- Home

- David Hewson

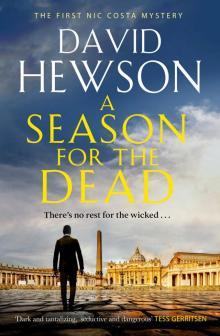

A Season for the Dead

A Season for the Dead Read online

David Hewson is a former journalist with The Times, The Sunday Times and the Independent. He is the author of more than twenty-five novels including his Rome-based Nic Costa series which has been published in fifteen languages.

He has also written three acclaimed adaptations of the Danish TV series The Killing.

@david_hewson davidhewson.com

Also by David Hewson

The Nic Costa Mysteries

The Villa of Mysteries

The Sacred Cut

The Lizard’s Bite

The Seventh Sacrament

The Garden of Evil

Dante’s Numbers

The Blue Demon

The Fallen Angel

The Savage Shore

The Killing

Part I

Part II

Part III

This edition published in Great Britain, the USA and Canada in 2020

by Black Thorn, an imprint of Canongate Books Ltd,

14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

Distributed in the USA by Publishers Group West and in Canada by Publishers Group Canada

Published in Great Britain 2018 by Severn House Publishers Ltd,

Eardley House, 4 Uxbridge Street, London W8 7SY

blackthornbooks.com

This digital edition first published in 2020 by Canongate Books

Copyright © David Hewson, 2003

The right of David Hewson to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Except where actual historical events and characters are being described for the storyline of this novel, all situations in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events or locales is purely coincidental.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 83885 064 7

eISBN 978 1 83885 065 4

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-One

Chapter Fifty-Two

Chapter Fifty-Three

Chapter Fifty-Four

Chapter Fifty-Five

Chapter Fifty-Six

Chapter Fifty-Seven

Chapter Fifty-Eight

Chapter Fifty-Nine

Chapter Sixty

Chapter Sixty-One

Chapter Sixty-Two

Chapter Sixty-Three

Chapter Sixty-Four

Chapter Sixty-Five

Chapter Sixty-Six

ONE

The heat was palpable, alive. Sara Farnese sat at her desk in the Reading Room of the Vatican Library and stared out of the window, out into the small rectangular courtyard, struggling to concentrate. The fierce August afternoon placed a rippling, distorting mirage across her view. In the unreal haze, the grass was a yellow, arid mirror of the relentless sun. It was now two o’clock. Within an hour the temperature beyond the glass would hit forty degrees. She should have left like everyone else. Rome in August was an empty furnace echoing to the whispers of desiccated ghosts. The university corridors on the other side of the city rang to her lone footsteps that morning. It was one reason she decided to flee elsewhere. Half the shops and the restaurants were closed. The only life was in the parks and the museums, where stray groups of sweating tourists tried to find some meagre shade.

This was the worst of the summer. Yet she had decided to stay. She knew why and she wondered whether she was a fool. Hugh Fairchild was visiting from London. Handsome Hugh, clever Hugh, a man who could rattle off from memory the names of every early Christian codex lodged in the museums of Europe, and had probably read them too. If the plane was on time he would have arrived at Fiumicino at ten that morning and, by now, have checked into his suite at the Inghilterra. It was too early for him to stay with her, she knew that, and pushed from her head the idea that there could be other names in his address book, other candidates for his bed. He was an intensely busy man. He would be in Rome for five days, of which two nights alone were hers, then move on to a lawyers’ conference in Istanbul.

It was, she thought, possible that he had other lovers. No, probable. He lived in London, after all. He had abandoned academia to become a successful career civil servant with the EU. Now he seemed to spend one week out of every four on the road, to Rome, to New York, to Tokyo. They met, at most, once a month. He was thirty-five, handsome in a way that was almost too perfect. He had a long, muscular, tanned body, a warm, aristocratic English face, always ready to break into a smile, and a wayward head of blond hair. It was unthinkable that he did not sleep with other women, perhaps at first meeting. That was, she recalled, with a slight sensation of guilt, what had happened to her at the convention on the preservation of historical artefacts in Amsterdam four months before.

