- Home

- David Hewson

The Villa of Mysteries Page 22

The Villa of Mysteries Read online

Page 22

For a fleeting moment he wished he’d never left that beach in Sri Lanka, never caught the plane home to these complexities. He’d felt old recently. The renewed, chaste presence of Rachele D’Amato did his mental state no good at all. The pressure was something he could take. It was the doubts that bothered him. He wanted certainties in his life, not shadows and ghosts.

“Where the hell is everyone?” he scowled, and felt, for the first time in many a month, the edges of his temper beginning to fray.

The moment Teresa Lupo left Regina Morrison’s office Monkboy was on the line, screaming for all he was worth, making it dead plain that Falcone was possibly in the foulest mood in history and wanted her on the scene now. She drove through the choked streets, thinking about what she had heard, not wondering for a moment how she would explain her absence or the fact that, for the second time in two days, she’d wilfully trodden on cop territory.

Dead people didn’t run away. There was nothing she could do for this new corpse that Silvio Di Capua couldn’t. All the hard work came later. Falcone would surely realize that. Most of all, she had a result. She didn’t expect him to be grateful. She didn’t expect to get bawled out either. While the rest of them were stumbling around in the dark, grasping at cobwebs, she’d found something concrete: the photograph of Barbara Martelli and Eleanor Jamieson in the private files of Professor Randolph Kirk, a man the lovely Barbara had despatched so efficiently the day before.

“Shithead,” she mouthed, with precious little enthusiasm, at a white van blocking the street. Some Chinese guy was unloading boxes out of the back and, very slowly, running them into a little gift shop. She looked into the window. It was full of the crap cheap Chinese gift shops sold: bright pink pyjamas, plastic back-scratchers, calendars with dragons on them. It all seemed so irrelevant.

She opened the window and yelled, “Hey. Move it.”

The man put down the box he was carrying, turned and said something which sounded very like “Fluck you.”

Red mist swirled in front of her eyes. She pulled out her ID card, hoping the state police seal would do the trick, waved it in his direction and screeched, “No, asshole, fluck you.”

He hissed something underneath his breath that made her glad she didn’t understand Cantonese, then slowly climbed into the van and started to clunk it through the gears.

The riddle still hung in front of her, grey, shapeless. Was her own presence at the site merely a rotten coincidence? Did Barbara decide to off the professor anyway—maybe through some recurring bad dreams—then add the one and only witness to the list? Had Kirk called her to say someone was around asking awkward questions, in such a panic that she decided to shut him up for good? Was that what a Maenad did? Dispose of the god if he lost his sparkle? Or did Kirk phone someone else, someone who knew Barbara Martelli, understood she’d become a Maenad somewhere along the way and just given her the job: out you go, girl, it’s whacking time, and don’t forget to clear up any prying pathologists who happen to walk into the firing line.

They’d never know. The first thing the cops had checked was the phone records. She’d asked that morning. They hadn’t a clue whom Kirk had called. There was no redial button on Kirk’s ancient handset. The phone company didn’t log local calls.

She was starting to think like a cop now and it scared her. All these possibilities lay in the dark, limitless recesses of the imagination, a place she was trained to avoid. A place that, if she were honest with herself, had begun to scare her. That was why she started blubbing in front of a complete stranger, why it took her a good fifteen minutes to recover sufficient composure to get on with the day. That and the shitty virus fighting it out with two quick shots of Glenmorangie in her bloodstream. Life would be so much easier if the dead could come back and talk, just for a little while. She’d drive over to the morgue, stare at the mummified cadaver that had once been Eleanor Jamieson, and murmur, Tell Teresa all about it, sweetie. Get it off your mahogany chest.

Still, that corpse had spoken to someone. It had said: not everything dies. And Suzi Julius, with her fateful blonde looks, had sparked something too. Cause and effect didn’t respect mortality.

The white van lumbered off the pavement and rolled down towards the low shape of the Colosseum at the end of the street. Teresa Lupo’s new yellow Fiat, provided by the insurance company and already sporting a couple of fresh dents, sat stationary in the road. The horns behind her began to yell.

She wound down the window and yelled back at the creep in the Alfa on her tail. “Can’t you see I am thinking, you crapulent piece of pus?”

Then she put the car gently into gear and drove down the Via dei Serpenti at a measured, steady pace, trying to put her thoughts in order.

