- Home

- David Hewson

The Wrong Girl Page 10

The Wrong Girl Read online

Page 10

‘You know about the case?’ Vos asked.

‘Enough. You don’t have a shred of evidence he’s committed a crime here. Just because he says things you don’t like you want him extradited to a country that doesn’t even pretend to care about justice. Or democracy. Or freedom. What . . .’

His wife cast him a vicious look.

‘Wrong time for a lecture, Henk,’ she said quietly.

‘Is it? If Alamy wasn’t in jail for no good reason would we even be here?’

There was an urgent knock on the door. Bakker went to answer it. Koeman was there. She listened and looked at Vos. He got the message and went outside.

‘We got something off that call,’ the detective said. ‘There was the sound of ducks. And trains. When they got it as loud as they could they think there’s an announcement.’ He paused. ‘It’s got to be near a station. We’re guessing Centraal.’

‘A boat,’ Vos said. ‘I knew it was a boat.’

‘You did,’ Koeman agreed. ‘That probably means somewhere around Westerdok. Closest place I can think of. I’ve got uniform down there asking questions.’

‘I want to see,’ Vos said, and glanced at Bakker. ‘Get us a car.’

‘What about this lot?’ she asked looking back at the interview room.

Van der Berg had joined them.

‘Sadly,’ he said, ‘it’s not illegal to be a complete jerk. I think that stuck-up bastard likes to wind us up. Best we don’t give him the pleasure.’

‘They’ve nothing for us,’ Vos added. ‘You saw what it was like in Leidseplein. If there were two, three, more Black Petes looking for a kid in a pink jacket it’s hardly surprising they got confused . . .’

‘The timing!’

‘Westerdok,’ he said. ‘A car.’ A nod at Van der Berg. ‘Three of us.’

‘Also,’ Koeman added, ‘that nice lady from AIVD has been on the line asking how we’re doing. And the mother’s in an interview room wanting to see you. She says it’s important.’

‘Tell Mirjam Fransen we’re still looking. I don’t have time for the mother right now. Keep her happy.’

The detective grimaced.

‘She’s still pissed off with me for giving her a hard time yesterday. Every reason to be.’

‘Buy her a coffee,’ Vos added, patting his shoulder. ‘Make amends. Say you’re sorry. See if she’ll accept some help. She’s a decent woman. No fool.’

Then he returned to the interview room. Kuyper got to his feet. His daughter did the same.

‘Thank you for your time,’ Vos told them. ‘We appreciate it. You can leave now.’

‘I know,’ Henk Kuyper said and led his family out into the corridor, down towards reception and the street outside.

Footsteps in the cabin outside again. Natalya closed her eyes and listened intently. Through the cracks in the timber planking she could see it was starting to get dark. Trains somewhere. People going out, going home.

A few hours earlier he’d come back with more food: a sandwich of strong Dutch cheese, a packet of crisps, a fizzy drink. She’d told the black balaclava she didn’t like fizzy drinks. He’d said nothing, just gone out and got a glass of water from somewhere. Left her little cabin and took a phone call she could just about hear. This was the man who’d given her the book. She felt sure of that. Not the one from the night before.

Bored, more than a little angry, she waited, watching the cabin door. He came in. Same clothes, same black mask to hide his features. But he didn’t put the balaclava on until he was just inside.

She saw something. Saw him.

And maybe he noticed too.

Trying to look stupid she stared at the food as he cleared away the wrappers from the sandwich.

‘I did the sums you gave me.’ She pulled out the colouring book and went to the page she’d done that morning. ‘Don’t you want to check?’

He grunted something about being busy. This one had an accent. Much like the one from the night before. The Black Pete who’d snatched her.

Only two of them, she thought. They took turns, leaving her alone for hours, locked in the tiny bows of a boat somewhere near the station.

‘Are you frightened of me?’ Natalya asked.

He stopped, hands full of rubbish like one of the hunched men she saw on the street, clearing out the bins.

‘Be silent, girl,’ this Black Pete told her. ‘Know your place.’

She cocked her head to one side and looked at him.

‘What place is that?’

He raised his hand. She didn’t flinch. This one was very different.

‘Eight years old, Natalya Bublik. Shut up and be grateful you’re alive.’

The other man had never mentioned her name. Nor asked it. And yet they knew.

She put her head down, picked up the colouring book and a crayon. Drew something on the page.

He didn’t look. Then his phone rang again and he left her, bolting the door behind him.

