- Home

- David Hewson

The Fallen Angel Page 15

The Fallen Angel Read online

Page 15

The phone buzzed again.

‘Mina?’ he asked anxiously.

It was a message from a number he didn’t recognize. He stared at the words on the screen: ‘Meet me in the Campo. The Lone Star. Be alone. Robert Gabriel.’

THREE

Costa knew this place well, from work, not pleasure. It was one of the busiest bars in the Campo dei Fiori area: a grubby dive serving cheap alcohol to a predominantly international and young crowd. The Lone Star was where the students and backpackers from America and England congregated of a night. To drink, to flirt. To feel free of the restraints of home. He’d lost count of the fights he’d dealt with, the number of drug busts he’d seen recorded among its customers. All just a few short steps away from the plain, upright building that had once been home to the mistress of Alexander VI, the Borgia Pope, her presence still marked by a small crest on the wall of the house where Lucrezia and Cesare Borgia came into the world.

He wondered if any of the kids around him knew how much history lay just outside the door, and what the offspring of Rodrigo Borgia, no strangers to debauchery themselves, would have made of the Campo dei Fiori five centuries on. The bar was packed. A hundred youngsters or more. The music was deafening, the voices predominantly English: drunk, elated, expectant. He scanned the faces, looking for one that might jog a memory. Costa was aware that he hadn’t got a good look at Mina’s brother that night in the Via Beatrice Cenci. All he remembered was a tall figure, a head of bushy hair and that curious remark before the gunshot: She’s safe now. Words that had set him wondering in the first place.

After fifteen futile minutes he asked the barman if he knew an English kid called Robert Gabriel. No luck. After half an hour he was ready to go home. Then the phone beeped again. Not a call, just another text message: ‘I wanted to see you were alone. Meet me in the apartment. Via Beatrice Cenci. Fifteen minutes.’

He was here. He had to be. Costa found himself gazing across the sea of bodies again. He stopped at a tall figure in the far corner, near the side door that led to the little lane connecting the Campo with the Piazza Farnese. The kid was watching him, interested, maybe a little afraid. Robert Gabriel looked different somehow. Just as tall, and the hair was long, though a little lank, unwashed. His complexion was darker than Mina’s, his expression bleak and unintelligent. He was wearing a bleached denim jacket over a black T-shirt.

Costa shrugged at him as if to say: we could just talk here.

We could even talk on the phone, he thought.

But then he was gone, out through the side door into the street.

Costa got out as quickly as he could but it was no use. The ancient square, with its hooded statue of the executed monk Giordano Bruno at its centre, had taken on its night-time identity: loose and noisy. Watching the crowds of young men and women meandering between the bars he found himself wondering why Mina Gabriel had never thought to join her brother in this perennial ritual. It seemed easy, natural for the foreigners who came to Rome to study, to spend an enjoyable year pretending to be Roman before real life, with its cares and demands, came to claim them.

The sky was a dark sweep of velvet punctured by stars and the lights of passing aircraft. Fifteen minutes. He tried to call Falcone but the inspector was on voicemail. No one at the Questura would assemble any kind of support in the time he had. Either he went along with the invitation or he walked away from the whole affair, went back to the Vespa in Governo Vecchio, hoped the ancient carburettor had cleared enough to take him home.

He found himself thinking of Mina Gabriel, picturing her that night in the Via Beatrice Cenci, staring at him, needing something.

Costa pushed his way through the shifting, aimless throng in the Campo, and started to walk back towards the ghetto, a route that would, he realized, take him directly past the Palazzetto Santacroce from which she’d made that last, scared call, its message opaque and impeded by some intervention he failed to understand.

FOUR

The door to the building was open, the entrance hallway dimly lit with low security lights that wound up the long staircase like decorations left over from Christmas. He shouted the brother’s name. Costa’s voice echoed round and round the winding steps, dying somewhere near the summit. He recalled that long climb the previous day, with Peroni stopping to catch his breath on every floor.

The thought of making that journey again was starting to fill his head with dismay when a loud, metallic clang shook the floor beneath his feet. It took a moment to realize what it was. The lift, the small, old-fashioned open iron elevator with the out-of-order sign on the doors, was ascending from below with an asthmatic rusty wheeze.

One more lie, Costa thought as he listened to the rheumatic squeal of the cables and pulleys straining against one another. Then the cage arrived with a heavy, clattering bang. Nothing happened. He walked over and could see, in the dim light of the interior bulb, that it was empty. The buttons were within reach through the collapsible door. Someone had sent it for him.