When she walked into Beniamino Vercillo’s cellar she felt like putting her hands over her ears, like running away from everything and finding some oblivion in a long, cold drink. She’d seen this so many times before, the path team hanging round the corpse, waiting to be told what to do, the scene-of-crime men in their white bunny suits combing the place for shards of information. And Falcone, this time with the woman from the DIA, standing at the back, watching everything like a hawk, throwing questions at Nic Costa and Peroni, unhappy, uncommunicative.

The tall inspector broke off from barking at his men. “And where’ve you been? In case you haven’t noticed there’s work to be done.”

She held up both hands in deference. “Sorry,” she answered meekly. “Don’t feel the need to ask how I am. I get people trying to kill me most days.”

Falcone demurred slightly. “We need you.”

“I’ll take that as an apology though a simple sorry would have sufficed. How’s it going with the missing girl by the way?”

“What?”

“The girl?”

Falcone scowled at her. “Leave the live ones to us.”

She looked at the body behind the desk. There’d been so many over the years, it was like being on a factory line. Now something was different. When Teresa Lupo looked at this corpse, the professional, unconscious side of her already assessing what she saw, a low, rebel voice started sounding in her head, getting louder and louder and louder, until it drowned out everything else, the blood, the questions, the tension and the fears.

“I can’t do this anymore,” she murmured, and wondered who was speaking: her or the rebel voice. And whether they were, perhaps, one and the same.

Monkboy hovered over the body, watching her, waiting for a lead.

The voice got louder. It was her voice.

“Is anybody listening here?” she yelled, and even the forensic people dusting down the office furniture became still.

“I can’t do this anymore,” Teresa Lupo said again, more quietly. “He’s dead. That’s all there is to say. There’s a girl out there still breathing and here we are, like undertakers or something, staring at a corpse.”

She felt a hand on her arm. It was Costa.

“Don’t try that one,” she murmured. Her hands were shaking. Her head felt as if it might explode. She could hardly open the bag, hardly get her hands around the file Regina Morrison had given her, find the strength to take out the pictures. “I trained as a doctor. I learned how to distinguish the symptoms from the disease. This is irrelevant. This is a symptom, nothing else. This—”

She scattered several of the photos on the table, over the sheets of numbers, obliterating them. She made sure the most important one, Barbara and Eleanor before, was on the top.

“—This is the disease.”

Falcone, Costa, Peroni and Rachele D’Amato had to push their way through the men in bunny suits to get a good look. Someone swore softly in amazement. The girls looked even more beautiful now, Teresa thought. And it was so easy to imagine Suzi Julius just walking into the frame, shaking hands with them, not knowing they were both dead, sixteen years apart, but dead is dead, dead is a place where the years don’t matter.

“Where did you get these?” Falcone ask

ed, furious.

“Randolph Kirk’s office. This morning.”

“What?” he roared.

“Don’t rupture something,” she said quietly. “You didn’t look there. You weren’t even interested.”

“I didn’t have the damn time!”

His long brown nose was sniffing at her. She thought of the drinks Regina Morrison had given her. The bastard never missed a thing.

“Jesus Christ, woman,” he snapped. “You’ve been drinking. This is the end. Because of you—”

He didn’t finish the sentence. He was too livid.

“Because of me what?” she yelled back. “What? Your beautiful traffic cop is dead? Is that what you think?” She stared at the men in the room. “Is that what you all think? May I remind you of one fact? Your beautiful traffic cop was a cold-blooded murderer. Maybe she did it for herself. Maybe she did it because someone told her to. But she killed someone. She’d have killed me too if I’d let her. I didn’t cause any of this. It was just there waiting to happen, and if it had been somebody else maybe there’d be two victims, more even, lying in the morgue right now, not one. Hell, maybe there are, maybe there have been more over the years. And we wouldn’t know. Because Barbara Martelli would still be riding that bike of hers, smiling sweetly all the time to fire up all your wet dreams, because none of you, not one, could possibly believe what she really was. Thanks to me you found out. Sorry—” She said this last very slowly, just to make sure the point went in. “I apologize. That’s the trouble with the truth. Sometimes it hurts.”

“You have damaged this investigation,” Falcone said wearily. “You have overstepped your position.”

“There’s a missing girl out there!”

