden behind heavy shades that kept out the burning July morning, Miss Valdes—although the Spanish name didn't fit at all—resembled one of those cool, aloof women he'd watched in the downtown theatres when he was a kid in New York, rapt before the silver screen. Like a cross between Kim Novak and Grace Kelly, the two full-bodied celluloid blondes he'd first fallen hotly in love with as he squirmed with adolescent lust in the shiny, sticky seats of Manhattan flea pits. He hadn't encountered silent, fixated women like this in the business in three or four decades. The breed was extinct. Real bodies had given way to rake-thin models, exquisite coiffures to impromptu mussed-up messes. The species had moved on, and now he knew what kind of job it did these days.

It made death masks of people. Living people, in his case.

“Signor Harvey say…” she repeated in her slow, deliberate Italian accent, as if she were unsure he quite understood. Her voice was low and throaty and appealing. More Novak than Kelly, he thought.

“Harvey's a drug-addled jerk. He never mentioned anything to me. We've got this opening ceremony tonight, in front of everyone from God down. The biggest and best movie of the decade and I get to do the honours.”

“It must be an honour to be in Signor Tonti's masterpiece.”

Allan Prime took a deep breath. “Without me it'd be nothing. You ever watch Gordy's Break?”

“I loved that movie,” she replied without hesitation, and he found himself liking the throaty, almost masculine croon in her voice.

“It was a pile of crap. If it wasn't for me, the thing wouldn't have made it outside the queer theatres.”

He truly hated that thing. The movie was the kind of violent fake art-house junk the Academy liked to smile on from time to time just to show it had a brain as well as a heart. He'd played a low-life hood in a homosexual relationship with a local priest who was knifed to death trying to save him. When the clamour petered out, and the golden statue was safely stored somewhere he didn't have to look at it, Allan Prime decided to make movies for people, not for critics. One a year for almost three decades. Nothing that followed gave him another nomination.

The lack of Oscars never bothered Prime too much, most of the time. From the eighties on he'd become more and more bankable, a multimillion-dollar name who always brought in an army of female fans in love with his chiselled Mediterranean looks, trademark wavy dark hair, and that slow, semi-lascivious smile he liked to throw in somewhere along the line.

Except now. He'd tried, and every time he began to crease up for the famed smirk, Roberto Tonti had gone stiff in his director's chair, thrown back his hoary aquiline head with its crown of grey hair like plumed feathers, and howled long and loud with fury.

“This is what I do,” Prime had complained one day, when the verbal abuse went too far. He was in costume, a long, grubby medieval gown, standing in front of a blue screen, pretending to deliver some obscure speech to a digitised dragon or some other monster out of a teenage horror fantasy, though he couldn't see a thing except lights and cameras and Roberto Tonti thrashing around in his chair like some ancient, skeletal wraith.

“Not when you work for me,” Tonti screamed at him. “When you work for me, you…”—a stream of impenetrable Italian curses followed—”…you are mine. My puppet. My creature. Every day I put my finger up your scrawny, coked-up ass, Allan, and every day I wiggle a little harder till your stupid brain wakes up. Stop acting. Start being.”

Stop acting. Start being. Prime had lost count of the number of times he'd heard that. He still didn't get it.

Tonti was seventy-three. He looked a hundred and fifty and was terminally ill, with a set of lungs that had been perforated by a lifetime's tobacco. Maybe he'd be dead before the movie got its first showing in the U.S. They all knew that was a possibility. It added to the buzz Simon Harvey's little army of evil PR geckos had been quietly building with their tame hacks.

Allan Prime had already thought through his performance in the director's real-life funeral scene. He'd release one single tear, dab it away with a finger, not a handkerchief, showing he was a man of the people, unchanged by fame. Then, when no one could hear, he'd walk up to the casket and whisper, “Where's that freaking finger now, huh?”