He got in and waited. This was a vast, empty place. Robert Gabriel could be anywhere. After a few moments there was another rattling sound and the cage began to move uncertainly down, descending into the thick, airless dark, a dead space rank with the smell of damp and decay. Instinctively Costa patted his jacket, the empty spot where his gun would have been if he were on duty.

‘One of those days,’ he said to himself.

The lift came to a halt with a rickety jolt. The only thing visible was a single dingy light bulb dangling from a cord beyond the cage. He threw the door open with a clatter and got out, calling once more. Another light came on, then a third. His eyes began to adjust. The basement was full of building material. Sacks of cement, planks, a wheelbarrow, boards covered in hardened plaster. From somewhere in a far corner came the scurrying sound he associated with rats. Close by he could see a single heavy door which looked as if it might lead to some kind of ‘garden’ apartment, the accommodation that was always the cheapest in these places.

He walked ahead. There was a thin line of yellow light beneath the door.

‘Robert,’ he said calmly and turned the handle.

There was no reply. He walked in and found himself in what appeared to be a photographic studio. A small forest of professional-looking floodlights was set against one wall, several of them lit so they cast a dazzling white field of illumination across the room. They were all aimed in a single direction: at an ornate double bed covered in crumpled scarlet sheets, set against a wall decorated with a sea of cavorting cherubs, winged chubby creatures, the kind Raphael once painted, though not quite like this.

The tiny creatures, like miniature angels, leered lasciviously as they coupled and licked and squeezed and squealed on the cloudy pillows of a perfect blue sky, eyes down, always, to the bed beneath them.

Pornography, he thought immediately.

‘Robert,’ he called into the darkness, then realized he could smell something.

A memory returned. The forensic department when Teresa Lupo was just one more junior in a time before the world had turned entirely digital. The police photographers then used film, loved the stuff, would wind off frame after frame getting every angle of a victim, recording each death for posterity, unable to see the results until they returned to the Questura and ran their work through chemicals in the dark. Life before digital was finite, circumscribed by its own limits, by cost. No more than six films per case unless someone wanted more. Now, when photos and videos came for free, they could shoot to their heart’s content, fill the Questura’s screens with a million images, each demanding interpretation.

It was easier in some ways before. Paucity, the very fact that the information to which one had access was limited, could pull a complex investigation into focus. And focus smelled like this. There was a darkroom somewhere nearby, one of those small, enclosed places with sinks and mysterious equipment from which, with a little luck, a spark of enlightenment would emerge on the face of a damp piece

of photographic paper held between the teeth of a pair of plastic developing tongs.

If Robert Gabriel was there, on this hidden floor in the basement of the house in the Via Beatrice Cenci, he didn’t want to make his presence known.

Costa walked up to the bed and thrust aside the top sheet. The fabric beneath was freshly crumpled. There was the faintest trace of a stain, like the one next to the adolescent torso in the photo in Malise Gabriel’s book, the pale young skin that might or might not be Mina’s.

He took out his phone and glanced at the screen. No signal, not even a flicker. He was underground, deep in the belly of a stone fortress. The modern world didn’t want to intrude into this place.

His fingers fell on the stem of the nearest floodlight. Costa began to angle it around the room. The walls were bare. In the corner was a small and narrow door, just ajar. He took one step towards it and the chemical smell became stronger.

Acid. Fixer. Hypo. He hadn’t heard those terms in years but each one came with its own distinct scent as he remembered the times he’d spent in the darkroom, watching, waiting for some image to emerge on the paper as it swilled slowly in the plastic baths.

He got to the other side of the room and pushed his hand through. There was a black curtain, just as he expected. And somewhere beyond, the most precious, most dangerous thing of all in a darkroom, the string pulley for the light switch. One jerk on that at the wrong moment and any film, any unfixed print would be rendered useless in a second.

Costa remembered the way the Questura had a red light outside its own processing unit, warning anyone thinking of entering to stay out until the mystical process of turning invisible silver halide into some black and white representation of reality was complete. There was no such sophistication here. In the basement of the ancient palazzo, next to what gave every indication of being some kind of secret pornographic studio, perhaps there was no need.