“We know there’s a missing girl out there,” Falcone replied, and threw the four photos Peroni had given him onto the table to join the others. “We know she’s been abducted. We know, too, that somehow these things are all linked. This is a murder inquiry and an abduction inquiry and I will allot what precious resources I have in my power to try and ensure no one else gets killed.”

“Oh,” she said softly, staring at the pictures. “I’m sorry.” She was shaking her head. She looked utterly lost. “I don’t know what’s wrong with me. I’ve got the flu, I think. What a pathetic excuse.”

Costa took her arm again and this time she didn’t resist. “Go home,” he said. “You shouldn’t be working anyway. Not after what happened yesterday.”

“What happened yesterday is why I’m working. Don’t you understand?”

“Teresa,” Silvio Di Capua bleated. “We need you.”

“You heard the man,” she whispered, knowing the tears were standing in her eyes again, starting to roll, starting to be obvious to them all, like a sign saying, Look at Crazy Teresa, she really is crazy now. “I’m sorry, Silvio. I can’t do this . . . shit anymore.”

The place stank of blood and the sweat of men. She walked to the door, wanting to be outside, wanting to feel fresh air in her lungs, knowing it wasn’t there anyway, that all she’d inhale was the traffic smog of Rome, waiting to poison her from the inside out.

And she was thinking all the time: what was it the crazy god offered Barbara Martelli and Eleanor Jamieson really? Freedom from all this crap? A small dark private place where you were what you were and no one else looked, no one else judged, where duty and routine and the dead, dull round of daily life were all a million miles away because in this new place, just for a moment, you could persuade yourself you had a part of some god inside you too? Could that have been the gift? And if it was, could anyone in the world have turned it down?

Emilio Neri refused to skulk around like a criminal, hiding from everything, a fugitive for no good reason at all. But even without an unwelcome visit from the cops and the DIA he could read the signs, digest the intelligence coming in through the channels he’d created over the years. He had to face decisions, make choices, and for the first time in his life he found that difficult. This was a new, unprecedented situation. Until he made up his mind how to proceed he felt he had little choice but to hole up in the house, trying not to let Adele and Mickey’s endless bickering get on his nerves. It was time to stop pretending he could lead from the front, as he had twenty years before, when he moved from capo to boss. Now he had to act his age, directing his troops, being the general, keeping their trust. He was getting too old for the tough stuff. He needed others to do the work.

There were risks too. He wondered what they thought in the ranks. When he was with the men, he had them tight in his hand. Now he was in danger of seeming aloof, his grip less sure. Adele and Mickey didn’t help either. A man who couldn’t control his own family could hardly demand respect from the ranks. He’d asked Bruno Bucci to keep an ear open to listen for any whispered remarks that might be the first indication of revolt. These were hazardous times, and not just from the obvious direction. Whatever he said in private, he had to make sure the Sicilians remained happy. He had to convince the foot soldiers it was in their interests to keep their hats in the ring with him too. Money only went so far. He needed to cement their respect, to continue to be their boss.

Then Bucci came in with more news about Beniamino Vercillo. The cops were trying to keep things quiet, but Neri’s mob had good sources. They mentioned the oddest part of the case: that the killer had been wearing some kind of ancient theatrical costume. This was, it seemed to Neri, a message, surely. The situation was more serious than he had foreseen. For a while, he was dumbstruck, floundering in his own doubts with no one to turn to. He blamed himself. As soon as he’d known a war could be on the way—as soon as those reports of American hoods coming in through Fiumicino reached him—he should have acted. If conflict was inevitable, the advantage always lay with the party that struck first. The Americans understood that lesson instinctively. Instead, he’d hesitated, and now they’d punished him in the most brutal and unexpected of ways.

Vercillo was a civilian. If they’d wanted to make a hit in order to prove a point, there were plenty of accepted targets they could nail: neighbourhood capi, underlings, street men, pimps. Instead they picked a skinny little accountant. It made no sense. It was offensive. Neri had no time for Vercillo personally. He wasn’t even a real employee. It had never occurred to Neri to warn the man to stay at home for a while, to keep his head down until the air cleared. However bitter a war got, it just didn’t involve people that far down the ladder. This was an unwritten rule, a line you never crossed.

Like killing someone’s relative, a wife or a daughter, Neri thought.

Bucci watched him, impassive, stolid, waiting for instructions.

“Boss?” he said finally.

