- Home

- David Hewson

The Seventh Sacrament Page 11

The Seventh Sacrament Read online

Page 11

The slaughterhouse owner opened the door and instantly the smell and the light hit them. The place reeked of meat and blood and the overwhelming stench of urine. Rows and rows of bright spotlights, like batteries of miniature suns, ran across the ceiling. Once his eyes had adjusted, Costa found the hall was empty, save for one lone individual at the far end, sweeping what looked like a grubby tide of brown water into a central lowered drainage channel.

“You’re lucky,” Calvi told them. “We’re between consignments. But…”—he made a deliberate show of staring at his watch—“there’s a truckload outside that has to come through in thirty minutes. I’m warning you. Now I have to do paperwork. You talk to Enzo on his own. These cons don’t like it if the rest of us are around when they get reminded of things.”

Somewhere outside, there was the sound of a horse, whinnying. It was a scared sound, high and loud, the cry of a creature pleading for comfort. Then a rattle of angry hooves on wood.

They all went quiet.

“You get used to it after a while,” Calvi added, then limped away, leaving them on their own.

THE FOUR OF THEM WATCHED AS CALVI WENT INTO A SMALL office next to the entrance. It had one window looking out directly onto what Costa took to be the production line of the slaughtering floor: live animals came in at the far end, were stunned, killed, then hung on a moving chain and progressively butchered as the corpses travelled down the hall.

Teresa shaded her eyes against the burning lamps in the ceiling, looked up at the mechanism that moved the carcasses along, took hold of one of the big hooks and said, “Exhibit number one, gentlemen. It was one of these that put that hole in Toni LaMarca’s back.”

Peroni blinked at the long hallway. “There’s got to be a hundred of them at least. And…”

A series of smaller adjoining rooms, with the same white clinical look and blazing lighting, ran off from the opposite wall. Sides of red and fatty marbled meat hung on them.

“…the rest. It’s so bright in here.”

“When you’re dealing with dead things, you need to see what you’re doing,” Di Capua muttered. “I’m looking,” Teresa’s assistant added, then walked across the hall, surreptitiously pulling on a pair of white plastic gloves as he did so.

The figure under the last set of lights stopped pushing the huge broom and glanced back at them, uncertain at their approach. The tide of grubby water at his feet swelled slowly round his boots then continued down to the channel at the centre of the hall.

“Enzo!” Peroni shouted. The other man nodded. They walked over. Costa showed his badge.

“First-name terms,” the man muttered. “This must be bad.”

Enzo Uccello was a short, skinny man with a gaunt face, prominent teeth, and thoughtful eyes. He looked in his mid-thirties, and a little worn down by life.

“We need help,” Costa told him. “When did you last see Giorgio Bramante? And where were you last night?”

Uccello muttered something under his breath. Then…

“Giorgio went off shift here yesterday at three. I haven’t seen him since. Last night I stayed in, drank my one regulation beer—which is as much as I can afford—and watched TV. On my own, before you ask.”

He had that easy, glib way of answering questions any cop recognised. He’d been through this before.

Costa was getting interested. “Where do you live, Enzo?”

“Testaccio. The same block as Giorgio. The prison people have some kind of deal.”

Teresa stared at him. “And you didn’t see him?”

“Signora,” Uccello sighed. “Giorgio and I shared a cell the size of a dog kennel for the best part of eight years. I respect the man. He should never have been in jail. He never would have been, if you people knew what you were doing. But after all that time together it’s nice to spend a little while apart. Trust me.”

“I can see that,” Peroni agreed genially. “Did he tell you he was still angry? Was he looking for some kind of payback?”

“What?”

“Giorgio killed someone last night. One of the students who was under suspicion for his son.”

“Oh no…” Uccello murmured. He had been working all day, Costa guessed. He hadn’t heard.

“This wasn’t the first either,” Peroni went on. “Are you sure he didn’t mention anything?”

The ex-con threw down the broom. The grubby water spattered them all.

“No! Listen. I’m on conditional release. If I just fart at the wrong time, they put me back in that stinking place. I know nothing about what Giorgio’s been doing. That’s his business. And yours, if you say so. Nothing to do with me. Nothing.”

They didn’t press it. Uccello was sweating. Peroni had that look on his face Costa recognised; the big cop didn’t like pushing people, not unless there was a good reason. And if this was an act, it was a good one. Uccello seemed like someone who seriously wanted to avoid going back to prison.

