- Home

- David Hewson

The Wrong Girl Page 14

The Wrong Girl Read online

Page 14

‘Ismail Alamy’s been in custody for eighteen months. He can’t have had anything to do with what happened in Leidseplein. We’re looking into that. I can’t elaborate. You wouldn’t expect me to. Unless you’ve reason to believe he had some connection—’

‘I shed blood for this country,’ Pijpers cut in, tapping at his chest, coffee spilling all over the table. ‘I saw what these animals are like when you let them loose. All the same. They’ll kill you as soon as draw breath. Fucking ragheads—’

‘Whoa, whoa, whoa,’ Koeman interrupted. ‘You can’t go around talking like that. We’ve got sensitivities these days. And besides . . .’ This was true and worth saying. ‘Most of the bad men I’ve met think they’re good Christians. Or Muslims. Or whatever. People like Alamy . . . like that kid AIVD shot on Sunday . . . they’re just the lunatic fringe.’

‘You’re a fool,’ Pijpers told him. ‘All of you. Clueless. No idea what’s round the corner.’

Koeman glanced at his watch then back at the stairs to his office. There was real work still to be done.

‘Which is what?’

‘Sharia courts. Treating our women like scum. Telling us what to do in our own country’ He tapped his forehead. ‘I’ve seen it. I know what it looks like.’

Koeman sighed and briefly closed his eyes.

‘We’re really busy right now. Chasing the very things you think we should be looking at. Bad people. Ours. Theirs. Sometimes a little of both.’

‘Idiots,’ Pijpers added.

‘Reception called me down because you told them you had something useful to tell us. I would be really grateful if you could pass that on. Then go back to talking to Mr Heineken and his friends. Because frankly they’re probably better listeners than me right now.’

There, he thought. The nice-guy act didn’t last.

‘You can’t let that bastard Alamy back out on the street. I know these people. Better than you ever will. I’m done listening to monkeys. I want to talk to your boss.’

‘About what?’

Pijpers brushed down his old, battered suit as if getting ready for a job interview.

‘That’s for him to hear.’

He took the ancient and smelly pipe out of his pocket, sucked on the end, then pulled out a can of tobacco.

‘I’m waiting,’ Pijpers said.

‘You’re not actually. And you’re not lighting that stinking thing in here either. If you’ve got something to say you can say it to me.’

The man glared at him. Then he muttered a curse and got to his feet.

‘I should have known I was wasting my breath on you morons,’ he muttered with the pipe still stuck between his teeth.

Koeman tried to smile.

‘I really recommend you try one of the charities. If you like I can find you some names. A number.’

‘I don’t need your pity. You know what I did in the army?’

‘I can guess.’

‘No, you can’t. I was military intelligence. I did your job. Only better.’

Koeman stood up, took out a twenty note and waved it in front of Pijpers’s unwashed, surly face.

‘Promise it goes on food. Not booze or something worse.’

The man just stared at the money.

‘Cretins. Shit for brains.’

‘Well I tried,’ Koeman sighed and watched him go.

Henk Kuyper took them to the first-floor dining room. Through the long windows they could see the playground across the street. His wife sitting glumly on her own. Saskia barely talking to the other kids.

‘You want me to fetch them?’ he asked. ‘I have to say I’m getting really sick of this. Shouldn’t you be looking for that child?’

‘We are,’ Bakker said and sat down.

Vos glanced at her, a look that said, ‘Mind the tone.’

Then took the chair opposite Kuyper and asked him what he did. The answer didn’t add up to much. Environmental consultancy. Liaison. On the side he offered voluntary political advice for anyone who needed it. He made it clear that money wasn’t his first concern. He came from a ‘good’ family. Finances weren’t a problem.

‘You volunteer for radical causes?’ Bakker butted in. ‘People like Ismail Alamy?’

‘I support people the rest of you ignore. I don’t pick and choose on the basis of religion. Or skin colour.’

‘Didn’t answer the question,’ she pointed out.

He frowned.

‘I’ve never worked on Alamy’s case. A few similar. But not that one.’ He stared straight at her. ‘But if his lawyers had come to me I’d have done what I could. From what I’ve read we’ve no reason to hold him. Or to hand him over to people whose idea of justice comes nowhere close to our own. If they were our enemies we’d never dream of it. So why change when they’re supposedly our allies?’

Neither answered. He smiled a sarcastic smile and said, ‘It’s OK. I wasn’t expecting a response on that one. You do your job. I know. That’s all that matters.’

