- Home

- David Hewson

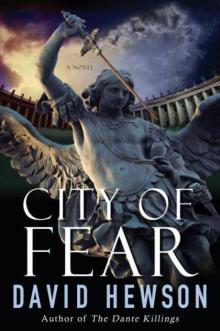

The Garden of Evil nc-6

The Garden of Evil nc-6 Read online

The Garden of Evil

( Nic Costa - 6 )

David Hewson

In a hidden studio in an area of Rome, where the Vatican liked to keep an eye on the city's prostitutes, an art expert from the Louvre is found dead in front of one of the most beautiful paintings that Nic Costa has ever seen — an unknown Caravaggio masterpiece.

But before long tragedy will strike Nic far closer to home. The main suspect's identity is known, but he remains untouchable — protected in his grand palazzo by a fleet of lawyers and a sinister cult known as the Ekstasists.

If Costa and his team can crack the reasons for the cult's existence, he may well stand a chance of nailing his wife's killer. But the mystery will take him right back to Caravaggio himself and the reasons he had to flee Rome, all those centuries before…

David Hewson

The Garden of Evil

PART ONE

One

Aldo Caviglia glimpsed his reflection in the overhead mirror of the crowded 64 bus. He was not a vain man but, on the whole, he approved of what he saw. Caviglia had recently turned sixty. Four years earlier he had lost his wife. There had been a brief, lost period when drink took its toll, and with it his job in the ancient bakery in the Campo dei Fiori, just a few minutes’ walk from the small apartment close to the Piazza Navona where they had lived for their entire married life. He had escaped the grip of the booze before it stole away his looks. The grief he still felt marked him only inwardly now.

Today he was wearing what he thought of as his winter Thursday uniform, a taupe woollen coat over a brown suit with a knife-edge crease running down the trousers. In his mind’s eye he was the professional man he would have been in another, different life. A minor academic, a civil servant, an accountant perhaps. Someone happy with his lot, and that, at least, was no lie.

It was December the eighth, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. Christmas stood on the horizon, its presence finally beginning to make itself known beyond the tawdry displays that had been in store windows for weeks. Every good Catholic would attend mass. The Pope would venerate two famous statues of the Virgin, in the Piazza di Spagna and at Santa Maria Maggiore. Catholic or not, families would flock to the city streets, to shop, to eat, to gossip, to walk around and enjoy the season. In the vast racetrack space of the Piazza Navona, which followed the lines of the Imperial stadium that had preceded it, the stalls occupied almost every last square metre: toys for the children, panini of porchetta carved straight from the warm pig’s carcass for the parents, and the Christmas witch, La Befana, everywhere, on stockings and pendants, decorations and candies, a half-hideous, half-friendly spectre primed to dispense gifts to the young at Epiphany.

Caviglia gripped the handrail as the bus lurched through the traffic past the stranded temple ruins of Largo di Torre Argentina, smiling at his memories. Theirs had been an uncomplicated, innocent marriage, perhaps because it had never been blessed by children. Even so, for Chiara’s sake, he had left out a traditional offering for La Befana — a piece of broccoli, some sausage, and a glass of wine — every year of their marriage, right to the end, when her life was ebbing away like a winter tide retreating gently for the last time. He’d never had the money for expensive presents. Nor did it matter, then or now. The pictures that still remained in his head — of rituals; of simple, fond, shared acts — were more valuable than any lump of gold or silver could ever have been. When his wife was alive, they served as visible symbols of his love. Now that he was alone, the memory of their giving provided comfort during the cold, solitary nights of winter. In his own mind Christmas remained what it always was: a turning point for the year at which the days ceased to shorten, Rome paused to look at itself, feel modestly proud of what it saw, then await the inevitable arrival of spring and, with it, rebirth.

Even in the weather the city had endured of late — dark and terribly wet, with the Tiber at its highest in a quarter century, so brown and muddy and reckless it would have burst its banks without the modern flood defences — there was a spirit of quiet excitement everywhere, a communal recollection of a small, distant miracle that still bore some significance in an ephemeral world of mundane, fleeting greed. He saw this in the faces of the children spilling down the city streets and alleys, excited, trying to guess what the coming weeks would bring. He saw this in the eyes of their parents, too, remembering their youth, taking pleasure in passing some fragment of the wonder on to their own offspring in return. Nor was the weather uniformly vile. Occasionally the heavy, dark clouds would break and a lively winter sun would smile on the city. He’d seen it drift through the dusty windows of his apartment that morning, spilling a welcome golden light onto the ancient, smoke-stained cobblestones of the alley outside. It had made him feel at home, glad to be a Roman born and bred.

