- Home

- David Hewson

The Fallen Angel nc-9

The Fallen Angel nc-9 Read online

The Fallen Angel

( Nic Costa - 9 )

David Hewson

David Hewson

The Fallen Angel

PART ONE

ONE

It was the last Saturday of August, just past midnight. Nic Costa sat on a low semi-circular stone bench midway across the Garibaldi bridge, listening to the Tiber murmur beneath him like some ancient spirit grumbling about the noise and dirt of the city.

To his left in Trastevere ran a steady stream of cars and crowded late-night buses taking people home to the suburbs, workers from the hotels and restaurants, diners and drinkers too tired or impoverished to stay in the city any more. On the opposite side of the river, where this portion of the road bore the name Lungotevere de’ Cenci, the traffic flowed towards the centre, more quietly at this time of night.

Rome was slowly, reluctantly, working its way towards sleep. If he closed his eyes he could almost imagine himself at home in the countryside of the Appian Way, listening to nothing but the distant echo of insomniac owls. Then, from both sides of the river, came the familiar sound of the weekend: loud, slurring voices, English, German, American, some he couldn’t name. The many busy bars of Trastevere and the Campo dei Fiori were beginning to disgorge their customers onto the street and for the next few hours the uniformed police and Carabinieri who worked the graveyard shift would find themselves dealing with the aftermath of an alcohol culture that was utterly alien to them. Most Romans didn’t much like getting drunk. Excess of this nature was socially unacceptable, an embarrassment, though that night he’d had rather more wine than usual and didn’t regret it for a moment.

Further along the Tiber he could see a noisy bunch of young men and women stumbling across the ancient pedestrian bridge that joined Trastevere, near the Piazza Trilussa, with the centro storico. Costa wished he had the time and energy to walk there, then further still, until he could see the Castel Sant’Angelo illuminated like some squat stone drum left behind by the forgetful children of giants. Rome seemed magical, a fairy-tale city, on a drowsy evening such as this. And there were so many memories locked in these streets and lanes, the houses and churches and palaces around him. Good and bad, some fresh, some fading into the muted, resigned acceptance he had come to recognize as a sign of age.

‘May I ask again? What happened in Calabria?’ inquired the woman seated next to him.

There was nothing like a gelato in the open air after midnight. He was three days into his summer holiday, one forced on him by the state police’s insistent human resources department. Already he felt a little bored. Then along came unexpected company.

Costa licked his cone, bitter chocolate and fiery red pepper, thought for a moment and said, ‘It’s all been in the newspapers.’

‘The newspapers! Some of it. About you and Leo and the rest locking up a bunch of crooks and politicians then getting feted by Dario Sordi in the Quirinale Palace. Medals from the president of Italy.’

‘It was one medal,’ he pointed out. ‘A very small one.’

‘So why did you need a party to celebrate?’

It was a good question. He hadn’t. It was their colleagues in the Questura who’d arranged that evening’s private celebration at a famous restaurant near the Pantheon. It was there that, by accident, on his part at least, he had met the woman who was now by his side picking at a pistachio ice cream with mixed enthusiasm. Teresa Lupo had invited her without telling him, and winked at him like some old-fashioned comic as she arrived. He felt sure he’d blushed, and hoped no one had noticed. And then he’d scarcely talked to anyone else all evening.

‘It’s disconcerting,’ she continued. ‘I turn my back for one moment and suddenly everything’s changed.’

‘You’ve been gone for nearly two years, not a moment. Of course things are different.’

Her round brown eyes glittered beneath the single iron lamp above them.

‘So I see,’ she said. ‘I’d like to know what happened in Calabria. To Gianni and Teresa. To Leo.’ She hesitated. ‘To Nic Costa too. Him most of all.’

‘I laid to rest some ghosts,’ he said without thinking, and realized he was happy to hear those words escape his own lips. ‘Most of them really. But that’s a story for another time.’

She put her small hand on his arm and moved a little closer. He was unable to take his attention away from her dark, inquisitive face, which was even prettier than he remembered, bearing the signs of make-up and some personal attention which had never been there before.

‘I’m happy for you. Would you mind very much if. .?’

She took his arm and wound it around her shoulders. Then her head leaned against his and he felt her soft, curly black hair fall against his cheek.

He whispered, half to himself, ‘I remember the first time I saw you. It was in that little outpost of the Barberini where you kept your paintings. You were a nun.’

