- Home

- David Hewson

Carnival for the Dead Page 4

Carnival for the Dead Read online

Page 4

She laughed self-consciously, a warm and pleasant sound, clearly expecting to see someone else.

‘I’m so sorry,’ she said, in an accent that had a foreign tone to it, ‘I heard noises. I thought it must be Sofia.’

Teresa explained herself and told what little she knew. She waited. The young woman, who could have been no more than twenty she imagined, listened and shook her head.

‘This is very strange,’ she said. ‘I haven’t seen her in a week. She never said she was going away. Nothing. To you?’

‘Only that she had some kind of problem.’

‘What kind?’

‘I don’t know,’ Teresa confessed.

‘Camilla Dushku.’ The young woman held out a white-gloved hand. ‘I live in the apartment downstairs. We should talk in the morning. I’m sorry. I have to go to work now.’ A sigh. ‘Handing out overpriced champagne to the multiple mistresses of Russian businessmen. Welcome to Carnevale. Here. Now at least something makes sense.’

She held out the flowers and the envelope.

‘They’re addressed to you, not Sofia. Both of them. In this apartment,’ Camilla explained. ‘The post came yesterday. The flowers this evening. No one answered the bell so I signed for them. I thought Sofia must have missed the envelope when she came in.’

‘No one knew I was here,’ Teresa told her.

The young woman grinned apologetically.

‘Someone did. Look. Your name. This apartment.’

Teresa Lupo took them then watched her go. She checked the tag on the bouquet and the address. Camilla Dushku was right. Then she realized there was a logical explanation for the flowers at least. She’d left a voicemail message for Peroni through the Questura in Rome, with the address in Venice and a note about her visit. She’d mentioned an unspecified problem with Sofia too, no more than that since she didn’t want to worry him. It was typical of the man that he would find time on assignment in Sicily to remember her. Typical too, she thought, checking the rest of the card, that he forgot to add his name or the simplest of messages.

She went back into the apartment, tearing open the manila envelope. Inside was nothing but a sheaf of loose sheets, perhaps thirty pages of text in an old-fashioned typewriter font, double-spaced, like a book manuscript, but printed on a curious thick paper the colour of mustard.

One thing at a time.

Questura rules said she wasn’t supposed to contact Peroni. That didn’t mean she couldn’t send a quick text saying she was fine and thanking him for the generous bouquet. It went off in an instant and she wondered what he was doing at that moment, with Nic Costa and Falcone, in Palermo perhaps or one of the mob towns in the interior.

There was no point in speculation. He wouldn’t even turn on his private phone until he was off duty, back in the hotel or whatever police house the Sicilian authorities had found for them.

She took the manuscript with her into the bedroom, got undressed and lay beneath the sheets, reading by the weak light of the lamp set in the headboard. The work appeared to be a short story with the title Carpaccio’s Dog. The typeface was deceptive. It was clearly the product of a modern laser or inkjet printer though the strangely heavy paper stock continued to puzzle her.

She flicked through the sheets. This seemed a professional document, with the title on the top of each and a running page and word count. Yet nowhere was there any name for the author.

One page, she thought. Perhaps two.

Fifteen minutes later she realized it was impossible to stop, even when there was a distant beep from her phone in the living room.

So Teresa Lupo failed to see that Peroni had texted back from distant Sicily with a brief message.

What flowers?

Carpaccio’s Dog

Jerome Aitchison, a tall and solitary Englishman of fifty-three years, stood in the narrow Castello street transfixed by the creature before him. The dog was small, less than a foot high, with a clean spiky coat the colour of bleached bone. It possessed keen black eyes and sharp, triangular ears pricked and alert over a compact head little larger than a grapefruit. The animal’s damp and shiny nose was held high pointing, like its gaze, directly at Aitchison. No more than a single stride separated them in the narrow, dark alley where they had encountered one another.

The dog had been waiting for him. He felt sure of it.

There was a sense of immediate recognition, on both sides a part of him seemed to say. One hour before he had met this same small bundle of fur, determinedly rigid in a posture identical to the one it held now: taut on its haunches, which were very much like those of a chicken, back feet aligned geometrically behind its front paws, as if posing for a photograph.

The attentive, engaged expression on its tiny foxlike face was unchanged and, just as then, he found himself struggling, through inexperience, bafflement, and a muggy, befuddling cloud of recent alcohol, to make sense of its meaning. Expectation of a ball or toy thrown in play? A word of praise? Some gesture of encouragement?