“What did you do?” Peroni asked. “We can find out easily enough. I’d just like to hear it from you.”

The younger man spat on the floor, then picked up the broom and moved it around aimlessly. He didn’t look at them.

“I came home and found the neighbourhood loan shark screwing my wife. So I shot him.”

Peroni grimaced. “Bad…”

“Yeah. Got worse when you people came round and found out I was also the neighbourhood dope dealer, too. So don’t go feeling too sorry for me. But Giorgio…he’s different. He never belonged in that place. I was heading there all along. Now I’m out and staying out. Even if it means sweeping up blood and shit in here for the rest of my life. Any more questions? We’ve another bunch of animals to deal with soon.”

“There’s just the two of you here? And Calvi?” Teresa asked.

“It’s a small business these days. We’ve got two more men on shift when it comes down to the butchering. But first…”

He didn’t need to say it. She cast a long, quizzical glance down the room.

“How do you kill them?”

“Same way you kill most big animals.” He put a finger to his forehead. “Captive bolt to the forehead. Bang…”

She looked unsure of his answer. “What does that do?”

“Makes a hole through the skull into the brain.”

“And then it’s dead?”

“No. Then it’s unconscious. I have to stick it. Open a vein in its neck. Five minutes or so, then it’s dead.”

“The bolt goes through the skull?” Teresa asked.

“Correct.”

She scanned the room again, unhappy.

“And the rest,” she persisted, “you just do with knives?”

“And saws. It’s a process. Most people don’t want to know about it. Is there something in particular you’re looking for?”

Teresa Lupo shook her head. “Just a way of tearing a hole in a man’s heart without doing the slightest damage to his rib cage. There has to be something else.”

Costa had watched Silvio Di Capua work his way through the three adjoining smaller halls, looking progressively more miserable as he passed through each.

“What happens in there, Enzo?” he asked.

“You start off with a live horse,” Uccello explained with mock patience. “Then you get a dead one. Once it’s hung for a while, it moves down the line, and the further it goes, the smaller it gets. Over there we start packing it. Making it the kind of shape people can buy without thinking about what it used to be. Is this useful?”

Costa tried to focus on something that was hovering at the edges of his memory. “And the bones? What do you do with the bones?”

Uccello shrugged. “Not our job. They just go. Someone takes them away. After…”

Something occurred to Costa. “After what?” he prodded.

Uccello walked into the third room, the one Di Capua had just vacated. They followed. It seemed cleaner than the rest, washed down more recently. There was a small line of hooks in the ce

iling, but this time they were fixed, not attached to some kind of production line.

“Have you ever heard of ‘mechanically recovered meat’?” Uccello asked.

“You know,” Peroni grumbled, “if I hear much more of this, I’m going vegetarian too.”

Uccello almost laughed. “Don’t worry. It doesn’t go into humans. Not anymore. It’s for dog food, cat food. Animal meal. That kind of thing.”

“‘Mechanically recovered meat’?” Teresa asked.

“We butcher them by hand, as much as we can. When that’s done, you’d think there wasn’t much left on the carcass. There is. Sinew. Gristle. A little meat even. You can’t get it off with a knife. You need something more powerful.”

Silvio Di Capua was one step ahead of Costa. There were three long lances on the wall, each with an accompanying pair of stained gloves, face mask, and goggles. He took down the nearest lance and played with the trigger.

“Don’t mess with that….” Uccello was saying.

Some kind of device kicked in from outside, making a loud mechanical whirring noise. The lance leapt violently in Di Capua’s hand. A hard, thin stream of water shot out of the end of the device and flew straight to the opposite wall, a good eight metres away, with sufficient force to cover them all in a fine, cold spray.

“Water,” Teresa exclaimed, laughing. “Water!”

“Yeah,” Uccello agreed. “Water. We couldn’t use this room this morning for some reason. The drain was blocked. It wasn’t running away properly.”

Teresa cackled again. Then, before Costa could say a thing, she’d walked along the channel, found the sump where it ended, and was down on her knees, right sleeve rolled up, reaching down with her hand, deep into the gulley.

“As the man who shares your bed, I would really prefer it if you wore gloves for that,” Peroni said quietly. He looked as white as a sheet.