‘I was never a nun. I was a sister. I took simple vows, not solemn ones. How many times do I have to tell you this?’

‘Quite a lot, I imagine. Is that. . possible?’

He heard, and felt, her laughter.

‘I don’t see why not. I’ve only been back three weeks. There’s time. All the time in the world really.’

But there isn’t, Costa thought.

‘It was winter,’ he recalled. Bleak midwinter. The bleakest ever. He’d seen his wife, Emily, die before his eyes. That loss, and its cruel, invisible twin, the associated guilt over her murder, had almost broken his spirit. He’d wondered for a while if he would ever put that dark time behind him. It might have been impossible without this woman’s unexpected intervention. ‘You wore a long black shapeless dress with a crucifix round your neck. You carried your life around in plastic bags. There was nothing in your world except painting and the Church.’

‘Back then all of that was true.’

Emily’s loss still marked him, and always would. But it had become a familiar, background ache, a scar he had come to recognize and accept. The sight of her in those last moments, by the mausoleum of Augustus, in the grip of the man who would kill her, no longer haunted him. Time attenuated everything after a while.

Feeling a little giddy from the wine Falcone had ordered throughout the evening, he took away his arm, turned and peered into Agata’s eyes. She was still the woman he’d first met. Someone with the same intense curiosity, one which so often creased her high forehead with doubts and questions that this habit of fierce concentration had, with age, left the faintest of marks there, like scars of the intellect.

‘The last time we met was at the airport. You were going to Malta to work for some humanitarian organization. You weren’t a nun or a sister or whatever any more. Your life still seemed to be contained in plastic bags. You didn’t have art. I wasn’t sure you had the Church.’

‘You sound as if you were worried.’

‘Of course I was! You’d spent your entire life in a convent. You were going somewhere you didn’t know. To a life you didn’t understand.’

She folded her arms and glowered at him.

‘You’d lost your wife. And you were worried about me? Someone you barely knew? This constant selflessness of yours is ridiculous, Nic. You can’t worry about everyone. You have to lose that habit.’

‘I have lost it. As much as I want to, anyway.’

‘Well done. I didn’t abandon painting by the way. Or the Church either. The first is your fault. You told me to go and see that Caravaggio in the Co-Cathedral in Valletta. The Beheading of St John the Baptist.’

She edged further into his arms and placed her head on his shoulder.

‘Sorry,’ he said. ‘It’s good, isn’t it?’

‘It’s a depiction of a man

who’s just been executed. His murderer is reaching down to finish the job with a very small knife.’ She hesitated. ‘It’s wonderful. I refused to go and see it for nearly eighteen months. When I went I took one look and knew I couldn’t stay out of the world forever. It’s like every other Caravaggio I’ve ever seen: a call to life. A challenge, to face our fears.’

‘And the Church?’ he asked.

‘I’m still a good Catholic. I simply came to understand there are more definitions of the word “good” than I’d learned inside a convent. Also I missed Rome. .’ She closed her eyes. ‘. . so very much.’ She smiled and looked back at the city, now growing somnolent beneath the clear night sky. ‘I grew up here. This place is my life. I couldn’t leave it forever. Could you?’

‘Never. This job of yours. .’ He still struggled with the idea of her earning a living like everyone else. ‘How did you get it?’

‘Hard work! How else? I didn’t sit in my cell all day, you know. I have the degree, the postgraduate qualifications, to teach the history of art anywhere in the world. Why do you think those eminent men from the Palazzo Barberini used to come to me for an opinion?’

‘Because they valued it,’ he said quickly.

‘Quite. On Monday I become assistant professor at the Raffaello College in the Corso. It’s a school for foreign students. Not a public university exactly. Perhaps that will come later. But it’s a job, the first I’ve ever had. Teaching spoilt brats the history of art. Caravaggio in particular. You, however, may attend my lectures for free.’

‘I will.’

‘No. I was joking. You know as much as I do about him. More in some ways. You can see into his head. I never will. Frankly I don’t want to.’

Her hand went to his hair. She stroked his head, as if amazed by their closeness.

‘Those ghosts really are gone, aren’t they?’ Agata Graziano whispered.

‘Exorcized,’ he said.

‘Don’t tell me what buried them. I don’t want to know. It’s enough that they’re dead.’

TWO

Costa felt awkward holding her. He still had a gelato in one hand, as did she, and it seemed inevitable that this experimental moment would culminate in a kiss. He was happy with this idea, provided the evening ended there. He needed to think about Agata’s sudden reappearance in Rome a little more. In the morning, when his head was clearer, and hers too.

