- Home

- David Hewson

The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Read online

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

The Killing

The Killing II

The Killing III

Carnival for the Dead

The House of Dolls

1

There was something new on the front deck of the houseboat. Standing tall amid the dead plants, rotting timber and scattered tools, she rose like a glittering beacon over the winter-grey waters of the Prinsengracht: a life-size silver plastic ballerina twirling on slender legs, twinkling coloured lights and tinsel round her neck.

Pieter Vos’s little terrier Sam sat at the statue’s feet wondering whether to growl or lick the thing. He had a string of multicoloured tinsel wound through his collar over the tight, tough fur. And didn’t much like it.

The third Sunday of November. Christmas was around the corner, and Sinterklaas was on his way. He’d already finished the long journey from Spain and boarded his ceremonial barge up the Amstel river. It was two fifteen.

Vos, as a duty brigadier for the second shift of the day, would have familiar company for this welcome interlude in the calendar of the Amsterdam police. Two of his plain-clothes officers of different sometimes conflicting generations. Dirk Van der Berg, the easy-going, beer-loving detective, a Marnixstraat fixture in his mid-forties, was patting the little dog, cooing affectionate words. Laura Bakker, just turned twenty-five, a recent newcomer from Friesland, stood in a heavy winter coat, long red hair falling round her shoulders, glaring at the object in the bows. Vos glanced at his own clothes: the usual navy donkey jacket, fading jeans, ageing trainers. He’d meant to have his hair cut during the week but went to see a Danish movie instead. So the curly dark locks still hung loose over his collar and got him a filthy look from Frank de Groot, the station commissaris, from time to time.

It was seven months now since a curious murder case centred round a museum doll’s house had dragged him out of a dreary, lost existence in his houseboat, back into the Amsterdam police. Some things had changed since then. A few hadn’t.

‘What in God’s name’s that?’ Bakker asked.

‘I like it!’ Van der Berg declared before the argument could begin. ‘Whatever it is . . .’

Bakker clumped down the gangplank in her heavy boots, pulled a white envelope out of the postbox without asking, then thrust the letter at Vos. It bore the stamp of the city council.

‘I bet this is another warning about the state of this thing. They’ll fine you if you don’t fix it up properly.’

‘I am fixing it up . . .’

She looked at the blackened, broken cabin, the windows held together by tape and shook her head.

‘They were throwing her out from one of the shops round the corner,’ Vos added, pointing at the ballerina. ‘I thought she sort of fitted.’

‘She does,’ Van der Berg declared. He glanced hopefully across the road at the Drie Vaten cafe on the corner of Elandsgracht. Vos’s local was the neighbourhood brown bar, black brick exterior, bare plank floor, rickety seats, open most of the day and busy already. The place the neighbourhood gravitated to when it needed good beer, a snack, a coffee and some idle conversation. A second home for plenty of locals, among them thirsty police officers from their Marnixstraat headquarters at the top of Elandsgracht. ‘Is there time for . . . ?’

‘We’re on duty!’ Bakker said, throwing up her long arms in despair.

Van der Berg was a heavyset man with a friendly, somewhat battered face. He looked offended.

‘We don’t go on duty for another fifteen minutes. I was about to say . . . is there time for a coffee?’

‘Not really,’ Vos said with a shake of his head.

A busy but agreeable day ahead. Sinterklaas, a beaming, friendly saint with a white beard, was set to mark his arrival in Amsterdam with a parade so celebrated it would be watched live on television throughout the Netherlands. Today the crowds would run into three hundred thousand or more, and the police presence would top four figures. The city centre was closed to all traffic as a golden barge bore Sinterklaas down the Amstel river, surrounded by a throng of private boats full of families trying to get close. Then he’d transfer to a white stallion for a procession through the city, ending at Leidseplein. There, welcomed by the mayor, he’d address the massed crowds from the balcony of the municipal theatre. Zwarte Pieten, Black Petes, companions to Saint Nicholas, would follow him everywhere, faces dark with make-up, curly black wigs, ruby lips, grinning in medieval costumes with ruff collars and feathered mob caps, handing out spicy sweets to every passing youngster they could find – and baffling foreign visitors who could scarcely believe their eyes.

After 5 December Sinterklaas gave way to Christmas. The pepernoot and chocolate letters were replaced with kerststol and musketkrans while the shop windows filled with pine boughs and fake snow.

There’d been a time when Vos was a part of all this. When he’d had a family of his own. A partner, Liesbeth, a daughter Anneliese. The doll’s house case had stolen that from him completely.