So did Uccello when his boss stormed into the room. Calvi was incandescent with rage.

“What the hell is this?” he yelled. “I let you in to talk to one of my employees. Next thing I know you’re messing around with the equipment. Get out of here! Enzo! What are you doing, man?”

“I just…”

There was fear on Uccello’s face. Fear of Calvi. Fear of doing something that could end his fragile freedom.

“I want you people gone,” Calvi bellowed. “You have no right. Out of here. Now!”

Teresa got up from the floor and came back to them, standing close to the slaughterhouse owner, so close he flinched. She had something in her hand. Now Costa flinched. Grey flesh. White tissue. Unmistakable hanks of dark, wet hide.

“What kind of horses do you kill here?” Teresa asked.

Calvi glowered at her. “Whatever I get sent! Whatever you people feel like eating tomorrow.”

“Nobody’s going to be eating anything that comes through here for a very long time,” she said. “This is a murder scene. Silvio. Call in. Seal everything. I don’t want any civilians in here until I’m done. No horses either.”

“What?” Calvi yelled. “I’m struggling to make a living as it is! You can’t do this! Why?”

She pulled a piece of tissue out from the mess in her fist, something white, very white, washed clean, as if it had been sitting in water for hours. It was a segment of skin, just big enough to fit in the palm of a hand. In the centre was the unmistakable brown circular shape of a human nipple.

“Because,” she went on calmly, “sometime last night Giorgio Bramante came back here with a man who’d rather have been anywhere else in the world. He beat him. He put him on one of those hooks up there, then hoisted him off the floor. And after that, while he was still alive, he hosed his heart out.”

Calvi had turned the same colour as Peroni. Both of them looked ready to vomit.

“That,” Teresa added, “is why.”

IT WAS GETTING DARK BY THE TIME FALCONE FINISHED AT Santa Maria dell’Assunta. Perhaps it was age or his convalescent state. Whatever the reason, Falcone found he had, for the first time, to make a conscious effort to list on a notepad what had to be done in order to make sure all the threads stayed in the head. There were many—some from the present, some from the past. And practical considerations, too. Falcone had sent an officer to his apartment to fetch some personal things for the enforced stay inside the Questura. Then he’d ordered copies of the most important Bramante files to be e-mailed to the Orvieto Questura, printed out, with a covering note he’d dictated, and sent to await the arrival of Emily Deacon at the house of Bruno Messina’s father. Cold cases—and too many aspects of this were cold—required an outside eye. Emily had the analytical mind of a former FBI agent. She also had no personal ties to what had happened fifteen years before.

The one person who wouldn’t be pleased was Nic Costa. Falcone felt he could live with that.

After despatching those commands, he’d made several careful walks around the crypt, thinking about Giorgio Bramante, trying to remember the man, trying to begin to understand why he would return to this place, so close to his family home, to perform such a barbaric act.

Remembering wasn’t easy. What he’d told Messina was true. Bramante had offered them nothing after his arrest, nothing except an immediate admission of guilt and a pair of hands held out for the cuffs. The man never tried to find excuses, never sought some legal loophole to escape the charges.

It was almost as if he were in control throughout. Bramante was the one who’d called the police to the dig on the Aventino when his son went missing. He had readily acceded when Bruno Messina’s father had allowed him the chance to talk to Ludo Torchia alone.

Falcone remembered the aftermath of that decision: the student’s screams, getting louder and more desperate with every passing minute, as Bramante punched and kicked him around the little temporary cell, in a dark, deserted subterranean corner of the Questura, a place where only a man told to sit directly outside would hear. Those sounds would stay with Leo Falcone always, but the memory offered him nothing, no insight, no glimpse into Giorgio Bramante’s head whatsoever.

The man was an intelligent, cultured academic, someone respected internationally, as the support Bramante gained when he came to court demonstrated. Without an apparent second thought he had turned into a brutal animal, ready to bludgeon a fellow human being to death. Why?

Because he believed Ludo Torchia had killed his son. Or, more accurately, that Torchia knew where the seven-year-old Alessio was, possibly still alive, and refused, in spite of the beating, to tell.

Falcone thought of what Peroni said. Any father would have felt that way.