There had never been a dog in his life, not as an introspective only child nor later when he moved into college rooms and fell, easily he had to admit, into the lonely though consuming round of a bachelor existence. He had no idea how to address the thing, let alone amuse it. There was, moreover, a more subtle problem. When he last saw the diminutive beast it was not in the least sense alive. The creature existed as paint on a canvas that was, if he recalled correctly, more than five hundred years old. A small and perhaps insignificant detail of a compelling and impenetrable work he’d stumbled upon after a long and rather over-indulgent lunch in a tourist-trap restaurant along the Via Garibaldi in Castello.

Staring at the minuscule creature in front of him, which seemed too independent to be anyone’s pet, he wished someone would join them in the cramped, dank alley, puncturing this strange, dreamlike interlude, bringing him down to earth. It was just after seven o’clock on a chill January evening and Venice, this part at least, seemed quite deserted. There was not the slightest noise from any of the grimy, ramshackle terraced homes around him, not a light behind the windows. It was as if nothing existed in the city save the two of them: a middle-aged academic distracted from an endless, circular rumination on the destruction of his career and a tiny, seemingly lively animal, intent on monopolizing his attention and posing a question he could not possibly begin to understand.

He bent forward and, with an unsteady hand, cut through the air in front of him, uttering the one appropriate word that came into his head.

‘Shoo!’ Aitchison declared, sweeping away the inky night with his arm.

The dog continued to sit directly in the centre of the squalid lane, blocking his way.

‘Shoo, damn you,’ he repeated.

The tiny white head gazed up at him in the light of a waxing moon just visible through a herringbone sky that spoke of snow. The animal remained as motionless as it had been on the wall of the place, very like a church, where he had first seen it.

He checked himself. Drink had been taken. Even so it seemed ridiculous to be talking to what was either a phantasm from a brief waking dream or a neighbourhood stray which, through nothing more than centuries of breeding, bore an extraordinary resemblance to a long-dead Castello mongrel.

Aitchison ran the sleeve of his coat across his face, rubbing musty bachelor gabardine against whiskery bachelor cheeks. What was that look on the tiny animal’s face? It appeared identical to when he first witnessed it on canvas. Longing? An eager adulation? Or was there even, and this last thought would once have amused him, some impudent hint of condescension in the creature’s bright, black eyes?

Condescension . . . God knew he’d seen enough of that of late.

‘Shoo, you bloody little beast . . .’

The dog stayed as rigid and motionless as one of the stone lions by the Arsenale gates which he had passed not long before.

‘Get lost! Bugger off!’

It occurred to him that this was stupid in the extreme. The

animal, if it knew any language at all, would be familiar with Italian. Or the local Veneto, even. Not angry vernacular English.

The red rage of ire, stoked by cheap alcohol, self-disgust and recent resentment, filled his head. A stream of vile invective rose in the night. Aitchison stepped forward and aimed a tipsy kick at the creature on the cobblestones, missed, slipped on a puddle that was minded to turn to ice, lost his footing and fell backwards, landing hard on his backside, squawking with pain.

There was the briefest of yelps from somewhere ahead of him, a high-pitched sound that seemed to contain an audible note of triumph. After a few brief seconds of mournful contemplation he looked around and was relieved to see he was once again alone. The way ahead – the direction, roughly, in which he had come from his inexpensive lodgings – appeared clear as he’d hoped, though the narrow alley of black cobblestones was now gleaming with the incipient arrival of what could only be frost, icy white beneath the dim light of a small and inadequate street lamp.

Aitchison got up, cleaned the dirt and moss from his clothes as best he could, then stumbled forward, peering round the next corner, fearful that he might see the same white shape sitting boldly out in the middle of the path, waiting. There was nothing. Carefully he felt his arms and legs. No broken bones. A bruise perhaps. A graze. He was shivering though and he wondered if this was only because of the sudden bitter cold that had closed in not long before he saw the damned dog.

Reassured to be alone once more he crossed the low stone bridge that soon rose to meet him and walked very briskly in the direction he felt sure would, at some stage, fetch up close to the broad piazza of Giovanni e Paolo – which the locals, he noted, invariably called Zanipolo for some reason – and home.

It took only three wrong turnings, two of them ending in the dead black water of a narrow canal, before he found his bearings. This was an improvement on any of the previous six nights in the city. Then he rounded a half-familiar corner and saw the crooked iron railing along the canalside path that led towards his lodgings.