Nor did it concern her. They were both single adults. He was meticulously safe in his lovemaking. Hugh Fairchild was a most organized man, one who entered her life and left it at irregular intervals which were to their mutual satisfaction. That night they would eat in her apartment close to the Vatican. They would cross the bridge by the Castel Sant’Angelo, walk the streets of the centro storico and take coffee somewhere. Then they would return to her home around midnight where he would stay until the morning, when meetings would occupy him for the next two days. This was, she thought, an ample provision of intellectual activity, pleasant company and physical fulfilment. Enough to keep her happy. Enough, a stray thought said, to quell the doubts.

She tried to focus on the priceless manuscript sitting on the mahogany desk by the window. This was a yellow volume quite unlike those Sara Farnese normally examined in the Vatican Reading Room: a tenth-century copy of De Re Coquinaria, the famed imperial Roman cookery book by Apicius from the first century AD. She would make him a true Roman meal: isicia omentata, small beef fritters with pine kernels, pullus fiusilis, chicken stuffed with herbed dough, a

nd tiropatinam, a soufflé with honey. She would explain that they were eating in because it was August. All the best restaurants were shut. This was not an attempt to change the status of their relationship. It was purely practical and, furthermore, she enjoyed cooking. He would understand or, at the very least, not object.

‘Apicius?’ asked a voice from behind, so unexpected it made her shudder.

She turned to see Guido Fratelli smiling at her with his customary doggedness. She tried to return the gesture though she was not pleased to see him. The Swiss Guard always made for her whenever she visited. He knew – or had learned – enough of her work in the library to be able to strike up a conversation. He was about her own age, running to fat a little, and liked the blue, semi-medieval uniform and the black leather gun holster a little too much. As a quasi-cop he had no power beyond the Vatican, and only the quieter parts of that. The Rome police retained charge of St Peter’s Square which was, in truth, the only place the law was usually needed. And they were a different breed, nothing like this quiet, somewhat timorous individual. Guido Fratelli would not last a day trying to hustle the drunks and addicts around the Termini Station.

‘I didn’t hear you come in,’ Sara said, hoping he took this as a faint reproach. The Reading Room was empty apart from her. She appreciated the quiet; she did not want it broken by conversation.

‘Sorry.’ He patted the gun on his belt, an unconscious and annoying gesture. ‘We’re trained to be silent as a mouse. You never know.’

‘Of course,’ she replied. If Sara recalled correctly, there had been three murders in the Vatican in the course of almost two hundred years: in 1988, when the incoming commander of the Swiss Guard and his wife were shot dead by a guard corporal harbouring a grudge, and in 1848, when the Pope’s prime minister was assassinated by a political opponent. With the city force taking care of the crowds in the square, the most Guido Fratelli had to worry about was an ambitious burglar.

‘Not your usual stuff?’ he asked.

‘I’ve wide-ranging interests.’

‘Me too.’ He glanced at the page. The volume had come in its customary box, with the name in big, black letters on the front, which was how he knew what she was reading. Guido was always hunting for conversational footholds, however tenuous. Perhaps he thought that was a kind of detective work. ‘I’m learning Greek, you know.’

‘This is Latin. Look at the script.’

His face fell. ‘Oh. I thought it was Greek you looked at. Normally.’

‘Normally.’ She could see the distress on his face and couldn’t help being amused. He was thinking: I have to try to learn both?

‘Maybe you could tell me how I’m doing some time?’

She tapped the notebook computer onto which she had transcribed half the recipes she wanted.

‘Some time. But not now, Guido. I’m busy.’

The desk was at right angles to the window. She looked away from him, into the garden again, seeing his tall, dark form in the long window. Guido was not going to give up easily.