Or maybe the old bastard would live forever, long enough to dance on Prime's own grave. There was something creepy, something abnormal about the man, which was, the rumours said, why he'd not sat at the helm of a movie for twenty years, frittering away his talent in the wasteland of TV until Inferno came along. Prime gulped a fat finger of single malt, then refilled his glass from the bottle on the table. It was early, but the movie was done, and he didn't need to be out in public until the end of the day. The penthouse apartment atop one of the finest houses in the Via Giulia, set back from the busy Lungotevere with astonishing views over the river to St. Peter's, had been Allan Prime's principal home for almost a year. Tonight it was empty except for him and Miss Valdes.

“This is for publicity, right?” he asked.

“Sì,” the woman replied, and patted her briefcase like a lawyer sure it contained evidence. She had to be Italian. And the more he looked at her, the more Prime became convinced she wasn't unattractive either, with her full, muscular figure—that always turned him on—and very perfect teeth behind a mouth blazingly outlined in carmine lipstick. “Mr. Harvey say we must have a copy of your face, because we cannot, for reasons of taste, mass-market a version of the real thing. It must be you.”

“I cut myself shaving this morning. Does that matter?”

“I can work with that.”

“Great,” he grumbled. “So where do you want me?”

She took off her oversized sunglasses. Miss Valdes was a looker and Allan Prime was suddenly aware something was starting to twitch down below. She had a large, strong face, quite heavy with makeup for this time of day, as if she didn't just make masks, she liked wearing them herself. The voice, too, now that he thought about it, sounded artificial. Po

sed. As if she wasn't speaking in her natural tongue. Not that this worried him. He was aware of a possibility in her eyes, and that was all he needed.

“On the bed, sir,” Miss Valdes suggested. “It would be best if you were naked. A true death mask is always taken from a naked man.”

“Not that I'm arguing, but why the hell is that?”

The corner of her scarlet mouth turned down in a gesture of meek surprise, one that seemed intoxicatingly Italian to him.

“We come into the world that way. And leave it, too. You're an actor.”

He watched, rapt, as her fleshy, muscular tongue ran very deliberately over those scarlet lips.

“I believe you call it… being in character.”

He wondered how Roberto Tonti would direct a scene like this.

“Will it hurt?”

“Of course not!” She appeared visibly offended by the idea. “Who would wish to hurt a star?”

“You'd be surprised,” Prime grumbled. This curious woman would be truly amazed, if she only knew.

She smoothed down the front of her jacket, opened the briefcase, and peered into it with a professional, searching gaze before beginning to remove some items Allan Prime didn't recognise.

“First a little… discomfort,” she declared. “Then…” That carmine smile again, one Allan Prime couldn't stop staring at, although there was something about it that nagged him. Some thing familiar he couldn't place. “Then we are free.”

Miss Valdes—Carlotta Valdes, he recalled the first name the doorman had used when he'd called up to announce her arrival-took out a pair of rubber gloves and slipped them onto her strong, powerful hands, like those of a nurse or a surgeon.

AT FIVE MINUTES PAST FOUR, NIC COSTA FOUND himself standing outside a pale green wooden hut shaded by parched trees, just a short walk from the frenzied madness that was beginning to build in and around the nearby Casa del Cinema. The sight of this tiny place brought back far too many memories, some of them jogged by a newspaper clipping attached to the door, bearing the headline “ ‘Dei Piccoli,' cinema da Guinness.” This was the world's smallest movie theatre, built for children in 1934 during the grim Mussolini years, evidence that Italy was in love with film, with the idea of fantasy, of a life that was brighter and more colourful than reality, even in those difficult times. Or perhaps, it occurred to Costa now, with the perspective of adulthood shaping his childhood memories, because of them. This small oak cabin had just sixty-three seats, every one of them, he now felt sure, deeply uncomfortable for anyone over the age of ten. Not that his parents had ever complained. Once a week, until his eleventh birthday, his mother or father had brought him here. Together they had sat through a succession of films, some good, some bad, some Italian, some from other countries, America in particular.