“Give me a chance,” Neri replied with a scowl. “You got to think your way through these things.”

The big tough hood from Turin was silent after that. Neri was glad of his presence. He needed a man of substance in his trust.

“How are the boys feeling?” Neri asked.

“About anything in particular?”

“The mood. Morale.”

Bucci squirmed a little. Neri recognized the signs. They weren’t good. “They get bored easy, boss. Men do in situations like this. They get hyped up like something’s going to happen. When it doesn’t they get to feel awkward. Like they’re wasting their time.”

“I’m paying them well to waste their time,” Neri grunted.

“Yeah. But you know their kind. It’s about more than money. Besides, one of them’s cousin to that poor bastard Vercillo. He’s got a score to settle.”

“So you’re saying what, Bruno?”

Bucci considered his answer carefully. “I’m saying that maybe it’s not a good idea to sit here waiting for the next thing to happen to us. They’re good guys but I don’t want to push them too far.”

Neri’s cold gaze didn’t leave Bucci for a second. “Are they loyal?”

“Sure. As loyal as anyone gets these days. But you got to recognize their self-interest. You got

to massage their egos too. These are made men. They don’t like thinking they’re just doing security work or something. It’d help me no end if we saw a little action. Let these assholes know where they stand.”

“I was thinking the same thing,” Neri lied. Something else was bugging him. How had they known about Vercillo? He was a back-room guy. From the outside he looked straight. How did Wallis find him? Maybe Vercillo was less discreet than Neri expected. Maybe he’d been selling information on the side, and found out how dangerous that game can be. “You got any information about who’s doing this? Names? Addresses?”

“Not yet. The street’s not talking much out there at the moment. Hell, if it’s some people the American brought in for the job, our people probably don’t know them anyway. If you want my honest opinion—” Bucci dried up.

“Well?”

“We’re not going to get any more information than we have right now. People are bound to be sitting back on the sidelines, watching. They want to see who comes out on top. No one’s going to want to do you any favours, not unless they’re in with us deep already. It doesn’t make sense.”

Neri said nothing.

“You don’t mind me being frank,” Bucci said carefully.

“No,” Neri moaned, “it’s what I need. Jesus, these are people who’ve been sucking my blood for years!”

“Look, boss. You got plenty of respect with the guys here. Provided they don’t get pushed too far. Outside—” He didn’t say any more. He didn’t have to.

“Respect,” Neri grumbled, his face like thunder. “Tell the truth. Do they think I’m too old or what?”

The Garden of Angels

The Garden of Angels Solstice

Solstice Death in Seville

Death in Seville A Season for the Dead

A Season for the Dead The Killing tk-1

The Killing tk-1 The Savage Shore

The Savage Shore Dante's Numbers

Dante's Numbers Sacred Cut

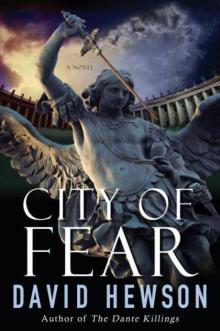

Sacred Cut City of Fear nc-8

City of Fear nc-8 The Blue Demon

The Blue Demon The Garden of Evil

The Garden of Evil The Lizard's Bite

The Lizard's Bite The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Sleep Baby Sleep

Sleep Baby Sleep Lucifer's Shadow

Lucifer's Shadow Season for the Dead

Season for the Dead The Seventh Sacrament

The Seventh Sacrament The Garden of Evil nc-6

The Garden of Evil nc-6 Juliet & Romeo

Juliet & Romeo A Season for the Dead nc-1

A Season for the Dead nc-1 The Fallen Angel nc-9

The Fallen Angel nc-9 Little Sister

Little Sister The Lizard's Bite nc-4

The Lizard's Bite nc-4 The Killing 2

The Killing 2 The Fallen Angel

The Fallen Angel The Sacred Cut

The Sacred Cut Carnival for the Dead

Carnival for the Dead The Villa of Mysteries nc-2

The Villa of Mysteries nc-2 Macbeth

Macbeth The Killing - 01 - The Killing

The Killing - 01 - The Killing The Villa of Mysteries

The Villa of Mysteries Dante's Numbers nc-7

Dante's Numbers nc-7 The Sacred Cut nc-3

The Sacred Cut nc-3 The Seventh Sacrament nc-5

The Seventh Sacrament nc-5