She noticed his predicament with the ice cream, raised a single dark eyebrow, and nodded at the ground.

‘No,’ he said. ‘We’ve enough litter in Rome as it is.’

He got to his feet, took the half-finished cone from her fingers, went to the bin at the end of the bench and deposited both ice creams there.

When he got back she was standing up, a diminutive and beautiful young woman with her arms folded across her chest. She wore a tight dark jacket, a scarlet silk shirt and grey slacks. Around her neck was a silver chain with some abstract ornament — not a cross — that he’d noticed earlier. Her dusky, compact face was stiff with a familiar bemused anger. The noise of the revellers finding their way home from the Campo and Trastevere was getting louder all the time. Bellowed shouts and obscenities in foreign languages. This was the price of being an international city.

‘Perhaps not all the ghosts have gone,’ Agata said. ‘I wonder. .’

‘Enough talking,’ Costa said, then took her in his arms and kissed her, chastely almost, on the lips, holding her very gently so that she could withdraw easily from his grip.

He imagined this was the first time any man had embraced Agata Graziano, not that he had much idea of what she’d done in Malta for the last two years.

They broke for breath. Since they’d last met scarcely a day had passed when he hadn’t thought about the curious little sister from the convent in the centro storico who had fought so bravely to find some justice for him after the efforts of the police and the judiciary had failed.

To his astonishment her eyes stayed wide open throughout.

‘I’m sorry,’ Costa said quickly.

‘No, no, no. . don’t apologize.’

‘I didn’t mean. . I thought. .’

She waited, then said, ‘Thought what?’

‘I thought that perhaps you wanted me to. .’

Before he’d finished she dashed forward, kissed him quickly and rather roughly on the lips, then pulled back grinning, looking a little wild.

‘I did. And I like this!’ Agata announced brightly before lunging at him once more.

The kiss was brief, the embrace longer. She stayed in his arms, smiling, her head against his chest.

‘I like this a lot,’ she murmured. ‘Nic. .’

She glanced up at him. At that moment, from somewhere in the network of streets on the city side of the bridge, there was a cry, that of a man in terrible pain. Then, not long after, came a young female voice calling, shouting, words that were so high-pitched and full of distress they were incomprehensible.

‘You can’t take your car home,’ Agata declared, trying to ignore the din. ‘You’ve had too much to drink. A taxi driver will charge the earth to take you out to that beautiful house in the country. My job comes with a little apartment.’ She hiccupped, out of embarrassment perhaps. ‘In the Via Governo Vecchio, believe it or not. Please. .’

He shuffled from side to side and stared at his feet. He hadn’t been driving a car lately. At the beginning of the month, when the city began to wind down, he’d decided to resurrect his father’s ancient Vespa scooter from the garage. With the spare time from his holiday he’d got it back on the road. The thing was parsimonious with fuel and it was wonderful to feel the fresh air against your face in weather like this, dodging the traffic, parking anywhere. The Vespa was a little rusty in places but the engine still had noisy fire in its little belly. Now the decrepit little turquoise beast was just round the corner, waiting in a side street.

The racket from across the road kept getting louder and louder.

‘In my apartment I have a. .’ She struggled for the words as her skin took on the warmth of a rising blush. ‘A. .’

‘A couch?’

‘I have a bed.’ Agata blinked at him, wobbling a little. ‘There. I’ve said it.’ She smiled, a little bashful, perhaps even a little ashamed. ‘You’re happy, just like Teresa said you’d be. Finally. The Nic I always knew was there even when I could see your heart was breaking. My Nic. .’

‘You’re babbling,’ he said, reaching forward and taking her shoulders. ‘Do you have a couch?’

‘I am not babbling. Of course I’ve got a stupid couch. I live in the Via Governo Vecchio.’

‘Good. Then. .’

The unseen girl was screaming again, at the top of her voice. There was real agony and fear in her cries, not the drunkenness and violence he’d come to recognize over the years. He could see his concern reflected in Agata’s shocked features.

‘There’s something wrong,’ she said, her eyes wide and glassy with trepidation.

‘Stay here, please,’ Costa ordered.

Then he ran across the riverside road and down towards the tortuous web of lanes and alleys that meandered in every direction out from the ghetto like a tangle of veins and arteries wound around the human heart.