Falcone had listened to those screams for the best part of an hour. If he’d not intervened, they would have gone on until Torchia died in the cell. It hadn’t been a desperate outburst of fury. Bramante had methodically pummelled Ludo Torchia into oblivion, with a deliberate, savage precision that defied comprehension.

A memory surfaced. After Torchia was pronounced dead, when the Questura was in an almighty panic wondering how to cope, Falcone had found the presence to think about Giorgio Bramante’s physical condition and asked to see his hands. His knuckles were bleeding, the flesh torn off by the force of the blows he’d rained down on Torchia. On a couple of fingers, bone was visible. He’d needed stitches, serious and immediate treatment. Weeks later his lawyers had quite deliberately removed the bandages from his hands for each court appearance, replacing them with skin-coloured plasters, trying to make sure the public never saw another side to the man the papers were lauding, day in day out. The father who did what any father would have done…

“I don’t think so,” Falcone murmured.

“Sir?”

He’d forgotten the woman was still around, seated in a dark corner of the van, awaiting instructions. Rosa Prabakaran had, somewhat to Falcone’s surprise, earned his approval after Teresa Lupo talked her back onto the case. The girl was quick, had a good memory, and didn’t ask stupid questions. In the space of a couple of ho

urs, she’d touched base on several important points, most importantly in liaising with intelligence to see what else could be gleaned from existing records. There was little there. Dino Abati had left Italy a month after Bramante went to jail, abandoning what had been a promising academic career. Perhaps Giorgio Bramante had tracked him down somewhere already, found him in the dark, done what he felt was right in the circumstances. Falcone wondered if they’d ever know.

Focus.

He’d lost count of how many times he’d said that word to a young officer struggling to come to terms with an overload of information, a succession of half-possibilities just visible in the shadows. Now Leo Falcone knew he needed to heed his own advice. He was out of practice. His brain hadn’t worked right since he’d been shot. Everything took time. The delightful presence of Raffaella Arcangelo had clouded his judgement, made him forget what kind of man he was, how much he’d been missing work all along. It was time to put matters right.

He looked at Rosa Prabakaran. “Make sure intelligence keeps looking. They’ve got to have more than this.”

She nodded. “How do we find him?”

It was such an obvious question. The kind you got from beginners. Falcone felt oddly pleased to hear it.

“Probably we don’t. He finds us. Giorgio Bramante is looking for something or someone. That’s the only thing that will make him visible. When he’s not looking, he’s probably untouchable. He’s too clever to have left any obvious tracks. To stay with people he knows.”

The Garden of Angels

The Garden of Angels Solstice

Solstice Death in Seville

Death in Seville A Season for the Dead

A Season for the Dead The Killing tk-1

The Killing tk-1 The Savage Shore

The Savage Shore Dante's Numbers

Dante's Numbers Sacred Cut

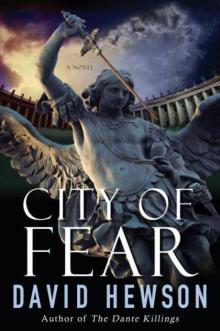

Sacred Cut City of Fear nc-8

City of Fear nc-8 The Blue Demon

The Blue Demon The Garden of Evil

The Garden of Evil The Lizard's Bite

The Lizard's Bite The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Sleep Baby Sleep

Sleep Baby Sleep Lucifer's Shadow

Lucifer's Shadow Season for the Dead

Season for the Dead The Seventh Sacrament

The Seventh Sacrament The Garden of Evil nc-6

The Garden of Evil nc-6 Juliet & Romeo

Juliet & Romeo A Season for the Dead nc-1

A Season for the Dead nc-1 The Fallen Angel nc-9

The Fallen Angel nc-9 Little Sister

Little Sister The Lizard's Bite nc-4

The Lizard's Bite nc-4 The Killing 2

The Killing 2 The Fallen Angel

The Fallen Angel The Sacred Cut

The Sacred Cut Carnival for the Dead

Carnival for the Dead The Villa of Mysteries nc-2

The Villa of Mysteries nc-2 Macbeth

Macbeth The Killing - 01 - The Killing

The Killing - 01 - The Killing The Villa of Mysteries

The Villa of Mysteries Dante's Numbers nc-7

Dante's Numbers nc-7 The Sacred Cut nc-3

The Sacred Cut nc-3 The Seventh Sacrament nc-5

The Seventh Sacrament nc-5