* * *

Caviglia had lived in the Centro Storico all his life and worshipped in the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi around the corner. His wife had adored the paintings there, the Caravaggios in particular, with their loving and lifelike depiction of Matthew, at his conversion, during his work, and finally at his death. One December eighth, twenty-five years ago it must have been, Caviglia had marked their visit by spending what little money he had from his baker’s wages on a bouquet of bright red roses. Chiara had responded by choosing the most beautiful stem and pinning it into the strap of his floury overalls — he had come straight from work — then taking him in her arms in an embrace he could still recall for its strength and warmth and affection.

Ever since, even after she was gone, he had marked the day, first with roses, bought before breakfast from the small florist’s store that stood close to the piazza, then a brief visit to the church, where he lit a single candle in his wife’s memory. He no longer attended mass, though. It seemed unnecessary.

* * *

A single carmine stem from Tuscany sat in the left lapel of his woollen coat, its supple, insistent perfume rising above the diesel odour and the people smell of the bus, reminding him of times past and how, in those last few weeks of her illness, his wife had ordered him, in a voice growing ever weaker, to mourn for a short time only, then start his own life afresh.

To the widowed Aldo Caviglia there was no finer time to be in Rome, even in the grey, persistent rain. The best parts of the year lay ahead, waiting in store for those who anticipated them. And in the careless crowds of Christmas, flush with money, there was always business to be done.

* * *

He had an itinerary in mind, the one he always saved for the second Thursday in the month, since repetition was to be avoided. Having walked to Barberini for the exercise and taken a brief turn around the gallery, he had caught the 64 bus for the familiar journey through the city centre, following Vittorio Emanuele, then crossing the river by the Castel Sant’Angelo for the final leg towards St. Peter’s. Once there, he would retrace his steps as necessary until his goal was reached.

Caviglia both loved and hated the 64. No route in Rome attracted more tourists, which made it a beacon for the lesser members of his recently acquired profession. Many were simply confused and lost. Aldo Caviglia, an impeccably dressed man in later middle age, who wore a perpetual and charming smile and spoke good English, was always there to help. He maintained in his head a compendious knowledge of the city of his birth. Should his memory fail him, he always kept in his pocket a copy of Il Trovalinea, the comprehensive city transport guide that covered every last tram and bus in Rome. He knew where to stay, where to eat. He knew, too, that it was wise to warn visitors of the underside of Roman life: the petty crooks and bag-snatchers, the hucksters working the tourist traps, and the scruffy pickpockets who hung around the buses and the subway, the 64 in particular.

> He gave them tips. He taught them the phrase “Zingari! Attenzione!” explaining that it meant “Beware! Gypsies!” Not, he hastened to add, that he shared the common assumption all gypsies were thieves. On occasion he would amuse his audience by demonstrating the private sign every Roman knew, holding his hands down by his side, rippling his fingers as if playing the piano. He had a fine, delicate touch, that of an artist, which he demonstrated proudly with this gesture. Before the needs of everyday life had forced him to find more mundane work, he had toyed with the idea of painting as a profession, since the galleries of his native city, the great Villa Borghese, the splendid if chaotic Barberini, and his favourite, the private mansion of the Doria Pamphilj dynasty, were places he still frequented with a continuing sense of wonder.

The visitors always laughed at his subtle, fluttering fingertips. It was such a small, secret signal, yet as soon as one saw it there could be no doubting its meaning: the bus or the carriage had just been joined by a known pickpocket. Look out.

* * *

He was careful to keep records, maintained in a private code on a piece of paper hidden at the bottom of his closet. On a normal working day, Aldo Caviglia would not return home until he had stolen a minimum of 400. His average — Caviglia was a man fond of precise accounts — had been 583 over the past four weeks. On occasion — tourists sometimes carried extraordinary amounts of cash — he had far exceeded his daily target, so much so that it had begun to trouble him. Caviglia chose his victims carefully. He never preyed on the poor or the elderly. When one miserable Russian’s wallet alone yielded more than 2,000, Caviglia had decided upon a policy. All proceeds above his maximum of 650 would be donated anonymously — pushed in cash into a church collection box — to the sisters near the Pantheon who ran a charity for the city’s homeless. He prided himself on the fact that he was not a greedy man. Furthermore, as a true Roman he never ceased to be shocked by how the city’s population of destitute barboni, many young, many unable to speak much Italian, had grown in recent years. He would take no more than he needed. He would maintain a balance between his activities and his conscience, going out to steal one or two days each week, when necessary. For the rest of the time he would simply ride the trams and buses for the pleasure of being what, on the surface, he appeared: a genial Good Samaritan, always ready to help the stranded, confused foreigner.

