- Home

- David Hewson

The Savage Shore

The Savage Shore Read online

Contents

Cover

Recent Titles by David Hewson

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Part One: Martinis for a Marmoset

Part Two: The Wine-Dark Sea

Part Three: The Fist of Rock

Part Four: A Time to Kill

Part Five: The Sicilians

Part Six: The Grave of Carcagnosso

Part Seven: A Momentary Music

Author’s Note

Recent Titles by David Hewson

The Nic Costa Series

A SEASON FOR THE DEAD **

THE VILLA OF MYSTERIES **

THE SACRED CUT **

THE LIZARD’S BITE

THE SEVENTH SACRAMENT

THE GARDEN OF EVIL

DANTE’S NUMBERS

THE BLUE DEMON

THE FALLEN ANGEL

THE SAVAGE SHORE *

Other Novels

CARNIVAL OF DEATH

THE FLOOD *

JULIET AND ROMEO

* available from Severn House

** available in eBook format from Severn House

THE SAVAGE SHORE

David Hewson

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

First published in Great Britain and the USA 2018 by

Crème de la Crime, an imprint of

SEVERN HOUSE PUBLISHERS LTD of

Eardley House, 4 Uxbridge Street, London W8 7SY

This eBook edition first published in 2018 by Severn House Digital

an imprint of Severn House Publishers Limited

Trade paperback edition first published

in Great Britain and the USA 2018 by

SEVERN HOUSE PUBLISHERS LTD

Copyright © 2018 by David Hewson.

The right of David Hewson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

ISBN-13: 978-1-78029-106-2 (cased)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78029-588-6 (trade paper)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78010-993-0 (e-book)

Except where actual historical events and characters are being described for the storyline of this novel, all situations in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to living persons is purely coincidental.

This ebook produced by

Palimpsest Book Production Limited,

Falkirk, Stirlingshire, Scotland

If justice is taken away then what are states but gangs of robbers? And what are gangs of robbers themselves but little states?

St Augustine, The City of God

PART ONE

Martinis for a Marmoset

Extract from Calabrian Tales, by Constantino Bergamotti

(1898-1955)

first published 1949

Chapter IV: The Garduña

In the eighth century, when the Moors ruled much of the Iberian peninsula, there was a priest named Apollinario, a hermit who lived in a cave in the hills above Córdoba. One day the Virgin Mary came to him in a dream and declared that he was destined to be the saviour of his native Spain, forming an army to drive the Muslims from God’s beloved Catholic nation.

Flattered as he felt by this divine revelation, Apollinario was reluctant to take on such a task. He was a priest not a soldier, let alone a general. The Moors were everywhere. They were for the most part benign rulers, willing to tolerate those of other faiths, builders of great mosques and libraries, creators of a rich and philanthropic civilisation. How could one unworldly priest fight such a power? And with what?

Seeing his doubts the Virgin reached out and gave him a silver bracelet from her wrist. When Apollinario touched this precious item he knew that her strength, which came directly from God, now lay within him. In this way began the Garduña, Apollinario’s sacred army, warriors of the night, fighters determined to rid Europe of Muslim domination.

With the private blessing of the Church, this band of holy villains grew to thousands, all of them sworn to destroy the followers of Allah, not through bloody confrontation on the battlefield, but by stealth and treachery and theft, the stiletto in the dark, the artistry of tricksters, every criminal device available, since the Arabs, being heathen, merited neither mercy nor forgiveness. Over the centuries the Garduña quietly gathered like-minded men to their cause, honing their skills as assassins and vagabonds, murdering, raping, robbing, and pillaging, slaying Muslims, Jews, and any Christians who opposed them, before seeking, and gaining, forgiveness for their sins.

Around 1670 the Inquisition, which had used their talents to such effect, began to turn on its loyal servants, seeing them as a pernicious criminal element that threatened the Vatican’s own temporal power. Throughout Spain thousands of loyal members were arrested, many executed, the rest stripped of homes and possessions, thrown into dank prisons, their families left to starve in destitution. Those of Apollinario’s children who remained fled into the hills whence they came, hiding their identities, surviving as best they could by virtue of the only talents they knew.