‘OK,’ he said to her reflection in the glass, then walked off, back down to the entrance. She heard laughter through the floor from the long gallery above. The tourists were in, those who had sufficient influence to win a ticket to these private quarters. Did they understand how lucky they were? Over the last few years, both as part of her role as a lecturer in early Christianity at the university and for purely personal pleasure, she had spent more and more time in the library, luxuriating in the astonishing richness of its collection. She had touched drawings and poems executed in Michelangelo’s own hand. She had read Henry VIII’s love letters to Anne Boleyn and a copy of the same king’s Assertio Septem Sacramentorum, signed by the monarch, which had won Henry the title ‘Defender of the Faith’ and still failed to keep him in the Church.

From a professional point of view it was the early works – the priceless codices and incunabula – which were the focus of her constant attention. Even so, she was unable to prevent herself stealing a glance at the personal material from the Middle Ages on. In a sense, she felt she had listened to Petrarch and Thomas Aquinas in person. Their voices remained, like dead echoes on the dry vellum and the ancient stain of ink they had left on the page. These traces made them human and, for all their wisdom, for all their skill with words, without their humanity they were nothing, though Hugh Fairchild would probably disagree.

There was a noise from the entrance, a half shout, not loud in itself but, given the context, disturbing. No one ever shouted in the Reading Room of the Vatican Library.

Sara raised her head and was surprised to see a familiar figure walking towards her. He moved briskly through the bands of sharp light that fell through the window, with a swift, determined intent that seemed out of place in these surroundings, wrong. The air-conditioning rose in volume. A chill blanket of air fell over her and she shivered. She looked again. Stefano Rinaldi, a fellow professor at the university, carried a large, bulging plastic bag and was crossing the empty Reading Room with a determined stride. There was an expression on his round, bearded face which she failed to recognize: anger or fear or a combination of both. He was wearing his customary black shirt and black trousers but they were dishevelled and there were what looked like wet stains on both. His eyes blazed at her.

For no reason, Sara Farnese felt frightened of this man whom she had known for some time.

‘Stefano …’ she said softly, perhaps so quietly he was unable to hear.

The commotion was growing behind him. She saw figures waving their arms, beginning to race after the figure in black with the strange, full supermarket bag dangling from his right hand. And from his left, she saw now, something even odder: what appeared to be a gun, a small black pistol. Stefano Rinaldi, a man she had never known to show anger, a man for whom she once felt a measure of attraction, was walking purposefully across the room in her direction holding a gun, and nothing she could imagine, no possible sequence of events, could begin to explain this.

She reached over, placed both hands on the far side of the desk and swung it round through ninety degrees. The old wood screeched on the marble floor like an animal in pain. She heaved at the thing until her back was against the glass and the desk was tight against her torso, not questioning the logic: that she must remain seated, that she must face this man, that this ancient desk, with a tenth-century copy of a Roman recipe book and a single notebook computer on it, would provide some protection against the unfathomable threat that was approaching her.

Then, much more quickly than she expected, he was there, gasping for breath above her, that crazy look more obvious than ever in his dark-brown eyes.

He sat down in the chair opposite and peered into her face. She felt her muscles relax, if only a little. At that moment, Sara was unafraid. He was not there to harm her. She understood that with an absolute certainty that defied explanation.

‘Stefano …’ she repeated.

There were shapes gathering behind him. She could see Guido Fratelli there. She wondered how good he was with his gun and whether, by some unfortunate serendipity, she might die that day from the stray bullet of an inexperienced Swiss Guard with a shaking hand that pointed the gun at a former lover of hers who had, for some reason, gone mad in the most venerated library in Rome.

Stefano’s left arm, the one holding the weapon, swept the table, swept everything on it, the precious volume of Apicius, her expensive notebook computer, down to the hard marble floor with a clatter.

She was quiet, waiting, which was, his eyes seemed to say, what he wanted.

Then Stefano lifted up the bag to the height of the desk, turned it upside down, let the contents fall on to the table and said, in a loud, commanding voice that was half crazy, half dead, ‘The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church.’

