- Home

Page 2

Page 2

The Garden of Angels

The Garden of Angels Solstice

Solstice Death in Seville

Death in Seville A Season for the Dead

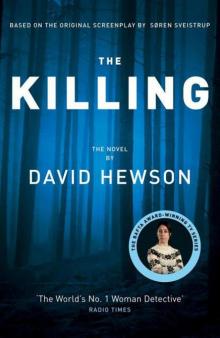

A Season for the Dead The Killing tk-1

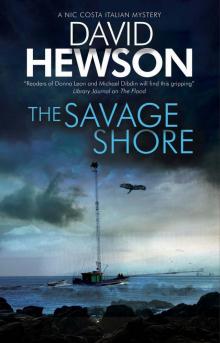

The Killing tk-1 The Savage Shore

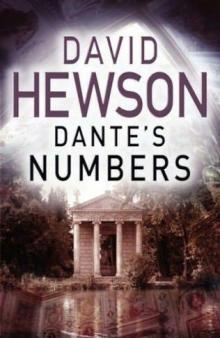

The Savage Shore Dante's Numbers

Dante's Numbers Sacred Cut

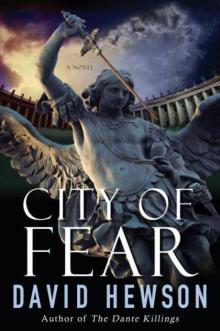

Sacred Cut City of Fear nc-8

City of Fear nc-8 The Blue Demon

The Blue Demon The Garden of Evil

The Garden of Evil The Lizard's Bite

The Lizard's Bite The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Sleep Baby Sleep

Sleep Baby Sleep Lucifer's Shadow

Lucifer's Shadow Season for the Dead

Season for the Dead The Seventh Sacrament

The Seventh Sacrament The Garden of Evil nc-6

The Garden of Evil nc-6 Juliet & Romeo

Juliet & Romeo A Season for the Dead nc-1

A Season for the Dead nc-1 The Fallen Angel nc-9

The Fallen Angel nc-9 Little Sister

Little Sister The Lizard's Bite nc-4

The Lizard's Bite nc-4 The Killing 2

The Killing 2 The Fallen Angel

The Fallen Angel The Sacred Cut

The Sacred Cut Carnival for the Dead

Carnival for the Dead The Villa of Mysteries nc-2

The Villa of Mysteries nc-2 Macbeth

Macbeth The Killing - 01 - The Killing

The Killing - 01 - The Killing The Villa of Mysteries

The Villa of Mysteries Dante's Numbers nc-7

Dante's Numbers nc-7 The Sacred Cut nc-3

The Sacred Cut nc-3 The Seventh Sacrament nc-5

The Seventh Sacrament nc-5