Vos bent down and smiled at his little dog. The white and tan fox terrier looked up into his face.

‘Can’t take you to work, old chap. Even on a day like this.’

Sam detected something in the tone of his voice and narrowed his eyes, suspicious of what was to come.

The lead came out. Sam’s head went down. Vos walked the dog to the cafe, handed him over along with a bag of dirty washing, another favour from the Drie Vaten’s owner, Sofia Albers. He tugged on the lead, struggling to return to the canal.

Van der Berg and Laura Bakker watched in silence. Bakker was shaking her head again.

‘Well!’ Vos said when he was back at the boat. ‘Let’s go mingle. Tell you what . . . after the shift I’ll treat you both to dinner. I know an all-night place.’

‘You mean beer, crisps and free boiled eggs?’ Bakker asked.

‘No . . . real dinner. A restaurant.’

‘Somewhere they have a proper toilet? You know such places? Honestly?’

‘So long as it involves . . .’ Van der Berg’s hand made a glugging motion. ‘That’s fine with me. Oh dear . . .’

He pointed at the sleepy bar, its black brick frontage set at an angle where Elandsgracht met the canal. Gulls were scavenging the rubbish on the cobbles. A couple of afternoon drunks queued patiently to drop their empty bottles in the glass bin. Next to them Sam was digging in his heels, refusing to go inside, and glaring back at the canal with an expression of heartfelt canine resentment.

‘Shame we can’t take him with us,’ Bakker suggested. ‘I mean . . . it’s Sinterklaas. It’s not as if anything bad’s going to happen.’

Vos stared at her, said nothing, went to the dog and led him inside by the collar.

Then came out and looked down the length of Prinsengracht.

‘Don’t you read the papers?’ Van der Berg asked. ‘They said there might be a protest about Zwarte Piet. People think it’s racist or something. Disrespectful.’

One of them was marching up their side of Prinsengracht as he spoke. Tall, burly with a huge Afro wig, all exaggerated curls. Shiny scarlet costume, silly hat. Blackened face, ruby lips. Beaming, happy as a child, carrying a brown bag and a long-handled fishing net to reach the crowds.

‘It is disrespectful,’ Bakker complained. ‘This is the twenty-first century for pity’s sake.’

Van der Berg folded his arms and started on the lecture Vos had heard so many times. The other side of the argument.

‘It’s tradition,’ he concluded.

‘So was hanging. And bear-baiting.’

‘Young lady . . .’

Vos closed his eyes, unable to think of a single

phrase more calculated to infuriate the bright and awkward detective from Friesland.

Then the Black Pete heard the commotion, spotted her, scuttled across the cobbles, bowed graciously, said how pretty she looked, placed a handful of small biscuits in his fishing net and gingerly extended them towards her.

Bakker stopped mid-rant, grinned and took a few. Preened herself as the man in the bright costume paid her more compliments.

‘Now you be a good girl,’ he added as he wandered off down the street. ‘Or Sinterklaas will know.’

‘I love these things,’ she said, stuffing a spicy pepernoot into her mouth with a half-guilty giggle.

‘So do I,’ Van der Berg told her, eyeing the two left in her hand.

Bakker ignored him.

‘Where do you stand, then?’ she asked turning her steady gaze on Vos. ‘When it comes to grown men blacking up for Sinterklaas?’ She nodded at Van der Berg. ‘With him? Or me?’

Sam was at the window of the bar, one paw scratching at the pane, wagging his tail in forlorn hope.

‘Out with it,’ Bakker added.

‘I think,’ Vos answered, watching the Black Pete skip merrily up the canal, ‘it’s time we went to work.’

Another Black Pete, short this time and tubby. Ginger beard sticky with black make-up. The wig was on sideways, too shiny, brand new. Scared eyes looking everywhere as he listened to the growing racket of the crowd shuffling down the street.

The stuff was where they said they’d leave it, in the third rubbish skip from the back of a narrow dead-end alley. A blue one, just like they said.

Two handguns. Two knives. Three grenades. A length of rope. Some pieces of fabric that could double as gags or blindfolds. Five thousand euros in a bundle and a counterfeit Belgian passport with the photo taken in a booth at Centraal station two days before.

A single sheet of paper with lines of printed instructions. What to do. What to look out for. Where to go.

Born in the north of England. Radicalized after a spell in prison for a drunken burglary. When he came out he grew a scrappy beard, put on the long robe. Yelled at funeral processions for dead soldiers killed in Afghanistan. Went to the right preachers. Learned how to bellow slogans while he stabbed at a camera with his forefinger.