She looked at the thing in front of her. It had the consistency of damp new vellum, as if it had just been rinsed. Apicius would have written on something very like this once it was

dry.

Still holding the gun with his left hand, Stefano began to unravel the pliable thing before her, stretching it, extending the strange fabric until it filled the broad mahogany top of the desk then flowed over the edges, taking as it did a shape that was both familiar and, in its present context, foreign.

Sara forced her eyes to remain open, forced herself to think hard about what she was seeing. The object which Stefano Rinaldi was unfolding, smoothing out carefully with the flat palm of his right hand as if it were a tablecloth perhaps, on show for sale, was the skin of a human being, a light skin somewhat tanned, and wet, as if it had been recently washed. It had been cut roughly from the body at the neck, genitals, ankles and wrist, with a final slash down the spine and the back of the legs in order to remove it as a whole piece and Sara had to fight to stop herself reaching out to touch the thing, just to make sure this was not some nightmare, just to know.

‘What do you want?’ she asked, as calmly as she could.

The brown eyes met hers then glanced away. Stefano was afraid of what he was doing, quite terrified, yet there was some determination there too. He was an intelligent man, not stubborn, simply single-minded in his work which was, she now recalled, centred around Tertullian, the early Christian theologian and polemicist whose famous diktat he had quoted.

‘Who are the martyrs, Stefano?’ she asked. ‘What does this mean?’

He was sane at that moment. She could see this very clearly in his eyes, which had become calm. Stefano was thinking this through, looking for a solution.

He leaned forward. ‘She’s still there, Sara,’ he said, in the tobacco-stained growl she recognized, but speaking very softly, as if he wished no one else to hear. ‘You must go. Look at this.’ He stared at the table and the skin on it. ‘I daren’t …’ There was terror in his face though, in the context it seemed ridiculous. ‘Think of Bartholomew. You must know.’

Then, in a much louder voice, one that had the craziness back inside it again, he repeated Tertullian, ‘The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church.’

Stefano Rinaldi, his eyes now black and utterly lost, lifted the gun, raised it until the short, narrow barrel pointed at her face.

The Garden of Angels

The Garden of Angels Solstice

Solstice Death in Seville

Death in Seville A Season for the Dead

A Season for the Dead The Killing tk-1

The Killing tk-1 The Savage Shore

The Savage Shore Dante's Numbers

Dante's Numbers Sacred Cut

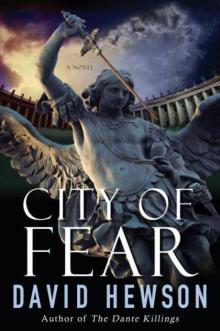

Sacred Cut City of Fear nc-8

City of Fear nc-8 The Blue Demon

The Blue Demon The Garden of Evil

The Garden of Evil The Lizard's Bite

The Lizard's Bite The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Sleep Baby Sleep

Sleep Baby Sleep Lucifer's Shadow

Lucifer's Shadow Season for the Dead

Season for the Dead The Seventh Sacrament

The Seventh Sacrament The Garden of Evil nc-6

The Garden of Evil nc-6 Juliet & Romeo

Juliet & Romeo A Season for the Dead nc-1

A Season for the Dead nc-1 The Fallen Angel nc-9

The Fallen Angel nc-9 Little Sister

Little Sister The Lizard's Bite nc-4

The Lizard's Bite nc-4 The Killing 2

The Killing 2 The Fallen Angel

The Fallen Angel The Sacred Cut

The Sacred Cut Carnival for the Dead

Carnival for the Dead The Villa of Mysteries nc-2

The Villa of Mysteries nc-2 Macbeth

Macbeth The Killing - 01 - The Killing

The Killing - 01 - The Killing The Villa of Mysteries

The Villa of Mysteries Dante's Numbers nc-7

Dante's Numbers nc-7 The Sacred Cut nc-3

The Sacred Cut nc-3 The Seventh Sacrament nc-5

The Seventh Sacrament nc-5