Natalya found the blank page behind the cover. Drew and drew. And wrote.

First though she remembered the brief conversation she’d heard and thought about what she saw.

Then she turned to the back of the colouring book and in careful writing, in Dutch so someone else would easily understand, set down two lines.

One of them is called Carleed or something. I think he’s a kind of boss.

He’s got dark skin, a big beard, all black and shiny, like a pirate.

Then, her hand shaking at the thought . . .

I think he knows I’ve seen him.

In a small and stuffy interview room in Marnixstraat Hanna Bublik sat with a miserable, embarrassed Koeman. Not saying what she wanted to tell Vos because that was for his ears only. This man was the fool who’d let them down the day before. Eyed her suspiciously as a questionable foreigner when he should have been helping, listening to her pleas.

She ignored the coffee and listened to him trying to justify what he’d done.

‘Can I get you something to eat?’ he asked eventually.

‘I’m not destitute.’

‘I was trying to be polite.’

She scowled and looked at her watch.

‘When will Vos be back?’

‘I don’t know. I can call you when we know something.’

She looked into his sad, bleary eyes.

‘Will they find my Natalya?’

‘Yes,’ he said without conviction.

‘Then I’ll wait.’

There was a commotion outside in the corridor. Through the door she could see the hard-faced woman who wasn’t quite a cop marching purposefully past. She was with the big man who’d been with her the day before in Leidseplein. Hanna understood these people were intelligence or something. They didn’t like the police much. The feeling was reciprocated.

Koeman saw too, and heard. Then muttered a curse under his breath.

In a loud and uncompromising voice Mirjam Fransen was demanding to see Frank de Groot. She didn’t sound happy.

Westerdok ran out from the railway lines into the stretch of water called the IJ. Once a run-down port area it was now in the midst of redevelopment. On the station side stood new hotels, cafes and a modern courthouse to replace the old building on the Prinsengracht, not far from Vos’s home. The adjoining islands housed apartment blocks, industrial buildings, dead warehouses . . . and lines and lines of houseboats along the grey canals.

By the time Vos, Bakker and Van der Berg got there uniform had twenty officers out in the street, knocking on doors, asking questions. Van der Berg parked the car not far from the sparkling new courthouse, looking at the long line of boats that stretched alongside the straight road running north. Fifty or more of them. Uniformed officers were a third of the way along already.

‘Can’t be here,’ Bakker said. ‘It’s too obvious.’

‘True,’ Vos agreed.

This area wasn’t made for cars. The streets were narrow. Sometimes roads ended in nothing more th

an a pedestrian alley or bridge.

He got out, talked to a crew of uniform and relieved them of two bikes.

Van der Berg looked worried. He wasn’t a cycle man. Vos told him to stay near the car, work the radio, keep them up to date. Then he passed a bike to Bakker and the two of them rode to the adjoining islands, working their way into the centre of the quiet, half-residential, half-industrial streets there, just a stone’s throw from the busy city.

After a few minutes they were on the opposite stretch of water to the courthouse, looking at the boats, Vos frowning. There was money coming into Westerdok. This was more a marina than a community made for living. Fancy speedboats, cruisers that could cope with the sea if necessary. Real houseboats never moved. They were wired into the mains, plugged into the phone system, connected to water and drainage. Permanent homes on the water.

‘What are we looking for?’ Bakker asked as they came to a halt next to a fancy yacht with a couple seated by a gas fire in the stern, sipping wine, watching them suspiciously.

‘Something old,’ he said. ‘Like a klipper barge. It never moves.’

He got off the bike and went to the yacht. The man in the back stood up. He was smoking a cigar. Looked fat and comfortable. Didn’t react when Vos showed him his police ID and asked about strangers and barges.

‘We don’t get all that poor shit around here,’ the man said. ‘You need to go . . .’ He gestured to the area east of them. ‘Few of them around there.’

‘Lived in?’ Vos asked.

His big shoulders heaved.

‘I guess. If you want to make money you sell them to the speculators. Rent them out to dumb tourists for fifteen hundred euros a week. Let them bang their head on the roof and deal with all that damp.’

Vos said thanks.

Bakker followed him back to the bikes.

‘If you were going to kidnap someone would you take them home?’ he asked.

‘No. I’d rent a place somewhere.’

‘Quite.’