His hand fumbled against the inside wall, hunting for the string. Nothing. He edged through a little further and something brushed against his face. It was always somewhere you didn’t expect it. Costa pulled the dangling cord, blinked briefly as two strong fluorescent tubes began to flicker violently into life above him, found himself walking forward in the brief flashes of illumination they afforded, then screamed, couldn’t help it, as his arm bumped into something, sent it swinging away like a pendulum that disappeared for a moment and came back, fetching up against his right cheek with the plain, heavy physicality of a corpse.

Cold skin, cold clothing, another, more organic smell, the stink of death.

The tubes hit full power. The room was awash with bright, cool light. His face was level with the chest of a human being moving gently in front of him. He looked up and found himself face to face with the dead features of Joanne Van Doren, her pale, thin features distorted by the rope around her neck, eyes bulging, tongue lolling, like the mask of a slaughtered clown.

‘Jesus,’ Costa whispered and tried to turn away.

The hard, metallic nose of a gun edged onto the back of his neck.

‘Keep looking,’ said a young English voice beside him. ‘At her. Not me.’

Costa fought to think, closing his eyes for a moment. Then, when he knew he had to look, he forced himself to stare at the dishes and the gear by the developing sinks, not the body swaying in the bright light just in front of him.

‘What do you want?’ he said finally.

‘I want you to see. I want you to understand.’

‘Understand what?’ he asked and tried to turn. It was easier to talk if you could see someone. ‘I can’t . . .’

‘Don’t look at me!’ the English kid screamed, and stabbed the gun hard into Costa’s skull.

Pain. Fear. Incomprehension.

‘What do you want, Robert?’ he repeated.

Strong fingers wound into his hair, forced him down over the evil-smelling sink.

‘Leave my sister alone,’ Robert Gabriel hissed in his ear. ‘This is nothing to do with her. Nothing. Tell them that.’

‘And you?’

‘What about me?’

He was scared. Angry. Full of the same petulant doubt Costa had witnessed in Mina at times.

‘Where are you going to go? With no money. No home.’ The pressure of the barrel on his neck eased. ‘Where are you going to run? With friends like yours, you’re a liability now. All they’re interested in is business, whatever they told you. Liabilities worry them. They won’t hide you. Not forever.’

The grip on his hair increased until it hurt. Robert Gabriel was strong.

A punch to the face, a blow with the body of the gun. Costa stumbled to the floor, lost his balance and found himself scrabbling on concrete.

‘I said, don’t look!’ the voice above him screamed.

He waited, listening to the steps recede into the studio beyond, and then disappear into the black maw of the building.

When there was silence Costa got up and went over to Joanne Van Doren. She’d been dead for a few hours. The rope went round a black heating pipe in the ceiling. Next to her was a plain chair, like the one in the studio, on its side on the floor, as if kicked there. He remembered the pained expression on her face when he came here the previous day. Perhaps he should have noted that more, asked someone to call. But she was just the owner of this block, not someone involved in the story. Or so it seemed.

‘I’m sorry,’ he murmured, and walked out of the corridor, found the stairs, went up them one by one, clutching the banister in the dark, watching his phone all the way, waiting for some sign that he was back in the world beyond once more.

PART SEVEN

ONE

Teresa Lupo looked at the corpse on the gurney in the basement studio, scratched her straight brown hair, screwed up her broad, pale face and said, ‘Well, I can tell you one thing, Leo. You’ve got your murder now.’

It was nine fifteen. Costa felt dog-tired after a few restless hours at home. Just before seven Falcone summoned him to the Questura for a questioning that carried much of the same mute aggression he would have used on any witness. Then a team of officers assembled, Peroni among them, and he was ordered to join them and the forensic team that was already working in the basement of the house in the Via Beatrice Cenci.

The morgue people had made up their minds long before Falcone arrived. Costa could see it in Teresa’s body language, the insistence with which she’d made them all climb into white bunny suits before setting foot inside the scene, the way she was getting her team to mark out the whole of the basement area. She’d been a fixture of the Questura for as long as Costa had been a cop, a bright, occasionally incandescent spark of intelligence, intolerant of laziness, generous to those she admired, kind and sympathetic to the bereaved who passed through her department. The relationship with Peroni, almost fifteen years her senior, had mellowed her somewhat. But no one would dare take her for granted.

‘You’re sure of that?’ the inspector asked.

She was a cautious worker, never one to rush to judgement. It was unusual for her to reach a conclusion before returning to the Questura and a careful consideration of all the options.

‘Absolutely. See for yourself.’