After he changed his name to Mujahied Bouali even his mother, a nurse, widowed when he was four years old, ceased to want to know him. Which was fine. He did what he was told, and finally the call came. Not Syria or Somalia as he expected. But Amsterdam, under the wing of a new master. A stern and autocratic man who drilled into him something he’d known for a while but never wanted to face.

They were all his enemies now. Every unbeliever. There was no middle ground. No such thing as a civilian. The decadent unthinking herds sat back and watched as the world fell to pieces.

There were the righteous and the damned. Nothing in between.

Alongside the money was a photo of a young girl in a pink jacket. A fresh page of instructions to be memorized then disposed of.

He read them carefully, took a good look at the picture. It looked as if it had been snatched furtively in the street. He wondered for a moment what her name was. Then realized it didn’t matter.

After that he placed the guns, the knives, the rope, the lengths of fabric and the grenades inside his red velvet bag alongside the sweets.

Christian sweets. But food knew no faith.

He picked one out, tasted it. Good, he thought. And that was probably down to the spices they stole from the east.

Bag slung round his shoulder he walked out into the street. The costume they’d given him was bright green, too loose, with a brown beret topped with a bright-pink feather.

Any other time he’d have felt a fool. Not now.

The Kuyper house was ten minutes by bike from Vos’s houseboat, in a busier, more affluent quarter of the city beyond the Jordaan. Four centuries old, narrow, with four floors beneath a tiny crow-stepped gable, it stood on the street called the Herenmarkt to the side of the West-Indisch Huis, once headquarters to the Dutch West India Company. The location always amused Henk Kuyper. In the courtyard of the grand mansion was a statue of Peter Stuyvesant, seventeenth-century governor of the Dutch state called New Netherlands. The aristocrat who lost the colony to the British, handing over the tip of Manhattan he called New Amsterdam only to see it rechristened New York.

Between sessions on the computer and web chats with his many contacts across the world, Kuyper would sometimes walk down into the little square and take a coffee there, stare at the grim features of the man who gave away the New World’s most important foothold and wonder what he’d make of the twenty-first century. Stuyvesant’s early fortifications in America were now Wall Street; his canal became Broad Street and Broadway. The man they called ‘Old Silver Leg’ for his prosthetic limb lay buried in the vault of a church in Manhattan’s Bowery – once his bouwerij, a farm – on the site of the former family chapel. Kuyper had wandered there during the Occupy Wall Street protests and camped nearby for a while. He’d stared at the plain stone plaque in the west wall that marked the old man’s resting place, thinking about the distance from there to here.

Yet for most of the citizens of the twenty-first century Peter Stuyvesant was nothing more than a brand of cigarette. Such was history.

‘Henk!’ His wife’s voice rose from the floor below, shrill and anxious. She always struggled with occasions. ‘We’re ready. Are you coming or not?’

‘Not,’ he whispered to the busy screen.

Sunday and the contacts never ended. There were seven emails in his inbox. Two from The Hague. Two from America. Three from the Middle East.

He heard her stomping up the stairs. Kuyper’s office was in the building’s gable roof beneath the crow steps. Tiny with a view out onto the cobbled street and the children’s playground that occupied the open space behind the West-Indisch Huis. The pulley winch above the windows was principally decorative now, but it had probably sat there for three centuries at least. He liked this room. It was private, cut off from the rest of the house. A place he could think.

‘Are . . . you . . . coming . . . ?’

She stood in the doorway wearing a too-short winter coat, hand on the lintel, Saskia by her side. Renata Kuyper was Belgian, from Bruges. They met when he was on a mission to Kosovo one scorching summer. She was a student on a research project, pretty with short brunette hair and an animated, nervy manner. It was a brief and passionate courtship conducted in hot hotel rooms that smelled of cedar wood and her scent. Outside the Balkan world was slowly rebuilding itself from the nightmare of civil war.

Henk Kuyper barely noticed. They were in love, desperately so. Then, in the middle of that frantic summer, her widowed father died suddenly. The news came in a phone call while they were in bed. After that she clung to Henk. Within the space of three months they were married. Another three months back in Amsterdam, Renata pregnant, trying to come to terms with the idea of being a wife and mother in a bustling, unfamiliar city where she had no friends.

‘Are you coming, Daddy?’ Saskia repeated.

Eight years old, nine in January. Pretty much the picture of her mother. Narrow pale face. High cheekbones. Blonde hair that would one day turn brunette like Renata’s. Eyes as blue and sharp as sapphires. Didn’t smile so much which was like her mother too. But that was the family now.

