- Home

- David Hewson

The Blue Demon

The Blue Demon Read online

ALSO BY DAVID HEWSON

———

A Season for the Dead

The Villa of Mysteries

The Sacred Cut

The Lizard’s Bite

The Seventh Sacrament

The Garden of Evil

Lucifer’s Shadow

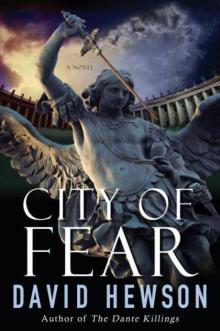

The Dante Killings

(originally Dante’s Numbers)

Contents

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Part Two

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Part Three

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Part Four

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Part Five

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Part Six

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Part Seven

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Author’s Note

About the Author

Copyright

PART ONE

Divination

Fere libenter homines id quod volunt credunt.

Men willingly believe what they wish.

—Julius Caesar, De Bello Gallico,

Book III, Chapter 18

1

THE GARDEN OF THE QUIRINALE FELT LIKE A SUN TRAP as the man in the silver armor strode down the shingle path. He was sweating profusely inside the ceremonial breastplate and woolen uniform.

Tight in his right hand he held the long, bloodied sword that had just taken the life of a man. In a few moments he would kill the president of Italy. And then? Be murdered himself. It was the fate of assassins throughout the ages, from Pausanius of Orestis, who had slaughtered Philip, the father of Alexander the Great, to Marat’s murderess, Charlotte Corday, and Kennedy’s nemesis, Lee Harvey Oswald.

The stabbing dagger, the sniper’s rifle … all these were mirrored weapons, reflecting on the man or woman who bore them, joining perpetrator and victim as twin sacrifices to destiny. It had always been this way, since men sought to rule over others, circumscribing their desires, hemming in the spans of their lives with the dull, rote strictures of convention. Petrakis had read much over the years, thinking, preparing, comparing himself to his peers. Actor John Wilkes Booth’s final performance before he put a bullet through the skull of Abraham Lincoln had been in Julius Caesar, although through some strange irony he had taken the part of Caesar’s friend and apologist, Mark Antony, not Brutus as history demanded.

As he approached the figure in the bower, seeing the old man’s gray, lined form bent deep over a book, Petrakis found himself murmuring a line Booth must have uttered a century and a half before.

“‘O mighty Caesar … dost thou lie so low? Are all thy conquests, glories, triumphs, spoils, shrunk to this little measure?’”

A pale, long face, with sad, tired eyes, looked up from the page. Petrakis, realizing he had spoken out loud, wondered why this death, among so many, would be the most difficult.

“I didn’t quite catch that,” Dario Sordi said in a calm, unwavering voice, his eyes, nevertheless, on the long, bloodied blade.

The uniformed officer came close, stopped, repeated the line, and held the sword over the elderly figure seated in the shadow of a statue of Hermes.

The president glanced around him and asked, “What conquests in particular, Andrea? What glories? What spoils? Temporary residence in a garden fit for a pope? I’m a pensioner in a very luxurious retirement home. Do you really not understand that?”

The weapon trembled in Petrakis’s hand. His palm felt sweaty. He couldn’t speak.

Voices rose behind him. A shout. A clamor.

There was a cigarette in Dario Sordi’s hand. It didn’t even shake.

“You should be afraid, old man.”

More dry laughter. “I’ve been hunted by Nazis.” The gray, drawn face glowered at him. Sordi drew on the cigarette and exhaled a cloud of smoke. “Played hide-and-seek with tobacco and the grape for more than half a century. Offended people—important people—who feel I am owed a lesson. Which is probably true.” A long, pale finger jabbed the evening air. “And now you wish me to cower before someone else’s puppet? A tool?”

That, at least, made it easier.

Petrakis found his mind ranging across so many things: memories, lost decades, languid days dodging NATO patrols beneath the Afghan sun, distant half-recalled moments in the damp darkness of an Etruscan tomb, talking to his father about life and the world, and how a man had to make his own way, not let another create a future for him.

Everything came from that place in the Maremma, from the whispered discovery of a paradise of the will sacrificed to the commonplace and mundane, the exigencies of politics. Andrea Petrakis knew this course was set for him at an early age, by birth, by his inheritance.

The memory of the tomb, with its ghostly painted figures on the wall, and the terrible, eternal specter of the Blue Demon, consuming them one by one, filled his head. This, more than anything else, he had learned over the decades: Freedom, of the kind enjoyed by the long-dead men and women still dancing beneath the gray Tarquinia earth more than two millennia on, was a mayfly, gloriously fleeting, made real only by its impermanence. Life and death were bedfellows, two sides of the same coin. To taste every breath, feel each beat of the heart, one had to know that both might be snatched away in an instant. His father had taught him that, long before the Afghans and the Arabs tried to reveal the same truth.

Andrea Petrakis remembered the lesson more keenly now, as the sand trickled through some unseen hourglass for Dario Sordi and his allotted assassin.