‘As best we can,’ Vos answered. ‘The thing is you weren’t always on the side of the oppressed were you, Henk?’

The tall man in front of them wasn’t smiling any more.

‘In fact you were, in their terms, an oppressor. You worked for AIVD as one of their agents.’ Vos paused, watched him closely. ‘What happened?’

‘I’m a Kuyper. We’re a military family. Going back generations. I was pushed into that job. Wasn’t even asked about it.’

‘And then you leaked something to the papers and they kicked you out?’ Bakker added.

He thought about his answer, shrugged and said, ‘There are things the public have a right to know. AIVD came to accept that. I was never prosecuted. Never named in public’ He gazed at them both. ‘You shouldn’t be aware of this. It’s classified.’

‘There’s a missing girl out there,’ Laura Bakker told him. ‘We’re turning over every stone to find her.’

‘No stones here,’ he said easily. ‘I worked for AIVD for two years. My father got me the job. I didn’t have much choice. What I saw there . . .’ He stopped, frowned. ‘Do we really have time for philosophical discussions?’

‘So what you saw in AIVD turned you?’ she asked. ‘Radicalized you? Just like that British kid your former colleagues shot two days ago?’

‘Not quite like that,’ he answered with an edge. ‘But I saw things . . . learnt things . . . that altered my view of the world. We fool ourselves we’re a liberal democracy. It’s a lie. The richer get richer. The poor get poorer. And all the time we turn our backs on those who need us. If—’

‘We don’t need the lecture, Henk,’ Bakker interrupted. ‘We’re looking for a missing girl. The daughter of a Georgian sex worker. We’re not turning our backs. Where were you when Saskia went missing?’

‘I was on my way to Leidseplein,’ he said. ‘Renata was pissed off with me because I didn’t have time to see the parade earlier. I thought I’d try to make it up. I was just getting there when she called and said she’d lost her.’

‘And then?’ Vos asked.

‘Then I looked around and found her. I was fortunate I guess. So was Saskia.’

‘Good fortune,’ Bakker murmured.

‘Exactly,’ he agreed.

‘Was it good fortune that made you give Hanna Bublik that pink jacket?’ Vos added, watching him, following every move, every tic. ‘After you’d paid her for sex? A second time?’

A long moment. Henk Kuyper looked at him, at Bakker, then returned to Vos. And laughed. Just for a second.

‘She saw me, didn’t she? Going into Marnixstraat yesterday? I should have guessed.’

He got up, glanced outside at the playground. Saskia was playing finally, with a little boy. Bossing him around it looked like. Her mother sat and watched, clutching a paper cup.

‘Coffee,’ he said and went into the kitchen.

One customer. A surly American kid who didn’t know what he wanted and haggled over everything. Hanna Bubl

ik saw him off in twenty-five minutes, waited another quarter of an hour. No one passed her window except a street cleaner picking up stray beer cans from the night before.

She was prevaricating and knew it. So she wrote off the remaining three hours she had on the cabin, got dressed and walked outside.

A beautiful early winter day in Amsterdam. The remorse hit her straight away. She’d have taken Natalya down to the canal and fed the ducks. Watched her play in the park. Bought chips and sauce in little paper cornets, eaten them in the street.

Instead she walked across town to the main red-light district, cast a professional eye on the girls working there. More business in this part of the city. A higher price to seek trade here too. Different people to negotiate with. At least in Oude Nieuwstraat she knew mostly where she stood.

Spooksteeg was quiet at this time of the morning. She rang the bell on Yilmaz’s building and waited for an answer. It took a while. Then she was buzzed in and took the lift to the top floor, wasn’t surprised this time when it opened directly into his living room.

The Turk was half-naked in baggy trousers, his barrel chest covered in what looked like oil. He wasn’t alone. There was a muscular blond man in the same room. Younger. Covered in sweat and oil too. Both of them breathless.

She stared. The younger man had the most extraordinary tattoos all over his torso. A pair of eyes on his stomach either side of his navel. A skull in a basket on his right shoulder. A bleeding heart inside a triangle on his back.

‘We’re not finished,’ Yilmaz said when she started to speak. ‘You can wait.’ He grinned. ‘You can watch.’

There was a mat on the floor in front of the roaring fire. The Turk went back and gripped the younger man by the neck, fat, strong arms round his sinews. Then the two of them started to wrestle.