Peroni coughed and went to stand by the doorway leading back to the lift cage. Falcone and Costa joined her by the gurney. She was pointing at Joanne Van Doren’s neck. The insubstantial white nylon noose, washing line he guessed, had been removed to reveal a mass of livid bruises, more than Costa would have expected.

‘The technical term is “ligature furrow”,’ she said. ‘The mark the rope makes on skin, under pressure. If this woman had committed suicide by hanging herself I would have expected to see just one. Diagonal, like an inverted V. It’s there.’ Her gloved fingers traced the lines of some pinkish marks on the American woman’s neck running from her throat back into her scalp. ‘But it’s not alone, is it? She was already dead when she got that.’

Another strip of bruising ran horizontally around

her neck, joining the fainter one at the front, separate as it ran round to the back of her head, the two lines joined by what looked like grazed skin.

‘Horizontal furrows are what you get from strangulation. Someone . . .’ She stood up, turned her assistant Silvio Di Capua round, and made to slip an imaginary noose over his head. ‘. . . came up behind her, dropped the rope over her head, tightened it on her neck.’ A brief demonstration. ‘And pulled till she was gone. Then he ran the rope over that heating pipe in the ceiling and suspended her next to the chair he’d kicked over. That’s why we’ve got abrasions running from the original furrow to the one she got from being hanged like that. The rope dragged when she was hauled upright.’

‘He?’ Peroni asked.

‘Well,’ she said with a shrug. ‘Someone with a lot of strength, anyway. I’d guess a man. Asphyxiation is a man thing. Women tend to be either more direct or more subtle.’

Costa couldn’t quite work this out.

‘And then he tried to make it look like suicide?’

She nodded.

‘Pathetic, isn’t it? I can give you more proof once I have her back in the morgue. Really, you don’t need it. How anyone could think they’d get away with a trick like that, I can’t begin to imagine. I’ll take a look at the Englishman later on today and see what we can come up with there. But this one, I guarantee, is murder, pure and simple. I’d guess he wore disposable surgical gloves. You can smell the latex on the rope. If we’re lucky he dropped them somewhere around here. If we find them I can give you something from the lining.’

Falcone didn’t look terribly hopeful.

‘I want to go through this whole building,’ Teresa told him. ‘Floor by floor, room by room. Top to bottom. If we’d done that yesterday we’d have found this little secret studio of hers. Perhaps things would have turned out differently.’ She frowned at the corpse on the gurney. ‘Maybe if our American friend had been a little more co-operative and candid she’d still be alive.’

The Garden of Angels

The Garden of Angels Solstice

Solstice Death in Seville

Death in Seville A Season for the Dead

A Season for the Dead The Killing tk-1

The Killing tk-1 The Savage Shore

The Savage Shore Dante's Numbers

Dante's Numbers Sacred Cut

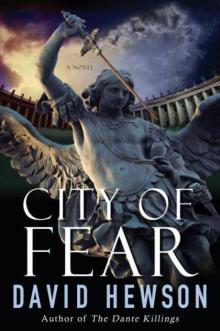

Sacred Cut City of Fear nc-8

City of Fear nc-8 The Blue Demon

The Blue Demon The Garden of Evil

The Garden of Evil The Lizard's Bite

The Lizard's Bite The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Sleep Baby Sleep

Sleep Baby Sleep Lucifer's Shadow

Lucifer's Shadow Season for the Dead

Season for the Dead The Seventh Sacrament

The Seventh Sacrament The Garden of Evil nc-6

The Garden of Evil nc-6 Juliet & Romeo

Juliet & Romeo A Season for the Dead nc-1

A Season for the Dead nc-1 The Fallen Angel nc-9

The Fallen Angel nc-9 Little Sister

Little Sister The Lizard's Bite nc-4

The Lizard's Bite nc-4 The Killing 2

The Killing 2 The Fallen Angel

The Fallen Angel The Sacred Cut

The Sacred Cut Carnival for the Dead

Carnival for the Dead The Villa of Mysteries nc-2

The Villa of Mysteries nc-2 Macbeth

Macbeth The Killing - 01 - The Killing

The Killing - 01 - The Killing The Villa of Mysteries

The Villa of Mysteries Dante's Numbers nc-7

Dante's Numbers nc-7 The Sacred Cut nc-3

The Sacred Cut nc-3 The Seventh Sacrament nc-5

The Seventh Sacrament nc-5