He called Van der Berg and asked him to get someone in Marnixstraat looking at the web rental sites for any houseboats in the Westerdok area. Then they cycled over the Bickersgracht bridge, into Galgenstraat and started poking around. There were more uniforms working the canal. But the man on the yacht was wrong. Hardly any old houseboats here. And every one of them had checked out.

Ten minutes more fruitless searching. Night had fallen, cloudy and dark. They were pedalling down narrow, ill-lit streets getting nowhere when Van der Berg called back with news. There were seven boats out for short-term rental on the web. Four of them were empty. Two others had been checked already and cleared. The last was in Realengracht to the north.

‘I’ll send someone round,’ Van der Berg said.

‘Don’t bother,’ Vos told him. ‘We’re nearly there.’

Fransen and Thom Geerts had to wait outside De Groot’s office until he was clear of a management meeting elsewhere. That didn’t help their mood. The moment he returned they followed him into the room squawking all the while.

Koeman had accompanied De Groot up from reception, warning him along the way. Updating him on what little they knew of the situation in Westerdok too.

De Groot liked his office. There was a view of the canal from the window and the broad thoroughfare of Elandsgracht down to Vos’s houseboat. It was a place he could think. But not with two intelligence monkeys whining in his ear.

He listened to Fransen’s moans, glanced at Koeman and said, ‘What is this? We’re chasing a lead. That’s all. We don’t have anything of substance. No address. No—’

‘We’ve got a phone call with ducks, trains and a station announcement, for God’s sake,’ Koeman told him. ‘We’re guessing it’s Westerdok. We could be completely wrong. The bastard might have taken the kid out of the city for all we know.’

Fransen sat down. Geerts did the same. He looked as if he mirrored her every move.

‘You need to keep us in the picture,’ she said. ‘This is the second time today Vos has marched off without telling anyone.’

‘What?’ Koeman squealed. ‘We don’t have time to call you every time someone farts around here. What about this Alamy guy? The ransom? What do we do when this bastard calls back tomorrow and gives us a deadline?’

‘There’ll be no ransom,’ Geerts insisted. ‘We told you that already. The Dutch government doesn’t give in to blackmail.’

De Groot waited. That was it.

‘So what do we do?’ he asked.

‘Stall,’ Fransen said. ‘Spin it out for another day. We’re expecting a final court ruling on his appeal tomorrow. Maybe that will change things.’

Koeman scratched his head and asked, ‘How?’

‘Tell him there are problems arranging the plane,’ Geerts suggested, ignoring the question. ‘Get one more day out of him. Then another if we need it.’

‘And in the meantime find him,’ Fransen added. ‘How about that?’

Koeman rolled back his head and said, ‘We’re trying.’

‘Whereabouts are you looking in Westerdok?’ Fransen asked.

‘All over,’ De Groot said. ‘Nothing to report yet. If there is . . .’ He looked at the door. ‘I’ll pass it on.’

‘Do you have anything to tell us?’ Koeman asked them. ‘Any little thing that might help?’

‘If we did you’d know it,’ Fransen told him. She didn’t look ready to move. ‘Where’s Vos? Where exactly?’

Koeman kept quiet. So did the commissaris.

‘Enough,’ Fransen said. She nodded at the detective. ‘Out of here. I need to talk to De Groot alone.’

The narrow old house in the Herenmarkt felt cold. Winter was coming on the night wind, brought in from the chilly waters of the IJ and the sea that fed it.

They ate the food she put on the table: spaghetti carbonara, bought from Marqt around the corner, made with the sauce they provided. Everything in the place came from somewhere, she thought. None of it was made. Was hers.

The pregnancy was an unwanted surprise but when the child turned out to be a daughter she was hopeful. Together they’d be a joint buffer against his forceful, demanding personality. But then Henk stepped in somehow, not long after Saskia was born. Before she could forge a bond between them he was there. Pushing the pram, talking to her, singing to her. Keeping her for his own. Another possession to be put in place for the moment she’d be needed.

He liked everything in order. Filed away. Predictable. So she went down to the organic supermarket with orders about what to buy: the right kind of food, nothing from China, nothing mass-produced. Though it all tasted the same in the end. That pickiness on his part was just another facet of his need to control her.

And criticize. That was important too. Already he’d informed her the Parmesan tasted a little stale. She’d grated it carefully two days before, the last time they ate like this. Kept it in an airtight container. But Henk, with his fine, discerning palate, could taste something old and dry, not that she noticed. So in future she’d have to grate it afresh on every occasion and get the quantities wrong as usual, which meant he could scold her when he found her trying to empty out the unused dregs into the food recycling box without his noticing.