The tiny café on the corner was about to close in spite of the early hour. It was damnably hard to stay drunk in this city.

He strode in with a determination that told the owner he would be served, whatever.

The thickset Venetian behind the counter recognized him. His expression was as impenetrable as that of the dog in the night.

‘I saw . . .’ the Englishman began, then stopped as he watched the man reach for the grappa bottle without even asking. Aitchison didn’t wish to appear foolish. Besides, this was his last opportunity for a drink. If he were thrown out . . .

‘Saw what, signore?’ the barman asked in good English.

‘Nothing.’

The man poured a generous glass then glanced at his watch.

‘Just a dog . . .’ Aitchison murmured before taking a sip of something that tasted distinctly chemical, as if it bore a faint relationship to petroleum.

‘That is all you see in Venice?’ the barman asked. ‘A dog?’

Aitchison slunk to a table in the corner. By eight thirty, after much vacillation, and a failed attempt to extract one more drink, he was out in the street again staring at the sky. The feathers of cloud now had the texture of swans’ wings. They made him think of the Cam in summer, lazy days of beer and books, with the odd sly eye cast towards the pretty girls giggling in the procession of punts zigzagging up and down the still green water.

Another lifetime. One to which he would never return.

Nights were never easy since the unpleasantness and the allegations – shocking, untrue, though not entirely without some flimsy basis – made by the young girl student towards whom he had once felt great warmth and admiration.

When he decided to flee Cambridge in the dead week between Christmas and New Year, Aitchison had searched the college computer system seeking ideas. There he’d found the lodgings in Castello, recommended on a noticeboard by a student who had used them while backpacking around Italy. Aitchison hadn’t dared contact the person responsible to inquire about their suitability. He was a pariah already by that time. The rumours were beginning to fly, in dining rooms, in pubs, whispered, he imagined, at college parties during the darkening days of December as his downfall seemed to gain more salacious detail with every passing day. St Jerome – he knew the nickname they gave him, and that it dated back decades – had fallen from on high. All his achievements, his years of work, counted for nothing. A pious man had been revealed as a hypocrite, or so they thought. It was the kind of small, personal tragedy that the enclosed world of a Cambridge college adored.

There was no time to plan, which was, in itself, deeply disturbing. He was a senior lecturer in actuarial science, a solid faculty member with a well-proven record, respected in every way. Perhaps a little too individual, too different to gain what he had once dreamed of, a professorship. Nevertheless he had won some esteem through a combination of talent, hard work and routine. Planning seemed, to Jerome Aitchison, an intrinsic and necessary part of daily life, like breathing or going to the toilet. That was why he chose actuarial science as his field of study. He was a good teacher too and had watched many of his students go on to make great fortunes in the City of London through the subtle arithmetical skills he had taught them, all with one aim: to predict the span of life itself.

Over the previous three decades he had given so many lectures on the subject he felt it was a part of him, an invisible limb. The talks he enjoyed most were for lay audiences, Women’s Institutes and library groups, people he could amuse with history and obscure facts. Had they any idea the first actuarial calculation – an attempt to link compound interest with various mortality rates – was performed by none other than the seventeenth-century Prime Minister of the Netherlands, Johan de Witt? That de Witt’s The Worth of Life Annuities Compared to Redemption Bonds represented the first real effort to analyse probability and chance, to pull hard fact from the superstitious ether of fancy, substituting blind faith with science?

Of course they hadn’t. Everyone died, but no one wanted to contemplate their own end. Nor had the Dutchman’s insights done the unfortunate man any personal good. While de Witt had begun to formulate actuarial skills that would one day enrich the insurance and pensions industries, keen to place the very best-informed bets on the life spans of those whose policies they held, the Netherlands remained steadfastly unimpressed. During a small and uninteresting war the mob rose up and entrapped the hapless politician and his brother in The Hague, promptly disembowelling and decapitating them, carving out their hearts and hanging their broken bodies from a scaffold.

Two years before Aitchison had visited Amsterdam for an international conference on the future of actuary. There he had found himself wandering into the Rijksmuseum. Almost immediately he had been confronted by a haunting and exceedingly gory canvas depicting the miserable, bloody demise of the de Witt brothers, hung upside down from the gibbet, corpses slashed and torn. He had, up to this point, regarded the Dutch as the mildest of men.