It was a different time, a different world, both on the screen and in his head. Costa had never returned much to any cinema since those days. There had always seemed something more important to occupy his time: family and the slow loss of his parents; work and ambition; and, for comfort, the dark and enticing galleries and churches of his native city, which seemed to speak more directly to him as he grew older. Now he wondered what he'd missed. The movie playing was one he'd seen as a child, a popular Disney title prompting the familiar emotions those films always brought out in him: laughter and tears, fear and hope. Sometimes he'd left this place scarcely able to speak for the rawness of the feelings that the movie had, with cunning and ruthlessness, elicited from his young and fearful mind. Was this one reason why he had stayed away from the cinema for so long? That he feared the way it sought out the awkward, hidden corners of one's life, good and bad, then magnified them in a way that could never be shirked, never be avoided? Some fear that he might be haunted by what he saw?

He had been a widower for six months, before the age of thirty, and the feelings of desolation and emptiness continued to reverberate in the distant corners of his consciousness. The world moved on. So many had said that, and in a way they'd been right. He had allowed work to consume him, because there was nothing else. There, Leo Falcone had been subtly kind in his own way, guiding Costa away from the difficult cases, and any involving violence and murder, towards more agreeable duties, those that embraced culture and the arts, milieux in which Costa felt comfortable and, occasionally, alive. This was why, on a hot July day, he was in the pleasant park of the Villa Borghese, not far from three hundred or more men and women assembled from all over the world for a historic premiere that would mark the revival of the career of one of Italy's most distinguished and reclusive directors.

Costa had never seen a movie by Roberto Tonti until that afternoon, when, as a reward for their patient duties arranging property security for the exhibition associated with the production, the police and Carabinieri had been granted a private screening. He was still unclear exactly what he felt about the work of a man who was something of an enigmatic legend in his native country, though he had lived in America for many, many years. The movie was… undoubtedly impressive, though very long and extremely noisy. Costa found it difficult to recognise much in the way of humanity in all its evident and very impressive spectacle. His memories of studying Dante's Divina Commedia in school told him the lengthy poem was a discourse on many things, among them the nature of human and divine love, an argument that seemed absent from the film he had sat through. Standing outside the little children's cinema, it seemed to Costa that the Disney title it was now showing contained more of Dante's original message than Tonti's farrago of visual effects and overblown drama.

But he was there out of duty. The Carabinieri had been assigned to protect the famous actors involved in the year-long production at Cinecittà. The state police had been given a more mundane responsibility, that of safeguarding the historic objects assembled for an accompanying exhibition in the building next to the Casa del Cinema: documents and letters, photographs and an extensive exhibition of original paintings depicting the civil war between the Ghibellines and the Guelphs which prompted Dante's flight from Florence and brought about the perpetual exile in which he wrote his most famous work.

There was a photograph of the poet's grave and the verse of his friend Bernardo Canaccio that included the line…

Parvi Florentia mater amoris.

Florence, mother of little love, a sharp reminder of how Dante had been abandoned by his native city. There was a picture, too, of the tomb the Florentines had built for him in 1829, out of a tardy sense of guilt. The organisers' notes failed to disclose the truth of the matter, however: that his body remained in Ravenna. The ornate sepulchre in the Basilica di Santa Croce, built to honour the most exalted of poets, was empty. The poet remained an exile still, almost seven hundred years after his death.

The most famous Florentine object was, however, genuine. Hidden on a podium behind a rich blue curtain, due to be unveiled by the actor playing Dante before the premiere that evening, sat a small wooden case on a plinth. Inside, carefully posed against scarlet velvet, was the death mask of Dante Alighieri, cast in 1321 shortly after his last breath. That morning, Costa had found himself staring at these ancient features for so long that Gianni Peroni had walked over and nudged him back to life with the demand for a coffee and something to eat. The image still refused to quit his head: the ascetic face of a fifty-six-year-old man, a little gaunt, with sharp cheekbones, a prominent nose, and a mouth pinched tight with such deliberation that this mask, now grey and stained with age, seemed to emphasise I will speak no more.