Out of the soft evening came a bright, sharp sound, like the ping of some taut yet invisible wire, snapping under pressure.

A piece of the statue of Hermes, its stone right foot, disintegrated in front of his eyes, shattering into pieces, as if exploding in anger.

Dario Sordi ducked back into the shadows, trying, at last, to hide.

2

Three days earlier …

“BEHOLD,” SAID THE MAN, IN A COLD

, TIRED VOICE, THE accent from the countryside perhaps. “I will make a covenant. For it is something dreadful I will do to you.”

Strong, firm hands ripped off the hood. Giovanni Batisti saw he was tethered to a plain office chair. At the periphery of his vision, he could make out that he was in a small, simple room with bare bleached floorboards and dust ghosts on the walls left by long-removed chests of drawers or ancient filing cabinets. The place smelled musty, damp, and abandoned. He could hear the distant lowing of traffic, muffled in some curious way, but still energized by the familiar rhythm of the city. Cars and trucks, buses and people, thousands of them, some from the police and the security services no doubt, searching as best they could, oblivious to his presence. There was no human sound close by, from an adjoining room or an apartment. Not a radio or a TV set. No voice save that of his captor.

“I would like to use the bathroom, please,” Batisti said quietly, keeping his eyes fixed on the stripped, cracked timber boards at his feet. “I will do as you say. You have my word.”

The silence, hours of it, had been the worst part. He’d expected a reprimand, might even have welcomed a beating, since all these things would have acknowledged his existence. Instead … he was left in limbo, in blindness, almost as if he were dead already. Nor was there any exchange he could hear between those involved. A brief meeting to discuss tactics. News. Perhaps a phone call in which he would be asked to confirm that he was still alive.

Even—and this was a forlorn hope, he knew—some small note of concern about his driver, Elena Majewska, everyone’s favorite, shot in the chest as the two vehicles blocked his government car in the narrow street of Via delle Quattro Fontane, at the junction with the road to the Quirinale. It was such a familiar Roman crossroads, next to Borromini’s fluid baroque masterpiece of San Carlino, a church he loved deeply and would visit often if he had time during his lunch break from the Interior Ministry building around the corner.

They could have snatched him that day from beneath Borromini’s dome, with its magnificent dove of peace, descending to earth from Heaven. He’d needed a desperate fifteen-minute respite from sessions with the Americans, the Russians, the British, the Germans.… Eight nations, eight voices, each different, each seeking its own outcome. The phrase that was always used about the G8—the “industrialized nations”—struck him as somewhat ironic as he listened to the endless bickering about diplomatic rights and protocols, about who should stand where and with whom. Had some interloper approached him during his brief recess that day, Batisti would have glanced at Borromini’s extraordinary interior one last time, then walked into his captor’s arms immediately. Anything but another session devoted to the rites and procedures of diplomatic life.

Then he remembered again, with a sudden, painful seizure of guilt, the driver. Did Elena—a young, pretty single mother who’d moved to Rome from Poland to find security and a better life—survive? If so, what could she tell the police? What was there to say about a swift and unexpected explosion of violence in the black sultry velvet of a Roman summer night? The attack had happened so quickly and with such brutish force that Batisti was still unsure how many men had been involved. Perhaps no more than three or four, to judge from the pair of vehicles blocking the way. The area was empty. He was without a bodyguard. An opposition politician drafted into the organization team was deemed not to need a bodyguard, even in the heightened security that preceded the summit. Not a single sentence was spoken as they dragged him from the rear seat, wrapped a blindfold tightly around his head, fired—three, four times?—into the front, then bundled him into the trunk of some large vehicle and drove a short distance to their destination.

Were they now issuing ransom demands? Did his wife, who was with her family in Milan, discussing a forthcoming family wedding, know what was happening?

There were no answers, only questions. Giovanni Batisti was forty-eight years old and felt as if he’d stepped back into a past that Italy hoped was behind it. The dismal seventies and eighties, the “Years of Lead.” A time when academics and lawyers and politicians were routinely kidnapped by the shadowy criminals of the Red Brigades and their partners in terrorism, held for ransom, tortured, then left bloodied and broken as some futile lesson to those in authority. Or dead. Like Aldo Moro, the former prime minister, seized in 1978, held captive for fifty-six days before being shot ten times in the chest and dumped in the trunk of a car in the Via Caetani.

“Look at me,” a voice from ahead of him ordered.

Batisti closed his eyes, kept them tightly shut. “I do not wish to compromise you, sir. I have a wife. Two sons. One is eight. One is ten. I love them. I wish you no harm. I wish no one any harm. These matters can and will be resolved through dialogue, one way or another. I believe that of everything. In this world, I have to.” He found his mouth was dry, his lips felt painful as he licked them. “If you know me, you know I am a man of the left. The causes you espouse are often the causes I have argued for. The methods—”

“What do you know of our causes?”

“I … I have some money,” Batisti stuttered. “Not of my own, you understand. My father. Perhaps if I might make a phone call?”