On hearing his recounting of this story Ursula Downing, the young woman whose bright, intelligent, smiling face had brought Jerome Aitchison to his present predicament, jokingly asked why such a clever man as Johan de Witt could not concoct a mathematical formula that predicted the end of his own life.

‘Don’t forget chance,’ Aitchison had told her earnestly. ‘Never mistake probability for certainty.’

‘Or mess with politics,’ she’d added, staring at him wide-eyed, as beautiful as Raphael’s La Fornarina.

Ursula was angling for a first and would get it. Aitchison had no doubt about that. The dreadful, calamitous letter she had left behind when Michaelmas term ended would hinder her progress not one whit. Accusations of sexual impropriety and vague threats of legal action sent a chill through the flimsy spines of college administrators, none of whom weighed Aitchison’s two and a half decades of loyal service against the unproven and unprovable accusations of a child. No arithmetical co

nceit could have predicted his downfall, nor the empty aching chasm in his heart that her absence caused: one aggravated by her treachery, not attenuated as a mathematician might have expected.

As he lay on the hard, cold single bed in the first-floor room of the simple hostel in a back street of Castello, the sole guest as far as he could gather, he found his fuddled head filling with thoughts and memories, images and half-formed fantasies. Questions too.

Why did he wander into art galleries so easily? Was it simply because those dead faces on the wall never objected to his avid and curious stares the way the living did? He’d had no need to visit the Rijksmuseum and find himself confronted by the ghastly end of a man who, in the confined reality of ink on paper, trapped within the words and pages of a book, was nothing less than a hero to actuaries around the world. Nor had he consciously decided to enter the building that contained the painting with the curious dog, thus bringing about the strange waking dream – it could be nothing else, surely? – that had afflicted him on the way home.

‘You’re a fool, Jerome,’ he murmured to himself.

His return ticket on the budget airline could not be taken for another four days. It was important to conserve money. He’d little expectation that he could resume his position. There were even furtive whispers that his pension might be affected which, for reasons none in the bursar’s office appeared to appreciate, he found utterly unimaginable, a horror tantamount to the bloody end wrought by the Dutch mob on de Witt himself.

For the next few days there was nothing else to do but wander the desolate streets of Venice.

‘A fool . . .’ he whispered, and closed his eyes, willing himself to sleep.

There were noises outside the single small, dingy window that gave onto the cobbled street. Voices from time to time, of drinkers and diners making their happy way home from some establishment that served the Venetians till the early hours, keeping out the foreigners, condemning them to cold damp bedrooms.

The Garden of Angels

The Garden of Angels Solstice

Solstice Death in Seville

Death in Seville A Season for the Dead

A Season for the Dead The Killing tk-1

The Killing tk-1 The Savage Shore

The Savage Shore Dante's Numbers

Dante's Numbers Sacred Cut

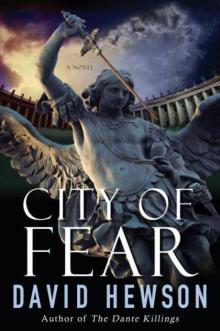

Sacred Cut City of Fear nc-8

City of Fear nc-8 The Blue Demon

The Blue Demon The Garden of Evil

The Garden of Evil The Lizard's Bite

The Lizard's Bite The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Sleep Baby Sleep

Sleep Baby Sleep Lucifer's Shadow

Lucifer's Shadow Season for the Dead

Season for the Dead The Seventh Sacrament

The Seventh Sacrament The Garden of Evil nc-6

The Garden of Evil nc-6 Juliet & Romeo

Juliet & Romeo A Season for the Dead nc-1

A Season for the Dead nc-1 The Fallen Angel nc-9

The Fallen Angel nc-9 Little Sister

Little Sister The Lizard's Bite nc-4

The Lizard's Bite nc-4 The Killing 2

The Killing 2 The Fallen Angel

The Fallen Angel The Sacred Cut

The Sacred Cut Carnival for the Dead

Carnival for the Dead The Villa of Mysteries nc-2

The Villa of Mysteries nc-2 Macbeth

Macbeth The Killing - 01 - The Killing

The Killing - 01 - The Killing The Villa of Mysteries

The Villa of Mysteries Dante's Numbers nc-7

Dante's Numbers nc-7 The Sacred Cut nc-3

The Sacred Cut nc-3 The Seventh Sacrament nc-5

The Seventh Sacrament nc-5