She watched him curl the pasta round his fork and spoon so carefully, with a precision and neatness she could never emulate. Saw that Saskia did the same now. Copied him, always.

Her mind wandered to the Georgian woman again. Hanna Bublik. She’d asked the name at the police station and for some reason the young woman detective Bakker had told her.

What kind of life had she led with her daughter? How did poverty feel? What measure of desperation would drive a woman to sit in one of those glass cabins of a night, trying to entice a stranger to her hard single bed, to service him like a living machine? All for no more euros than she might spend in a single shopping expedition down Marqt making sure Henk got the wine he liked, the cheese he preferred, the right kind of pasta, meat from a guaran

teed organic farm and salad leaves so odd and exotic that she’d no idea what they truly were.

The woman and her child must have lived in a kind of hell. But there were other sorts too.

She looked at Henk and said, ‘How did you find Saskia in Leidseplein? I still don’t understand.’

The girl sighed, looked at her plate of food. Put her knife and fork on the pasta that remained and got up muttering something about going to read in her room.

‘You know,’ he said lazily when she’d left, ‘I long ago accepted I’d never get any thanks for what I do. But ingratitude seems a touch boorish in the circumstances.’

‘There’s a little girl missing. If we can help . . .’

‘It’s called observation,’ he broke in. ‘You should try it.’

‘That’s not fair,’ she muttered. ‘I do my best.’

His hand came out and patted hers.

‘I appreciate that.’

He grabbed the bottle of wine. An organic Amarone. Too heavy for her and he knew it. The glass he filled very precisely, swirling it under his nose before taking a sip.

‘I take it you no longer want to get away,’ he said. ‘If you do the offer’s still open.’

It struck her then: he desired this. Wanted her out of the house. Perhaps never to come back. That way he’d have Saskia forever. The battle would be won for good.

‘I changed my mind. I’ll stay and see this through.’

‘Good,’ he said with no conviction.

‘I saw your father this morning. He’s a kind man, Henk. He doesn’t deserve your hatred. He—’

‘Kind?’

‘That’s what I said.’

His eyes were on her. She could see the drink in them.

‘You always think you know people,’ he said, with a half a slur. ‘You never really do.’

‘Is that me you’re talking about? Or are you just speaking for humanity in general?’

More of the blood-red wine went down.

‘Why do you hate me?’

‘I don’t have the energy for hatred,’ he said with a sudden savage glance. ‘That’s for children. I really think after all this time you might have realized. But . . .’

The Garden of Angels

The Garden of Angels Solstice

Solstice Death in Seville

Death in Seville A Season for the Dead

A Season for the Dead The Killing tk-1

The Killing tk-1 The Savage Shore

The Savage Shore Dante's Numbers

Dante's Numbers Sacred Cut

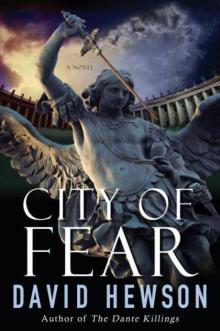

Sacred Cut City of Fear nc-8

City of Fear nc-8 The Blue Demon

The Blue Demon The Garden of Evil

The Garden of Evil The Lizard's Bite

The Lizard's Bite The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Sleep Baby Sleep

Sleep Baby Sleep Lucifer's Shadow

Lucifer's Shadow Season for the Dead

Season for the Dead The Seventh Sacrament

The Seventh Sacrament The Garden of Evil nc-6

The Garden of Evil nc-6 Juliet & Romeo

Juliet & Romeo A Season for the Dead nc-1

A Season for the Dead nc-1 The Fallen Angel nc-9

The Fallen Angel nc-9 Little Sister

Little Sister The Lizard's Bite nc-4

The Lizard's Bite nc-4 The Killing 2

The Killing 2 The Fallen Angel

The Fallen Angel The Sacred Cut

The Sacred Cut Carnival for the Dead

Carnival for the Dead The Villa of Mysteries nc-2

The Villa of Mysteries nc-2 Macbeth

Macbeth The Killing - 01 - The Killing

The Killing - 01 - The Killing The Villa of Mysteries

The Villa of Mysteries Dante's Numbers nc-7

Dante's Numbers nc-7 The Sacred Cut nc-3

The Sacred Cut nc-3 The Seventh Sacrament nc-5

The Seventh Sacrament nc-5