Three of the boldest, Catalan brothers Osso, Mastrosso and Carcagnosso, found themselves trapped in the city of Barcelona, with the king’s men standing between them and their mountain home, knowing they were the greatest prize of all since they had in their possession Apollinario’s precious silver bracelet given to him by the Virgin. Outflanking the soldiers of the Inquisition in the dead of night, they stole a flimsy fisherman’s dory from the harbour and cast themselves upon the mercy of the waves. This was in November of 1673, at the beginning of a vicious winter that straddled the length of the Mediterranean, one which would witness the sea freeze in Siracusa, beggars die of bitter cold in the grand avenues of Alexandria, and snow cover the Temple Mount in Jerusalem for weeks on end.

The brothers fought to control their little boat on the wild waters of the Balearic, hoping to reach Mallorca and safety in Palma, where some of their Garduña brothers had found sanctuary. They were God’s thieves, not sailors, and knew nothing of navigation or seafaring. So fierce was the storm that their flimsy boat was tossed about like flotsam for eight long days and nights. These young men grew weak and confused, fearing their lives would be lost on the cold grey ocean, each in turn clutching Mary’s holy bracelet to his chest, praying for deliverance.

Perhaps the Virgin was listening, even through the tempest. Starving and close to madness, finally they found themselves beached in Sardinia, near to the city of Cagliari, stranded in a nation which spoke their native Catalan and was, in law at least, still beholden to the kingdom of Castile.

Yet this was not true Spain. They were on the borders of the east, close to a mythical world of pirates and bandits, thieves and ruffians, the Hinder Sea of the Jews, the Mesogeios of Homer, the Mare Nostrum, following in the footsteps of so many others like them, the Vikings and the Normans, the Turks and the Saracens. And the greatest brigands of all, the Romans.

On this foreign soil these three brothers rediscovered themselves as a new Garduña, lying, cheating and stealing now from the wealthy and barbaric Sardinian lords. Their fortunes rose. Their stock improved. Soon they came to see that one island was too small to e

ncompass three such ambitious and talented men. With many tears and embraces, each knowing that separation was the only alternative to division and death, they bade each other farewell and set off to establish their individual fortunes, Mastrosso to Naples, Osso to Sicily, and Carcagnosso to Reggio at the tip of Italy’s toe in Calabria.

Here is the history of the south, Garibaldi’s Mezzogiorno, written with the blood spilled by these three brothers from Spain and those who came after. In Naples, Mastrosso began the brotherhood that came to be known as the Camorra, the name coming from capo morra, meaning boss of the crooked street game by which the innocent are fleeced of their wages. Not that alley tricks for a pittance were the Camorra’s principal interests for long.

In Palermo, Osso took a similar path, his creation coming to bear the name Cosa Nostra or Mafia, the origins of which are challenged by many, and perhaps impossible to pin down. The third brother, Carcagnosso, made the longest, hardest journey of all, to the bare, bleak land at the foot of Aspromonte, the last remaining fragment of ancient Greece in Italy. With his sons he came to form the ’Ndrangheta and here the etymology is clear: the Greek andragathia, meaning ‘those who are full of a strong goodness’.

It is natural that they should choose the ancient tongue of the eastern Mediterranean to describe themselves. Calabria is but the modern face of Magna Graecia, ‘Greater Greece’. The language of Aristotle and Demosthenes remains more audible in our local dialects than in the demotic Greek heard today on the other side of the Ionian.

‘Ndrangheta.

Strange, impenetrable, unpronounceable, fearsome. The name of ‘the honourable men’ seemed made for the sons of Carcagnosso as they seized Calabria, populating its inhospitable mountain ranges, its primitive ports and fishing harbours, bringing a kind of society, of civilisation, to an impoverished and neglected hinterland about which Rome and Florence and Milan cared nothing.

While the Mafia grew greedy and sought fame and riches in America, while the Camorra quarrelled, turned corrupt and untrustworthy, the ’Ndrangheta alone remained true to the Garduña, the sum of their fathers, nothing more, nothing less, their blood running pure from generation to generation.

The crones in the mountains say that somewhere in the bare, cold hills of Aspromonte may be found a grotto containing the silver bracelet of the Virgin Mary, given to the timid monk Apollinario somewhere outside Córdoba in a distant era when Andalusia rang to the cry of the muezzin, not the plainchant of the Holy Church. And by the altar in this hidden lair lies the tomb of his loyal follower, Carcagnosso.