* * *

The bus lurched away from the bus stop. The traffic was terrible, struggling through the holiday crowds at a walking pace. They had moved scarcely thirty metres along Vittorio Emanuele in the past five minutes. He stared at himself in the bus driver’s mirror again. Was this the face of a guilty man? Caviglia brushed away the thought. In truth, if he wanted to, he could probably get a job in a bakery, now that he was sober. No one ever complained about his work. His late wife had thought him among the best bakers in Rome. There was a joke he now made to himself: These fingers can make dough, these fingers can take dough. It was a good one, he thought. He wished he could share it with someone.

If I wanted to, Caviglia emphasised to himself.

You feel guilty, said a quiet, inner voice, for yourself and the life you are wasting. Not for what you’ve done.

He glanced out of the grimy windows: solid lines of cars and buses and vans stood stationary in both directions. The sudden joy of the coming holiday vanished.

To his surprise, Aldo Caviglia felt a firm finger prod hard into his chest.

“I want the stop for the Vicolo del Divino Amore,” said a woman hard up against his right side. She spoke in an accent Caviglia took to be French, with a confidence in her Italian which was, he felt, somewhat ill-judged.

He turned to look at her, aware that his customary smile was no longer present.

She was attractive, though extremely slender, and wore a precisely cut short white gabardine coat over a tube-like crayon-red leather skirt that stopped just above the knee. Perhaps thirty-five, she had short, very fiery red hair to match the skirt, acute grey eyes, and the kind of face one saw in advertisements for cosmetics: geometrically exact, entirely lacking in flaws, and, to Caviglia’s taste, somewhat two-dimensional. She seemed both nervous and a little depressed. And also ill, perhaps, since on second consideration her skin was very pale indeed, almost the colour of her jacket, and her cheeks hollow.

She had a large fawn pigskin bag over her shoulder. It sported the very visible badge of one of the larger Milan fashion houses. Caviglia wondered why a beautiful woman, albeit one of daunting and somewhat miserable appearance, would want to advertise the wares of the Milanese clothes crooks and, by implication, her own sense of insecurity. The bag was genuine, though. Perhaps one thousand euros had been squandered on that modest piece of leather. The zip was halfway open, just enough to reveal a large collection of items — a scarf, a phone, some pens, and a very large, overstuffed wallet.

“I really need to find this place,” she told him. “It’s near the Palazzo Malaspina, I know. But I was never very good at directions. I’ve only been there at night. I…”

For a moment he feared she was about to burst into tears. Then he corrected himself. She was simply absorbed, in what he could not begin to imagine.

Caviglia smiled, then reached over her to press the bell. A cloud of rich, somewhat cloying perfume rose from her body. French, he thought again.

“The next stop, signora, if you are willing to walk. I will show you where to go. I have to get off myself in any case.”

She nodded and said nothing. When the bus finally came to a halt, Caviglia put a protective arm around her and pushed through the milling mob to exit by the front doors, as a local would, in spite of the rules, saying loudly as he forced his way forward, “Permesso. Permesso! PERMESSO!”

He waited for her to alight from the bus, his hands behind his back. Out in the brief bright light of this December day, she seemed even more frail and thin.

“It’s ten minutes on foot,” Caviglia said. He pointed across the road. “In that direction. There are no buses. Perhaps I can find you a taxi.”

“I can walk,” she said instantly.

“Can you find your way to the Piazza Navona from here?”

She nodded and looked a little offended. “Of course!”

“Go to the end,” he instructed. “Then turn right through the Piazza Agostino for the Via della Scrofa. Turn right again at the Piazza Firenze and you will find the Vicolo del Divino Amore on your left along the Via dei Prefetti.”

“Thank you.”

“You are entering an interesting part of my city. Many famous artists lived there. It was once part of the area called ‘Ortaccio.’ ”

She looked puzzled. “My Italian is bad. I don’t know that word.”

Caviglia cursed his stupidity for mentioning this fact. Sometimes he spoke too much for his own good.

“It was an area set aside by the Popes for prostitutes. Orto may signify the Garden of Eden. Ortaccio signifies what came after our discovery of sin. The Garden of Humanity. Or the Garden of Wickedness or Evil. Or one and the same. But I am simply a… retired schoolteacher. What would I know of such things?”