She’d seen things like this in Georgia too. Big, strong men trying to prove themselves. Was it sexual? She didn’t know. Or watch much. It went on for a while, grunting, one on top of the other, elbows, fists, fingers grabbing for purchase on slippery skin. Then Yilmaz twisted the other one round and threw him hard to the mat. The young man’s hands went up in surrender. The Turk laughed, got to his feet, slapped his big tanned belly.

‘Dmitri, Dmitri,’ he complained. ‘You make it too easy for me.’

The blond said something in what sounded like Russian. A language that always sent a shiver down Hanna’s spine. Then he got up and smiled like a young boy waiting for a present, picked up a towel and rubbed himself down. Some of the sweat and oil disappeared. He glanced towards what looked like a bathroom.

‘Shower in your own time,’ Yilmaz ordered then glanced at Hanna. ‘We’ve got business.’

He walked to the desk and opened the drawer stuffed with money. Some notes came out and he handed them over to Dmitri.

‘Half price,’ the Turk said. ‘You gave in too easily. You let me win.’ A grin. ‘And the rest I get for free.’

The Russian’s smile vanished but he didn’t argue. Then Dmitri found some clothes and left. Yilmaz disappeared into the bathroom and came out wearing a white fluffy robe, two cans of health drink in his hand. He told her to sit down and gave her one. Something with pomegranate.

‘Any news?’ he asked from the leather sofa.

‘No. I was wondering if . . . if you’d heard something.’

The big shoulders shrugged.

‘I told you, Mrs Bublik. I’m willing to help but I need you in my family. A man doesn’t protect strangers. We need some give and take here.’

‘You said you’d ask. My daughter’s been kidnapped!’

He sighed.

‘Yesterday you say the same thing. Yet this morning you’re working again. Trying to take a few euros from some passing fools in Oude Nieuwstraat. Really—’

‘Are you spying on me?’

‘I own those buildings. I keep an eye on my investment.’

She thought of the way someone had broken into their bedroom. Chantal’s guilty look that morning, and the news that Jerry was looking for more rent.

‘Is the dump I live in yours too?’ She wondered whether to say it. ‘Can you come and go as you please?’

He waved a dismissive hand.

‘I’ve lots of interests. More than you can imagine. This is irrelevant. You need your daughter home. I can appreciate that.’ He swigged at the can and leaned back on the shiny sofa. ‘I’ve asked questions. Even though you’ve offered me nothing.’

She waited.

‘There are evil men in this city. They call themselves devout. They’re not.’

‘What did you hear?’

‘Only gossip. Nothing worthwhile. If you want me to help you know what you need to do.’

A phone trilled on the desk. He went to answer it. Glanced at her, put his hand over the mouthpiece and said, ‘I need to deal with this. Stay here.’

Yilmaz walked through the door at the end of the room. She heard his big feet padding down what sounded like a long corridor. Gone. For a while anyway.

Stealing was bad. It was something she’d never done. But now . . .

She got up and walked to the desk. He displayed this money to everyone, she thought. It was his way of saying, ‘I’m king here. I live to my own rules.’

The door to the corridor was half open. She could hear his voice. Almost distant. He was speaking Turkish or something. Loud and commanding.

She opened the drawer and stared at the money. Did he know how much was there? Would he even miss a thousand?

Hanna picked up a few fifty euro notes and felt odd and dirty. Money was to be earned, always. However that was done.

But she snatched at some anyway and stuffed them in her pocket. The stacks of notes moved. At the back there were other things there. Watches. Phones. Wallets.

And something silver glinting, an amber pendant attached to the chain. Cheap but beautiful. To her anyway.

The necklace her husband had given her that night they were married in distant Gori. She touched the chain, the glassy brown and yellow stone.

Stolen when someone broke into the gable room she’d shared with Natalya.

There was a gun beyond it and a pack of ammunition, right at the back, like an afterthought. Dusty as if the weapon was there for an emergency and hadn’t been needed in years. Cem Yilmaz ruled this world. He had others to protect him.

Footsteps down the corridor. The sound of a phone conversation coming to an end.

She let go of the necklace, reached out and snatched the weapon and the pack of shells, fumbled them into her pocket, closed the drawer, walked quickly back to the centre of the room and took the chair.

Yilmaz marched in and stared at her.

‘A good man would help me,’ she said, just to get out some words.

‘A good man will. When you’re ready.’

He glanced at the desk. The drawer was shut. Was it like that before? She didn’t feel sure. Perhaps he was in the same position.

‘Are you, Mrs Bublik?’