A fairy tale for children? This is possible, so perhaps it has no part in history. What remains undeniable is this: only in Calabria does the spirit of the Garduña live on among ‘the honourable men’. They serve still, strong in their silence, asking nothing more than loyalty, obedience and their due, infected, like the Greeks before them, by the spirit of the land, which is wild and free, invincible even to time itself.

At three o’clock on a sweltering late summer afternoon Emmanuel Akindele sat behind the counter of the Zanzibar feeding Jackson the marmoset his first fierce cocktail of the day.

A thin, nervy thirty-year-old, Emmanuel had been rescued off Lampedusa the previous spring. Two thousand dollars that cost him to the Libyan people smugglers, pretty much all his family back home in a Lagos slum possessed. He’d thought himself dead already by the time the Red Cross boat came along and pulled him from a sea so cold it seemed to freeze his bones.

Now, in a kind of life, he spent hour upon hour with this sad and savage little animal, a miserable bundle of bone and fur, barely the size of a cat. Something trapped and helpless, and probably beyond hope. The creature kept thrusting a skinny arm through the bars of its rusty metal cage, holding out a grubby shot glass. A simian alcoholic and Emmanuel couldn’t think of anything else but to dull its senses in place of his own.

He’d inherited Jackson when the gang boss put him into the Zanzibar nine months earlier, after he’d earned what the mob men called promotion from pushing cheap counterfeit bags to the tourists on the beach at Locri. The creature was part of the furniture in the cramped, windowless bar, like the broken Playboy pin table, the cheap paintings of Marilyn Monroe, the satellite TV system with an illegal card to pick up premium sports channels from around the world.

He’d thought about letting the monkey go. About driving out of the grey and sprawling city to one of the bare back roads that led to the desolate hills rising from the coast. There the sparse tracts of scrappy brown vegetation reminded him of the countryside back home. He could see himself taking the cage out of the boot and watching the scrawny broken animal limp off into the dry, barren lower reaches of Aspromonte, the sprawling mountain that rose behind Italy’s extended toe like the humped back of a slumbering giant.

Jackson would be a corpse in a few hours, a day at most. Nothing foreign lived long in that bleak wasteland. Some things were dead before they even got there. The gang men who employed him, members of the Calabrian mafia, the ’Ndrangheta, saw the place, with its wildernesses full of snakes and spiders and, some said, wolves too, as their natural home. The worst thing that could happen to a man was to be told he was going for a ‘walk in the hills’. You never came back. This was where the mobsters took their victims, where they hid the men and women they kidnapped for money, slicing off a finger or an ear when they needed to raise the temperature a little. Even life in a cage, begging for drinks, getting laughed at by the scum who made up the Zanzibar’s clientele, was better than abandonment in that brutal, inhospitable expanse of desolate rock and thorns.

The bar was empty, as it usually was at this time of the afternoon. Customers didn’t begin to turn up until five or so and they didn’t stay long once their business was done. He had beer and wine and unbranded bottles of spirits that could, at a push, be turned into cheap cocktails. There were even a few panini and packets of cheese and cold meat from the supermarket should a rare soul feel hungry. Not that any of this was of great importance. The Zanzibar was a covert market place and he was its tame host, there to serve and nothing more, certainly not to listen because that could prove very dangerous indeed.

This lost little dive, an airless converted storeroom in the back streets of sprawling Reggio, served as an illicit stock exchange where millions of dollars might be exchanged over a couple of glasses of warm Negroni and a shake of the hand. Five minutes away on foot down a narrow industrial road lay the port, a place where boats large and small, legal and nefarious, came and went through the Strait of Messina, past Sicily, out of Europe altogether. Some sailed east, to Turkey, the Balkans and beyond, bringing back narcotics and human traffic, women and cheap labour for the black market. Some went south, to Africa, another continent, his own, which was, Emmanuel often reminded himself, nearer to Reggio than Rome. As far as he could see those vessels returned with much the same kind of goods too, just ones that sometimes bore a different colour and a price tag that was yet more cruel.