“This is not about money,” the voice said, and it sounded colder than ever. “Look at me or I will shoot you this instant.”

Batisti opened his eyes and stared straight ahead, across the bare, dreary room. The man seated opposite him was perhaps forty. Or a little older, his own age even. Professional-looking. Maybe an academic himself. Not a factory worker, not someone who had risen from poverty, pulled up by his own boot laces. There was a cultured timbre to his voice, one that spoke of education and a middle-class upbringing. A keen, incisive intelligence burned in his dark eyes. His face was leathery and tanned as if it had spent too long under a bright, burning sun. He would once have been handsome, but his craggy features were marred by a network of frown lines, on the forehead, at the edge of his broad, full-lipped mouth, which looked as if a smile had never crossed it in years. His long, unkempt hair seemed unnaturally gray and was wavy, shiny with some kind of grease. A mark of vanity. Like the black clothes, which were not inexpensive. Revolutionaries usually knew how to dress. The man opposite him had the scarred visage of a movie actor who had fallen on hard times. Something about him seemed distantly familiar, which seemed a terrible thought.

“Behold, I will make a covenant.…”

“I heard you the first time,” Batisti sighed.

“What does it mean?”

The politician briefly closed his eyes. “The Bible?” he guessed, tiring of this game. “One of the Old Testament horrors, I imagine. Like Leviticus. I have no time for such devils, I’m afraid. Who needs them?”

The man reached down to retrieve something, then placed the object on the table. It was Batisti’s own laptop computer, which had sat next to him in the back of the official car.

“Cave eleven at Qumran. The Temple Scroll. Not quite the Old Testament, but in much the same vein.”

“It’s a long time since I was a professor,” Batisti confessed. “The Dead Sea was never my field. Nor rituals. About sacrifice or anything else.”

“I’m aware of your field of expertise.”

“I was no expert. I was a child, looking for knowledge. It could have been anything.”

“And then you left the university for politics. For power.”

Batisti shook his head. This was unfair, ridiculous. “What power? I spend my day trying to turn the tide a little in the way of justice, as I see it. I earn no more now than I did then. Had I written the books I wanted to …”

Great, swirling stories, popular novels of the ancients, of heroism and dark deeds. He would never get round to them. He understood that.

“It’s a long time since I spoke to an academic. You were a professor of ancient history. Greek and Roman?”

Batisti nodded. “A middling one. An overoptimistic decoder of impossible mysteries. Nothing more. You kidnap me, you shoot my

driver, in order to discuss history?”

The figure in black reached into his jacket and withdrew a short, bulky weapon. “A man with a gun may ask anything.”

Giovanni Batisti was astonished to discover that his fear was rapidly being consumed by a growing sense of outrage.

“I am a servant of the people. I have never sought to do anyone ill. I have voted and spoken against every policy, national and international, with which I disagree. My conscience is clear. Is yours?”

The man in black scowled. “You read too much Latin and too little English. ‘Thus conscience does make cowards of us all.’”

“I don’t imagine you brought me here to quote Shakespeare. What do you want?” Batisti demanded.

“In the first instance? I require the unlock code for this computer. After that, I wish to hear everything you know about the arrangements that will be made to guard the great gentlemen who are now in Rome to safeguard this glorious society of ours.” The man scratched his lank gray hair. “Or is that theirs? Excuse my ignorance. I’ve been out of things for a little while.”

The Garden of Angels

The Garden of Angels Solstice

Solstice Death in Seville

Death in Seville A Season for the Dead

A Season for the Dead The Killing tk-1

The Killing tk-1 The Savage Shore

The Savage Shore Dante's Numbers

Dante's Numbers Sacred Cut

Sacred Cut City of Fear nc-8

City of Fear nc-8 The Blue Demon

The Blue Demon The Garden of Evil

The Garden of Evil The Lizard's Bite

The Lizard's Bite The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Sleep Baby Sleep

Sleep Baby Sleep Lucifer's Shadow

Lucifer's Shadow Season for the Dead

Season for the Dead The Seventh Sacrament

The Seventh Sacrament The Garden of Evil nc-6

The Garden of Evil nc-6 Juliet & Romeo

Juliet & Romeo A Season for the Dead nc-1

A Season for the Dead nc-1 The Fallen Angel nc-9

The Fallen Angel nc-9 Little Sister

Little Sister The Lizard's Bite nc-4

The Lizard's Bite nc-4 The Killing 2

The Killing 2 The Fallen Angel

The Fallen Angel The Sacred Cut

The Sacred Cut Carnival for the Dead

Carnival for the Dead The Villa of Mysteries nc-2

The Villa of Mysteries nc-2 Macbeth

Macbeth The Killing - 01 - The Killing

The Killing - 01 - The Killing The Villa of Mysteries

The Villa of Mysteries Dante's Numbers nc-7

Dante's Numbers nc-7 The Sacred Cut nc-3

The Sacred Cut nc-3 The Seventh Sacrament nc-5

The Seventh Sacrament nc-5