‘Thing is, darling . . .’ He got up from the desk and crouched in front of her, touched her carefully brushed hair. It was important to look your best when you met Sinterklaas and his little black imps. ‘Daddy’s got work to do.’

On paper Kuyper was a consultant in environmental affairs. His speciality was ground pollution issues, a subject he’d studied at university. Sometimes in person, he travelled to assignments mostly in Third World countries, a few of them perilous. But that was just a job. Words to put on a business card. He spent at least half his time anonymous on the Net, offering advice in activist forums on everything from frack

ing to biofuels and genetically modified crops. Attacking those in industry and on the right. Starting bush fires in some places. Putting them out in others. Always under the same anonymous online identity, one he’d picked deliberately: Stuyvesant. He even used a portrait of the old man as his avatar.

Saskia came up to him at the desk, a big pout on her face.

‘Don’t you want to see Sinterklaas at all?’

He just smiled.

She started to count on her gloved fingers.

‘You missed him on the boat. You missed him when he was riding his horse . . .’

His wife was staring at him.

‘You can stop saving the world, Henk. For one day. Be with your family.’

Kuyper pushed back his glasses and sighed. Then pointed at the computer.

‘Besides . . . you know I’m not good with all those people around. Crowds . . .’ He touched his daughter’s cheek. ‘Daddy doesn’t like them.’

The little girl stamped her feet and wrapped her skinny arms around herself, tight against the bright-pink jacket he’d bought her the week before. My Little Pony. Her favourite from the books and the TV. He reached out and squeezed her elbow.

‘Sinterklaas came early and brought you that, didn’t he?’

‘No.’ The pout got bigger. ‘You did.’

‘Maybe I’m Black Pete. In disguise.’ He gestured at the door. ‘Go on. Tonight we can have pizza. I’ll make it up. Promise.’

He listened as they made their way down the narrow staircase. One set of footsteps heavy, one light. Then he rolled his chair to the window and looked out into the street. His wife was pushing the expensive cargo trike he’d bought them. Orange. The colour of the Netherlands. She climbed on the saddle. Saskia parked herself in the cushioned kid’s area at the front she called the ‘bucket’.

His phone went. The call didn’t take more than a minute.

Across the road he saw his first Black Pete. There’d be hundreds roaming the city, baffling every foreigner who stumbled upon them. Anyone could hire the costume, find some make-up and scarlet lipstick. Put on the stupid wig, the frilly jacket, the colourful trousers, the gold earrings. Then buy a bag of sweets from a local shop and hand them out to anyone they felt like.

The Garden of Angels

The Garden of Angels Solstice

Solstice Death in Seville

Death in Seville A Season for the Dead

A Season for the Dead The Killing tk-1

The Killing tk-1 The Savage Shore

The Savage Shore Dante's Numbers

Dante's Numbers Sacred Cut

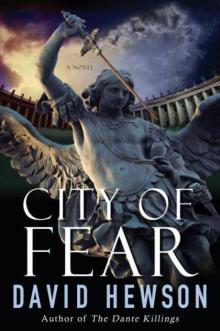

Sacred Cut City of Fear nc-8

City of Fear nc-8 The Blue Demon

The Blue Demon The Garden of Evil

The Garden of Evil The Lizard's Bite

The Lizard's Bite The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Sleep Baby Sleep

Sleep Baby Sleep Lucifer's Shadow

Lucifer's Shadow Season for the Dead

Season for the Dead The Seventh Sacrament

The Seventh Sacrament The Garden of Evil nc-6

The Garden of Evil nc-6 Juliet & Romeo

Juliet & Romeo A Season for the Dead nc-1

A Season for the Dead nc-1 The Fallen Angel nc-9

The Fallen Angel nc-9 Little Sister

Little Sister The Lizard's Bite nc-4

The Lizard's Bite nc-4 The Killing 2

The Killing 2 The Fallen Angel

The Fallen Angel The Sacred Cut

The Sacred Cut Carnival for the Dead

Carnival for the Dead The Villa of Mysteries nc-2

The Villa of Mysteries nc-2 Macbeth

Macbeth The Killing - 01 - The Killing

The Killing - 01 - The Killing The Villa of Mysteries

The Villa of Mysteries Dante's Numbers nc-7

Dante's Numbers nc-7 The Sacred Cut nc-3

The Sacred Cut nc-3 The Seventh Sacrament nc-5

The Seventh Sacrament nc-5