Costa was uneasy about such a treasure being associated with the Hollywood spectacle that had invaded this quiet, beautiful hillside park in Rome. There had been a concerted and occasionally vitriolic campaign against the project in the literary circles of Rome and beyond. Rumours of sabotage and mysterious accidents on the film set had appeared regularly in the papers. The chatter in some of the gutter press suggested the production was “cursed” because of its impudent and disrespectful pillaging of Dante's work, an id

ea that had a certain appeal to the superstitious nature of many Italians. The response of Roberto Tonti had been to rush to the TV cameras denying furiously that his return to the screen was anything but an art movie produced entirely in the exalted spirit of the original.

The more sophisticated newspapers detected the hand of a clever PR campaign in all this, something the production's publicity director, Simon Harvey, had vigorously denied. Costa had watched the last press conference only the day before and come to the conclusion that he would never quite understand the movie industry. Simon Harvey was the last man he expected to be in charge of a production costing around a hundred and fifty million dollars, a good third over budget. Amiable, engaging, with a bouncing head of fair curly hair, Harvey appeared more like a perpetual fan than someone capable of dealing with the ravenous hordes of the world media. But Costa had seen him in private moments, too, when the PR director seemed calm and quick-thinking, though prone to brief explosions of anger.

The people Costa had met and worked with over the previous few weeks were, for the most part, charming, hardworking, and dedicated, but also, above all, obsessive. Nothing much mattered for them except the job in hand, Inferno. A war could have started, a bomb might have exploded in the centre of Rome. They would never have noticed. The world flickering on the screen was theirs. Nothing else existed.

Nic Costa rather envied them.

AN HOUR AFTER THEY HAD WALKED OUT FROM the private showing, blinking into the summer sun, Gianni Peroni's outrage had still not lessened. The big cop stood next to Leo Falcone and Teresa Lupo, elaborating on a heartfelt rant about the injustice of it all. The world. Life. The job. The fact they were guarding ancient wooden boxes and old letters when they ought to be out there doing what they were paid for.

The Garden of Angels

The Garden of Angels Solstice

Solstice Death in Seville

Death in Seville A Season for the Dead

A Season for the Dead The Killing tk-1

The Killing tk-1 The Savage Shore

The Savage Shore Dante's Numbers

Dante's Numbers Sacred Cut

Sacred Cut City of Fear nc-8

City of Fear nc-8 The Blue Demon

The Blue Demon The Garden of Evil

The Garden of Evil The Lizard's Bite

The Lizard's Bite The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Sleep Baby Sleep

Sleep Baby Sleep Lucifer's Shadow

Lucifer's Shadow Season for the Dead

Season for the Dead The Seventh Sacrament

The Seventh Sacrament The Garden of Evil nc-6

The Garden of Evil nc-6 Juliet & Romeo

Juliet & Romeo A Season for the Dead nc-1

A Season for the Dead nc-1 The Fallen Angel nc-9

The Fallen Angel nc-9 Little Sister

Little Sister The Lizard's Bite nc-4

The Lizard's Bite nc-4 The Killing 2

The Killing 2 The Fallen Angel

The Fallen Angel The Sacred Cut

The Sacred Cut Carnival for the Dead

Carnival for the Dead The Villa of Mysteries nc-2

The Villa of Mysteries nc-2 Macbeth

Macbeth The Killing - 01 - The Killing

The Killing - 01 - The Killing The Villa of Mysteries

The Villa of Mysteries Dante's Numbers nc-7

Dante's Numbers nc-7 The Sacred Cut nc-3

The Sacred Cut nc-3 The Seventh Sacrament nc-5

The Seventh Sacrament nc-5