On occasion the merchandise found its way into the Zanzibar. He wasn’t happy with that idea. The dope, hidden in the storeroom, could put him in prison for years, even though he didn’t stand to take a cent of profit from its sale. The men and women he had to hide sometimes … He’d got used to the look in their faces, the mixture of fear and self-loathing. They, like him, had started on the journey to Europe out of naive hope and desperation, seeking only what any human being ought to regard as his or her right: some way to earn a decent living with a little dignity.

That fantasy ended in the back streets of Reggio when the scales surely fell from their eyes. Watching the bright, sharp spark of fear in the faces of the women was the worst. They never used females to sell fake bags to tourists or run bags of dope out to the chains of pedlars. There was only one reason for them to be here.

He hated the Zanzibar and the tiny, dingy room above it, one entirely without windows, where he was forced to live. When he got back home, not rich but no longer dirt poor, he’d sho

ut the truth out loud. The men who tempted you out of your home, who dangled riches and luxury in front of your eyes as you stood there, stupid, transfixed, on the doorstep of your miserable little shack, these lying bastards were nothing more than the missionaries and hard-faced, white company men of old, waving trinkets with one hand, hiding the vicious tools of enslavement, a gun and a Bible, tight behind their backs with the other.

Europe was no place for men like him.

That message was one he would deliver soon. Emmanuel was both terrified and proud that, over the previous few months, he’d managed to skim some money from the meagre cash passing over the counter of the Zanzibar. Soon he would have enough stashed away to buy a one-way economy ticket back to Lagos. The route would be the long way round, from Catania in Sicily to Bucharest then Addis Ababa, and finally home. He didn’t dare countenance the direct flight, through Rome. The men from Aspromonte would be mad as hell because stealing from them was the worst thing a man could do, an automatic death sentence, carried out without a second thought. They had people everywhere in Italy, maybe beyond, not that he liked to think about that possibility. Emmanuel had worked hard to convince himself that once he was on his plane out of Sicily, headed briefly for Romania, he’d be free of them for good, and that was what he wanted most of all.

The marmoset broke the daydream by rattling his shot glass hard across the bars of its cage.

‘Stupid little animal,’ Emmanuel spat at it. He snatched away the glass and threw in some fresh peanuts instead. The animal screeched furiously and flew at the bars, yellow teeth bared, its tiny, insane eyes glowering at him. ‘Eat something. Eat now or I shall take you out to Aspromonte myself. You go play with the wolves there. See who wins.’

It kept on screeching and screeching. The two of them had been here before. The creature would never give up. It had no reason.

The Garden of Angels

The Garden of Angels Solstice

Solstice Death in Seville

Death in Seville A Season for the Dead

A Season for the Dead The Killing tk-1

The Killing tk-1 The Savage Shore

The Savage Shore Dante's Numbers

Dante's Numbers Sacred Cut

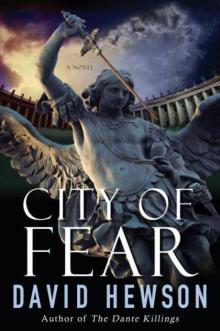

Sacred Cut City of Fear nc-8

City of Fear nc-8 The Blue Demon

The Blue Demon The Garden of Evil

The Garden of Evil The Lizard's Bite

The Lizard's Bite The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Sleep Baby Sleep

Sleep Baby Sleep Lucifer's Shadow

Lucifer's Shadow Season for the Dead

Season for the Dead The Seventh Sacrament

The Seventh Sacrament The Garden of Evil nc-6

The Garden of Evil nc-6 Juliet & Romeo

Juliet & Romeo A Season for the Dead nc-1

A Season for the Dead nc-1 The Fallen Angel nc-9

The Fallen Angel nc-9 Little Sister

Little Sister The Lizard's Bite nc-4

The Lizard's Bite nc-4 The Killing 2

The Killing 2 The Fallen Angel

The Fallen Angel The Sacred Cut

The Sacred Cut Carnival for the Dead

Carnival for the Dead The Villa of Mysteries nc-2

The Villa of Mysteries nc-2 Macbeth

Macbeth The Killing - 01 - The Killing

The Killing - 01 - The Killing The Villa of Mysteries

The Villa of Mysteries Dante's Numbers nc-7

Dante's Numbers nc-7 The Sacred Cut nc-3

The Sacred Cut nc-3 The Seventh Sacrament nc-5

The Seventh Sacrament nc-5