He broke into their room when she was out dealing with the police. Stole everything she had to force her into his clutches. She’d never fired a gun in her life. Would have to go to an Internet cafe to learn how to use one. But she knew this was not the time. Cem Yilmaz was a big-time gangster in the city. He surely heard things that never reached the police.

‘Not yet,’ she said and got up, aware, and a little frightened, that this clearly left him furious.

There was a street cleaner working in Spooksteeg. Sweeping up rubbish, putting down disinfectant. The place stank. Hand shaking, with trembling fingers, she turned to face the wall and placed the gun and the cardboard box of ammunition deep inside her bag. Then took out her phone.

No messages.

Three cups of macchiato on the table. Bakker didn’t touch hers. Vos pushed his to one side. The sun was bright outside. They could just hear children’s voices rising from the playground.

‘What do you want me to say?’ Kuyper asked fi

nally.

‘The truth would be nice,’ Bakker suggested.

He looked at her and laughed. Then turned to Vos.

‘Is she always this . . . rough at the edges?’

‘Seems a reasonable enough request to me,’ Vos told him. ‘If you like I can arrest you and we can carry on this conversation in Marnixstraat.’

‘Arrest me for what?’

‘You’ve got extremist sympathies,’ Bakker cut in. ‘You used to work for AIVD. You slept with Natalya Bublik’s mother then gave her the jacket that got her kidnapped. You checked out she was going to be in Leidseplein. Don’t you think that’s enough?’

‘What do you mean I checked out where she’d be?’

‘That’s what she said,’ Vos replied.

‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ he said and casually sipped at the coffee. ‘Maybe I asked what she was doing with her kid that Sunday. That’s all. And my opinions are entirely legal by the way. What I did in the past’s irrelevant. It’s not illegal to have sex with a prostitute. If it was your jails would be full.’

‘And the jacket?’ Bakker asked.

He put down the cup and stared at her.

‘How old are you?’

‘Is that relevant?’

‘To me it is.’

‘Twenty-five.’

‘I’ve got ten years on you. Long years. Things change.’ He closed his eyes for a moment and looked briefly fragile. ‘The news said Alamy’s going free. The court’s going to let him walk. Is that true?’

‘Possibly,’ Vos answered. ‘Until the ruling’s released we don’t know.’

‘He’ll let her go then, won’t he?’ he said, a note of hope in his voice. ‘I mean . . . why would he keep her?’

‘We don’t know.’ Bakker was getting cross and that always worried Vos. ‘We can’t stop searching for her, can we?’

Vos looked round the room.

‘You’ve got such a nice life, Henk. Money. A fine home. A family. Why wander into the red-light district and poke your nose in one of those cabins? I’m interested. It won’t go any further.’

The Garden of Angels

The Garden of Angels Solstice

Solstice Death in Seville

Death in Seville A Season for the Dead

A Season for the Dead The Killing tk-1

The Killing tk-1 The Savage Shore

The Savage Shore Dante's Numbers

Dante's Numbers Sacred Cut

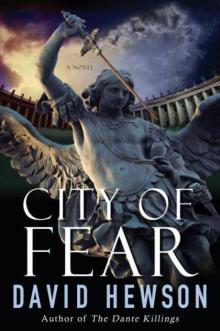

Sacred Cut City of Fear nc-8

City of Fear nc-8 The Blue Demon

The Blue Demon The Garden of Evil

The Garden of Evil The Lizard's Bite

The Lizard's Bite The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Sleep Baby Sleep

Sleep Baby Sleep Lucifer's Shadow

Lucifer's Shadow Season for the Dead

Season for the Dead The Seventh Sacrament

The Seventh Sacrament The Garden of Evil nc-6

The Garden of Evil nc-6 Juliet & Romeo

Juliet & Romeo A Season for the Dead nc-1

A Season for the Dead nc-1 The Fallen Angel nc-9

The Fallen Angel nc-9 Little Sister

Little Sister The Lizard's Bite nc-4

The Lizard's Bite nc-4 The Killing 2

The Killing 2 The Fallen Angel

The Fallen Angel The Sacred Cut

The Sacred Cut Carnival for the Dead

Carnival for the Dead The Villa of Mysteries nc-2

The Villa of Mysteries nc-2 Macbeth

Macbeth The Killing - 01 - The Killing

The Killing - 01 - The Killing The Villa of Mysteries

The Villa of Mysteries Dante's Numbers nc-7

Dante's Numbers nc-7 The Sacred Cut nc-3

The Sacred Cut nc-3 The Seventh Sacrament nc-5

The Seventh Sacrament nc-5