THREE

The commotion was in the first street on the right after he crossed the Lungotevere de’ Cenci. In the half light of a single street lamp he could see a body lying on the ground, legs apart in a broken, unnatural fashion, the upper torso in darkness at the foot of a tall residential building.

Something was next to the figure, a pale shadow in what looked like child’s pyjamas, faint pink. This was the source of the keening, wailing scream that had brought him here.

He took out his phone, called the control room, identified himself and ordered an emergency medical crew.

‘We’ve had a call already,’ the operator told him. ‘Didn’t leave a name. Do you know what happened?’

‘No, but someone’s

hurt.’

‘Need anything else?’

The figure in the pyjamas fluttered out into the light like a moth struggling to break free of a spider’s web. It was a girl, Costa thought immediately, and there was blood on her, on her chest, and in the loose, flapping fabric around her legs.

‘Make sure there’s some backup,’ he said, without quite knowing why. This was a complex, rambling part of town, on the very edge of the ghetto. There were people closing in, attracted by the noise. No blue flashing lights. Not a sign of a uniform, police or Carabinieri.

He was off duty, unprepared, a little heady from Falcone’s wine. But there was no one else around.

Crossing the street he called out, ‘Signora.’ Then looked more closely as he approached, saw her fully in the light, crying, distressed, quite beside herself, blood sticking in a messy smear across her slender chest and thighs.

‘Signorina,’ Costa corrected himself as he approached. ‘Police.’

He reached her, stopped, a little breathless. The girl was perhaps fifteen or sixteen. Her long blonde hair was the colour of old gold under the lamps and hung in thick tresses around her shoulders as she twisted and turned, trying to see what was around them, glancing anxiously at the shape on the ground. She had a beautiful, pale, northern European face, trapped between womanhood and the world of a child, innocent yet on the verge of knowledge.

There was a strange noise from somewhere nearby, like the trickle of water or sand.

‘Daddy,’ she mumbled in English, looking at the stricken body on the ground.

‘Signorina. .’ Costa took her skinny bare arms and held her. This was odd. There was still the sharp sense of danger somewhere close by. ‘Tell me what happened.’

She looked into his eyes and he found himself lost for a moment.

‘He fell,’ the girl said simply and glanced at the building behind them.

Costa looked at the figure on the black Roman cobblestones. After a decade in the force the rules came back without a second thought. Protect the living, protect yourself. Then, and only then, think of the dead. And this man was gone. He could see it, in the shattered skull, so broken he didn’t want to peer too closely, and the unnatural, agonized way the corpse was sprawled on the hard ground.

The Garden of Angels

The Garden of Angels Solstice

Solstice Death in Seville

Death in Seville A Season for the Dead

A Season for the Dead The Killing tk-1

The Killing tk-1 The Savage Shore

The Savage Shore Dante's Numbers

Dante's Numbers Sacred Cut

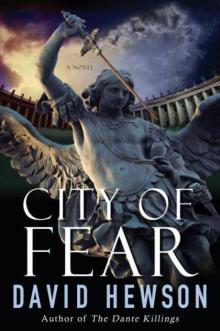

Sacred Cut City of Fear nc-8

City of Fear nc-8 The Blue Demon

The Blue Demon The Garden of Evil

The Garden of Evil The Lizard's Bite

The Lizard's Bite The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Sleep Baby Sleep

Sleep Baby Sleep Lucifer's Shadow

Lucifer's Shadow Season for the Dead

Season for the Dead The Seventh Sacrament

The Seventh Sacrament The Garden of Evil nc-6

The Garden of Evil nc-6 Juliet & Romeo

Juliet & Romeo A Season for the Dead nc-1

A Season for the Dead nc-1 The Fallen Angel nc-9

The Fallen Angel nc-9 Little Sister

Little Sister The Lizard's Bite nc-4

The Lizard's Bite nc-4 The Killing 2

The Killing 2 The Fallen Angel

The Fallen Angel The Sacred Cut

The Sacred Cut Carnival for the Dead

Carnival for the Dead The Villa of Mysteries nc-2

The Villa of Mysteries nc-2 Macbeth

Macbeth The Killing - 01 - The Killing

The Killing - 01 - The Killing The Villa of Mysteries

The Villa of Mysteries Dante's Numbers nc-7

Dante's Numbers nc-7 The Sacred Cut nc-3

The Sacred Cut nc-3 The Seventh Sacrament nc-5

The Seventh Sacrament nc-5