The merest of smiles slipped across her face. Though almost skeletally thin, she was exceptionally beautiful, Caviglia realised. It was simply that something — life, illness, or some inner turmoil — disguised this fact most of the time, stood between her true self and others like a semi-opaque screen, one held by her own pale, slim hands.

“You know a lot, I think,” the Frenchwoman said. “You’re a kind man.” She stopped, smiled briefly again, and held out her hand. Caviglia shook it, delicately, since her fingers seemed so thin they might break under the slightest pressure. To his surprise her flesh was unexpectedly warm, almost as if something burned inside her, with the same heat signified by her fiery hair.

Then she took a deep breath, looked around — seeming to take an unnecessary pleasure in the smog-stained stones of a busy thoroughfare Caviglia regarded as one of the most uninteresti

ng in Rome — and was gone, threading through the traffic with a disregard for her own safety he found almost heart-stopping.

He turned away before her darting white form, like an exclamation mark with a full stop made from flame, disappeared into one of the side roads leading to the Piazza Navona.

Business was business. Caviglia patted the right-hand side of his jacket pocket. The woman’s fat wallet sat there, a wad of leather and paper and credit cards waiting to be stripped. Experience and his own intelligence told him the day’s work was over. Nevertheless, he was a little disturbed by this encounter. There was something strange about this woman in white, and her urgent need to go the Vicolo del Divino Amore, a dark Roman alley that, to him, showed precious little trace of divine love, and probably never had.

Two

Aldo Caviglia strode towards the Campo Dei Fiori and entered a small cafe located in one of the side roads leading to the Cancelleria, determined to count his gains, then dump the evidence. This particular hole in the wall was a place he’d always liked: too tiny and local to be of interest to tourists, and one that kept to the old tradition of maintaining a bowl of thick, sticky mixed sugar and coffee on the bar so that those in need of a faster, surer fix could top up their caffè as much as was needed.

All the same, Caviglia had added a shot of grappa to his cup, also, something he hadn’t done for some months. This chill, strange winter day seemed to merit that, though it was still only twenty to eleven in the morning.

Within five minutes he was inside the tiny washroom, crammed up against the cistern, struggling, with trembling fingers, to extract what was of value from the bulging leather purse.

Caviglia never took credit cards. Partly because this would increase the risk but also, more important, out of simple propriety. He believed people should be robbed once and once only — by his nimble fingers and no others. That way the pain — and there would be pain, which might not merely be financial — would be limited to a few days or possibly a week. Nor would Caviglia look at the private, personal belongings which people carried with them in their daily lives. He had done this once, the first time he had been reduced to thieving on the buses to make ends meet. It had made him feel dirty and dishonourable. His criminality would always be limited to stealing money from those he judged could afford it, then passing on the excess to the kind and charitable nuns near the Pantheon. As a Catholic in thought if not in deed, he was unsure whether this was sufficient to guarantee him salvation, if such a thing existed. But it certainly helped him sleep at night.

The Garden of Angels

The Garden of Angels Solstice

Solstice Death in Seville

Death in Seville A Season for the Dead

A Season for the Dead The Killing tk-1

The Killing tk-1 The Savage Shore

The Savage Shore Dante's Numbers

Dante's Numbers Sacred Cut

Sacred Cut City of Fear nc-8

City of Fear nc-8 The Blue Demon

The Blue Demon The Garden of Evil

The Garden of Evil The Lizard's Bite

The Lizard's Bite The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Sleep Baby Sleep

Sleep Baby Sleep Lucifer's Shadow

Lucifer's Shadow Season for the Dead

Season for the Dead The Seventh Sacrament

The Seventh Sacrament The Garden of Evil nc-6

The Garden of Evil nc-6 Juliet & Romeo

Juliet & Romeo A Season for the Dead nc-1

A Season for the Dead nc-1 The Fallen Angel nc-9

The Fallen Angel nc-9 Little Sister

Little Sister The Lizard's Bite nc-4

The Lizard's Bite nc-4 The Killing 2

The Killing 2 The Fallen Angel

The Fallen Angel The Sacred Cut

The Sacred Cut Carnival for the Dead

Carnival for the Dead The Villa of Mysteries nc-2

The Villa of Mysteries nc-2 Macbeth

Macbeth The Killing - 01 - The Killing

The Killing - 01 - The Killing The Villa of Mysteries

The Villa of Mysteries Dante's Numbers nc-7

Dante's Numbers nc-7 The Sacred Cut nc-3

The Sacred Cut nc-3 The Seventh Sacrament nc-5

The Seventh Sacrament nc-5